After making dozens of drawings and sketches to prepare himself, Georges Seurat painted Une Baignade, Asnières in 1884. This large summer landscape with figures was rejected by the Paris Salon as incomprehensibly Impressionistic. The artist was 24. Today the picture is a universal object of worship in London at the National Gallery.

In 2004 Michael Craig-Martin made Reconstructing Seurat (Orange) and Reconstructing Seurat (Purple). For this project, Craig-Martin imported the splendid and jarring color-vocabulary of poster-maker Peter Max, a young artist (like Seurat, but eighty years later) who gained fame and fortune instantaneously (instead of scorn) but who is now only remembered as a footnote to the Sixties.

The postmodern rag bag often involves a trick like this, selecting recognizable elements from two distinct art-historic moments and then tossing them together to produce a more-or-less fresh-looking quilt.

Wednesday, July 31, 2013

Mitko

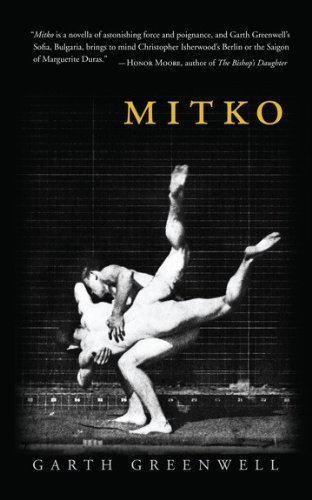

Mitko is a short novel published in 2011 by University of Miami Press (of Oxford, Ohio) – with cover image adapted from a now-famous 19th century stop-motion photograph by Eadweard Muybridge. The setting is Bulgaria, primarily Sofia, where young American author Garth Greenwell (below) was teaching at an elite high school during the time he wrote the book.

Among the back-cover blurbs is one by accomplished fiction writer Margot Livesey who commends Greenwell's "Jamesian skill in parsing emotions . . ."

Here, in the voice of the nameless narrator, is a typical sentence (p. 48): "And so it is, I thought then, as the man and his child released each other and retreated from the water and as I prepared finally to bend my head to my work, so it is that at the very moment we come into full consciousness of ourselves and begin gathering impressions with which to stock that consciousness, developing thereby the habitudes and expectations that will form the personalities we are graced or burdened by, at this very moment what we experience is leave-taking and loss, a pang and a wound that is then inextricable from who we are, a betrayal (if it is a betrayal) the size and the shape of which determine the size and shape of what we ourselves become."

Agreed, this sounds similar to the sinuosities of a Henry James sentence. Yet the story is not put together like a Henry James story at all. Where James imposes plot, Greenwell finds a dim miasma more authentic. It is hard to imagine a Henry James novel set in Bulgaria. Or to imagine Henry James choosing an alcoholic gay street hustler as his title character. But maybe, if such a Henry James novel existed, it would have turned out to be exactly this one.

Tuesday, July 30, 2013

Stubborn Interests

|

| Raymond Roussel, c. 1926 |

"It's true that I've maintained a very continuous, very stubborn interest in the work of people like Roussel and Artaud, or Goya for that matter. But the way in which I question those works isn't entirely traditional. In general, the problem is the following: how is it that a man who is mentally ill or judged as such by society and by contemporary medicine, can write a work that immediately or years, decades, centuries later is recognized as a true work of art and one of the major works of literature or culture? In other words, the question becomes one of knowing how madness or mental illness can become creative.

That's exactly my problem. I never ask myself about the nature of the illness that may have affected men like Raymond Roussel or Antonin Artaud. Nor am I asking about the expressive relationship that might exist between their work and their madness, or how through their work we recognize or rediscover the more or less traditional, more or less codified face of a specific mental illness. Finding out whether Raymond Roussel was an obsessive neurotic or a schizophrenic doesn't interest me. What interests me is the following problem: men like Roussel and Artaud write texts that, even when they gave them to someone to read, whether that person was a critic, or a doctor, or an ordinary reader, are immediately recognized as being related to mental illness. Moreover, they themselves established, at the level of their everyday experience, a very deep, ongoing relationship between their writing and their mental illness. Neither Roussel nor Artaud ever denied that their work evolved within them from a place that was also that of their uniqueness, their particularity, their symptom, their anxiety, and finally, their illness. What astonishes me, what I keep wondering about, is how is it that a work like this, which comes from an individual that society has classified – and consequently excluded – as ill, can function, and function in a way that's absolutely positive, within a culture? We may very well claim that Roussel's work wasn't recognized or invoke Riviere's reticence, discomfort, and refusal in the presence of Artaud's early poems; nonetheless, the work of Roussel and Artaud began to function positively within our culture very, very quickly. It immediately, or almost immediately, became part of our universe of speech. We see, then, that within a given culture, there's always a margin of tolerance for the suspicion that something that is medically treated with suspicion can play a role and assume an importance within our culture, within a culture. It's that positive function of the negative that has never ceased to interest me. I'm not asking about the problem of the relationship between the work and the illness, but the relationship of exclusion and inclusion: the exclusion of the individual, of his gestures, his behavior, his character, of what he is, and the very rapid, and ultimately rather straightforward, inclusion of his language."

