Two weeks ago I wrote about the opening of the

William Kentridge show at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art – and especially the chance to see the artist staging a performance piece called

I Am Not Me, The Horse Is Not Mine in a small theater at the Museum.

SFMOMA also arranged to remount Kentridge's 1998 production of Monteverdi's

Return of Ulysses. I attended the final performance tonight at Project Artaud Theater, a reclaimed industrial building South of Market.

All photos below here were taken by museum staff during set-up and rehearsals.

I ordered this ticket the same day they went on sale, and got sixth row center. I would have bought two, except for not being able to think of anybody who would be available and interested in one of the earliest of Italian operas staged with puppets by an innovative South African best known for his charcoal animations. As it turned out all performances sold out early. These $85 tickets were being scalped this week for $300. A considerable group stood outside the theater at performance time without tickets, hoping somehow to procure them.

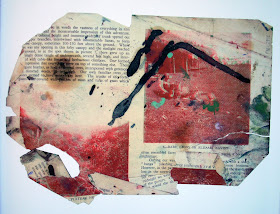

At center on table (above) the Kentridge drawing on the cover of the original 1998 prompt book.

There are two Ulysses puppets (as seen above). The one in the foreground is an old man dying in a Johannesburg hospital. Images representing the inside of his declining body are frequently projected onto the rear screen, and his figure is seldom off the stage. Kentridge credits the medical imagery to the medical textbooks and journals his wife would leave around the house, and it clearly appeals to him that this imagery is accidental and "found" rather than invented. The puppeteer in charge of the dying Ulysses has for long stretches the humble but astonishing task of representing the breathing of the failing figure under the striped sheet. But at the same time the vigorous, prime-of-life Ulysses (as seen at rear against the projected path he will follow to regain Penelope) wears the hospital pajamas and striped hospital sheet transformed into believable garb for a wanderer/warrior. His conquests & triumphs (the upright puppet) and his ultimate mortality (the supine puppet) are seldom out of each other's sight.

Kentridge positions the musicians on a semi-circular stage-frame resembling an operating theater, as the program notes express it ... "thereby solving one of the most difficult logistical questions of early baroque opera: how to maintain the acoustic proximity of the singers and their accompanists." I could wish I had access to more and better pictures of the superb players and their period instruments. Sadly the musical aspect of this musical event is the most difficult to represent in a format like this one. Audioclips wouldn't help much, even if I had them. Nor do I have the rhetorical command of a music critic. The most accurate compliment I can pay is that even though I know this music intimately well, I felt as if I were hearing it for the first time.

The two pictures above give a rough approximation of how beautifully the stage was lighted. They also illustrate how each puppet was consistently supported by two people. The puppeteer had primary responsibility for the puppet, but the singers in every case participated in determining the puppet's gestures, and sang toward the puppet as if channeling their voices through the puppet. The puppeteers had more of a tendency to mirror in expression and stance whatever the puppet was expressing. One unexpected touch on the puppets was the eyes. The heads were carved from some pale wood, not painted or embellished, but the eye sockets deep inside contained reflective and faceted elements that occasionally caught the light and registered as the spirit behind a living face.

Ultimately, the old man's death coincides with the hero's reclaimed marriage bond.

The performance lasted 100 minutes with no intermission. The coherence of the staging and the finesse of Pacific Operaworks instrumentalists created a seamless suspension of time. Kentridge's film and animation effects on the rear screen could have kept me enthralled for 100 minutes with no music or singers or puppets or story at all. But in fact, as Stephen Stubbs writes in the program:

This production achieves the main ambition of opera: to be a Gesamtkunstwerk or artistic whole, an ambition so rarely achieved in practice.