– Michel Foucault (1926-1984) from Foucault/Bonnefoy interview transcript of 1968, published for the first time in French in 2011 as Le beau danger: Entretiens avec Claude Bonnefoy. The English translation, Speech Begins After Death only recently appeared from University of Minnesota Press. The bold jacket design was illustrated and extolled here.

|

| Antonin Artaud, 1923 |

Monday, July 29, 2013

Oriental Carpet

|

| Orientalischer Teppich |

Without knowing who made it, I stumbled across this image and singled it out for attention. Then I read some text and discovered that the object of my interest had been assembled by an artist with the familiar-sounding name of Hans-Peter Feldmann.

Checking back, I discovered he appeared here in June, with squares of light and picture hooks.

Orientalischer Teppich (on its plinth, as shown) was his contribution to a recent group show called The Stubborn Life of Things at KAI 10 in Düsseldorf.

Sunday, July 28, 2013

Arcadia

Tom Stoppard's Arcadia, first published in 1993, went through a successful round of productions, starting at London's National Theatre and including a five-month run on Broadway in 1995. Below, Felicity Kendal as Hannah Jarvis during one of the original performances. She created lead roles in a number of new Stoppard plays throughout the eighties and nineties. The run of Arcadia coincided with the beginning of their lives together (at the cost of breaking up both their marriages to other people).

Stoppard sold his archive to the famous Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, where an original, hand-corrected typescript of Arcadia (above) went to rest, among mountains of other documentation. I reproduce it partly because the play concerns itself ardently with the impossibility of adequately reconstructing the past through surviving documents, demonstrating repeatedly that the most crucial documents are in many cases the likeliest to be destroyed. And those that do survive physically must also survive the gradual erosion of context.

Tom Stoppard became famous in 1966 with an absurdist comedy called Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (the title characters extracted from Hamlet). As a teenager, I read Rosencrantz & Guildenstern and thought it was dry and boring. This was because I did not at that time appreciate or even understand the tradition from which the play sprang, the dark modernist European tradition of Kafka, Beckett, Ionesco and their cronies. Stoppard was, in fact, all those years ago, pointing me toward the postmodern future, where signifiers would increasingly wander and shift inside the spaces of plays and novels and poems, but I could not know about that.

Strike two (and a more serious one) against the author was the 1998 movie called Shakespeare in Love (Stoppard shared an Oscar with another writer for the screenplay). That film struck me as fuller of soppy anachronisms than a Swiss cheese is full of holes. Tom Stoppard cemented his place on the long list of writers I had (at some point or another) decided were (for one reason or another) not for me.

But then I looked into Arcadia (another of those books picked up by chance at the library) and was immediately hooked, even against my will. It is a great play. Many people have been saying this since 1993. My freshly-formed opinion had no novelty. But what it did have was an enormous impact on my relationship with Tom Stoppard. All misunderstandings of the past were instantly cancelled out, forgotten, regretted.

Arcadia received its second London production in 2009 (as seen in the three publicity stills below). In the same large schoolroom of an English country house scenes shift back and forth in time between "the past" (a specific period, 1809-12) and "the present" – with the two eras intermingling increasingly as the complex comedy unfolds.

In the London revival of 2009, the author's son, established professional actor Ed Stoppard (at left, immediately above) took the part of Valentine – which sounds to me very much like a character from Congreve. Well-informed critics say Goethe supplied the frame for the play with his novel Elective Affinities, published in 1809 (Stoppard setting the beginning of Arcadia in the same year). That being true, the influence I mostly hear echoing (more in rhythm than vocabulary) is the prodigious banter of Congreve, especially The Way of the World.

A revived Broadway production of Arcadia came two years later. In the four stills (below) from that staging, there is something especially interesting about the costumes. The designer grabbed the opportunity to set "the present" scenes of Arcadia in 1993, "the present" at the time the play came out. That way, the 2011 production could participate in the selective revival of nineties colors and shapes, then in progress in the fashion world at large.

Most recently, Arcadia's revival wave came to San Francisco. The production below appeared at ACT in May and June 2013.

Judging by photos, set designers in San Francisco indulged in their usual over-elaborate prettification. How provincial they make themselves look, compared to New York and London. Curved walls, heavy cornice, preposterous skylight, hand-painted trompe-l'oeil wallpaper, even an elevated patterned floor in the shape of a wide half-circle under the windows. And it's not as if Stoppard didn't explicitly describe the look and function of his imagined Room –

"A room on the garden front of a very large country house in Derbyshire in April 1809. Nowadays, the house would be called a stately home. The upstage wall is mainly tall, shapely, uncurtained windows, one or more of which work as doors. Nothing much need be said or seen of the exterior beyond. ... The room looks bare despite the large table which occupies the centre of it. The table, the straight-backed chairs and, the only other item of furniture, the architect's stand or reading stand, would all be collectable pieces now but here, on an uncarpeted wood floor, they have no more pretension than a schoolroom, which is indeed the main use of the room at this time. What elegance there is, is architectural, and nothing is impressive but the scale."

Saturday, July 27, 2013

Summer Instagrams

Mabel and her parents are out of town visiting friends this week, where there is another little girl to play with plus a new baby. Away from San Francisco Mabel is able to enjoy warm-weather pastimes mostly impossible at home.

Friday, July 26, 2013

Oliver's Embarrassment

The Meaning of Life by Terry Eagleton is a compact little book published by Oxford University Press in 2007. I picked it up at the library by pure chance, where someone had left it on a table with an abandoned stack of other books. What prodded me into actually reading this one was the dedication page – For Oliver, who found the whole idea deeply embarrassing.

"One reason why modernists like Chekhov are so preoccupied with the possibility of meaninglessness is that modernism is old enough to remember a time when there was still meaning in plenty, or at least so the rumour has it. Meaning was around recently enough for Chekhov, Conrad, Kafka, Beckett, and their colleagues to feel stunned and dispirited by its draining away. The typical modernist work of art is still haunted by the memory of an orderly universe, and so is nostalgic enough to feel the eclipse of meaning as an anguish, a scandal, an intolerable deprivation. This is why such works so often turn around a central absence, some cryptic gap or silence which marks the spot through which sense-making has leaked away. One thinks of Chekhov's Moscow in Three Sisters, Conrad's African heart of darkness, Virginia Woolf's blankly enigmatic lighthouse, E.M. Forster's empty Marabar caves, T.S. Eliot's still point of the turning world, the non-encounter at the heart of Joyce's Ulysses, Beckett's Godot, or the nameless crime of Kafka's Joseph K. In this tension between the persisting need for meaning and the gnawing sense of its elusiveness, modernism can be genuinely tragic.

Postmodernism, by contrast, is not really old enough to recall a time when there was truth, meaning, and reality, and treats such fond delusions with the brusque impatience of youth. There is no point in pining for depths that never existed. The fact that they seem to have vanished does not mean that life is superficial, since you can only have surfaces if you have depths to contrast with them. The Meaning of meanings is not a firm foundation but an oppressive illusion. To live without the need for such guarantees is to be free. You can argue that there were indeed once grand narratives (Marxism, for example) which corresponded to something real, but that we are well rid of them; or you can insist that these narratives were nothing but a chimera all along, so that there was never anything to be lost. Either the world is no longer story-shaped, or it never was in the first place."

Thursday, July 25, 2013

Anatolia

Turkish director Nuri Bilge Ceylan (immediately above, photographed by Ebru Ceylan) shared the Grand Prix at Cannes in 2011 for Once Upon a Time in Anatolia. Most worldwide lists included it among the top 10 movies released in 2012. I noticed in the credits that the film was shot in Cinemascope, which I suppose to be a rarely-used, vintage film-format now, but it looked consistently eerie and vibrant in the many lingering, deep-field landscape-shots of the "vast Anatolian plain" – seen by day and by night, in rain and in sun – even though the film's action took place within 24 hours. The landscape was half the story. Muhammet Uzuner may have been the other half, with the leading role of warm-but-troubled-doctor. During one memorable, extended passage, he broke through the invisible "fourth wall" and stared directly into the camera, holding its gaze while doing subtle and mysteriously significant things with his face. In a film paced like this one, such a moment of daring created excitement at the same level as a chase scene.

On the other hand, all women's roles were minor roles. Counting back, I realize there were really only two roles for an individual woman, each in a different plot-segment. And in each case, the woman was beautiful and young and barely had a word to speak, while yet fascinating every man present and stunning them into a silence of their own. In the general absence of women, the male characters told stories to one another, mostly about dead or otherwise absent women. These stories were always about young, beautiful, silent, unpredictable, life-ruining women. Woman as object. Never woman as subject. I'm not sure I altogether believed before that the idealization of women should be read not as flattery but as an expression of their subjugation (a standard olden-days feminist position) – yet this film seemed relentlessly committed to demonstrating exactly how the traditions of idealization and subjugation go together.

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

50 Shades of Grey

"The last quarter-century must rank as one of the nadirs in the history of interior design. The palette of permissible wall colours consists of cool whites and greys. These constitute about 30 per cent of the colours on the Farrow and Ball paint chart, but must account for a far higher proportion of sales. They are currently featuring French Grey (a name coined in the early nineteenth century), and recommend it with a range of like-minded colours – Off-White, Clunch, Lime White, Slipper Satin, Bone, Mouse's Back and Studio Green (which looks charcoaly). That old faithful Magnolia is too warm to exist in our dirty ice age.

After ten years of planning, the new Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam opted for five shades of grey on the gallery walls (one critic christened the shade in the Mondrian room Blu-Tack). A similar range of greys has been deployed in the refurbished European Old Master galleries at the Metropolitan Museum, New York and at Tate Britain.

Design-wise, this is an age of metal and concrete techno-minimalism, with status defined by the sheer volume of forensically lit, textureless, patternless empty space we inhabit. Metal-framed glass walls and doors, blinds and shutters, serried ranks of skylights and halogen downlighters banish sensuality, shape and shadow. When grey first became fashionable in the 1990s it was called gunmetal grey, and it became the neocon colour of choice (along with black), its macho military-industrial connotations echoed in SUVs, Ray-Ban aviator sunglasses and Norman Foster's hi-tech architecture. After the second Iraq war, the term gunmetal mysteriously vanished from the design lexicon (Castle Grey is as militant as F&B get). The American building materials and paint behemoth Sherwin-Williams now offers (among hundreds of greys) the more topical Austere, Conservative, Serious, Uncertain, Techno, Software and – for good/evil measure – Swanky, Wall Street and Dorian Gray. It can't be long before they offer Christian Grey (and Anastasia Steele), named after the sadomasochistic self-made hero of Fifty Shades of Grey."

– from James Hall's review of Paper Palaces : the Topham Collection as a source for British Neo-Classicism (exhibition at Eton College Library) in the TLS, 5 July 2013

After ten years of planning, the new Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam opted for five shades of grey on the gallery walls (one critic christened the shade in the Mondrian room Blu-Tack). A similar range of greys has been deployed in the refurbished European Old Master galleries at the Metropolitan Museum, New York and at Tate Britain.

Design-wise, this is an age of metal and concrete techno-minimalism, with status defined by the sheer volume of forensically lit, textureless, patternless empty space we inhabit. Metal-framed glass walls and doors, blinds and shutters, serried ranks of skylights and halogen downlighters banish sensuality, shape and shadow. When grey first became fashionable in the 1990s it was called gunmetal grey, and it became the neocon colour of choice (along with black), its macho military-industrial connotations echoed in SUVs, Ray-Ban aviator sunglasses and Norman Foster's hi-tech architecture. After the second Iraq war, the term gunmetal mysteriously vanished from the design lexicon (Castle Grey is as militant as F&B get). The American building materials and paint behemoth Sherwin-Williams now offers (among hundreds of greys) the more topical Austere, Conservative, Serious, Uncertain, Techno, Software and – for good/evil measure – Swanky, Wall Street and Dorian Gray. It can't be long before they offer Christian Grey (and Anastasia Steele), named after the sadomasochistic self-made hero of Fifty Shades of Grey."

– from James Hall's review of Paper Palaces : the Topham Collection as a source for British Neo-Classicism (exhibition at Eton College Library) in the TLS, 5 July 2013

Tuesday, July 23, 2013

Zilia Sánchez

Zilia Sánchez was born in Cuba in 1926. Her earliest influences came from avant garde circles in 1950s Havana. Sánchez moved to New York in 1964 and to Puerto Rico in 1972, where she has lived and worked and taught over the past forty years. The blurb for a recent retrospective at Artists Space described her lifelong project – "Alongside the sensual and haptic “queering” of a hard-edged minimalism, her multi-part works bear relation to the temporal and semiotic sequencing of musical notation, as well as to the architecture of tropical modernism."