|

| Anthony Cardon (publisher) M. Deshages and M. d'Egville in the Ballet-Pantomime d'Achille et Deidamie 1804 etching, aquatint British Museum |

|

| Malœuvre fils (publisher) Le Doyen des Zéphirs, ou, Le Roi des Voltigeurs (caricature of French dancer Auguste Vestris) 1815 hand-colored etching British Museum |

"At the end of the eighteenth century, ballet was split between those supporting tours de force and those who believed that "difficulties," as they were called, should be avoided in favor of a more expressive, refined, graceful, and artless style of execution. Though the controversy neared its most intense period in 1800, as early as 1760 Jean-George Noverre (1727-1810) was pleading, in his extremely influential Lettres sur la danse, that his fellow artists renounce entrechats and cabrioles, abandon tours de force, which he considered to be meaningless. Ironically, 1760 was the year of birth of the man whose brilliance would make tours de force de rigueur for audiences and performers. Auguste Vestris (1760-1842) would overwhelm the dance world with his spectacularly athletic technique: his approach to dancing would be emulated by his fellow dancers as they tried to perform increasingly elaborate beats, greater numbers of pirouettes and tours en l'air, and higher leg elevations. The opposition of those seeking abstract dancerly qualities and those demanding feats of athletic virtuosity was the major controversy of the first three decades of the nineteenth century."

– John V. Chapman, from Auguste Vestris and the Expansion of Technique (Dance Research Journal, summer 1987)

|

| Godefroy Engelmann Le Premier Danseur Monsieur Paul in the ballet Clary ca. 1820-30 hand-colored lithograph British Museum |

|

| Paul-André Basset (publisher) Le Grand Ballet de l'Opera par la Troupe Florentine 1820 hand-colored etching British Museum |

|

| Robert Cooper Mlle Hullin 1822 hand-colored etching British Museum |

|

| Henri Monnier Le Corps des Ballets ca. 1828 hand-colored lithograph British Museum |

|

| Joseph Bouvier Marie Taglioni and Signor Guerra in the celebrated ballet L'Ombre 1840 lithograph British Museum |

"By the 1840s women had become the great ballet stars, and ballerinas wore the familiar bell-shaped dress with cap sleeves, low-cut bodice and long skirts. If you look at fashion plates of the period you can see that costumes developed from fashionable dress of the time. Ballerinas also learned the art of dancing on the very tips of their toes, known as pointe work. There were no stiffened pointe shoes, and dancers darned the toes of their slippers to give additional support. The great Romantic ballerinas were idolised throughout Europe. Marie Taglioni (1804-1884) danced in Paris, St Petersburg, London and Italy . . . The popular image of the Romantic ballerina as an otherworldly, ethereal being was portrayed in lithographs showing them poised on flowers, reclining on clouds and floating through the air. Many ballerinas did perform these feats on stage, but with more than a little help from stage technology."

– Victoria & Albert Museum

|

| Anonymous French printmaker Carlotta Gisi in Giselle ca. 1841-50 hand-colored lithograph British Museum |

|

| J. Graf after Numa Blanc Mademoiselle Fanny Cerrito in the ballet Ondine 1843 lithograph British Museum |

"Fanny Cerrito (1817-1909) was one of a cluster of five extraordinary Romantic ballerinas to grace the stages of Europe. While she introduced no innovative techniques, as did Taglioni and Elssler, she enjoyed a spectacular career as a dancer. Born and trained in Naples, Cerrito became the darling of the San Carlo Opera. After conquering the dance audiences in many Italian cities, her success outside the country obtained for her the position of prima ballerina at La Scala when she was only twenty-one years old. . . . Cerrito's vivacious charm and stage presence enhanced her public image in many of the now-forgotten ballets in which she danced. . . . In London, she worked with Perrot and dazzled the public in his ballets, Alma and Ondine. In the latter, which concerned itself with fanciful marine creatures, she herself devised some of its loveliest choreography. Cerrito was so popular in England that the press, changing the accent on her surname, adoringly dubbed her Miss "Cherry Toes."

– Carol Lee, from Ballet in Western Culture (Routledge, 2002)

|

| John Deffett Francis Fanny Elssler leaping ca. 1850 woodcut from unidentified magazine British Museum |

Her step so light – her brow so fair,

She boundeth like a thing of air –

Or fairy in her wanton play –

Or naiad on the moonlight spray.

Like gossamer on wings of light,

She floats before our tranced sight.

Let's gaze no more – nor speak – nor stir –

Lest we fall down and worship her.

– Memoir of Fanny Elssler (1840), quoted in The Philadelphia Dance History Journal

|

| Edgar Degas Les deux danseuses (in rehearsal room) ca. 1877-78 drypoint, aquatint British Museum |

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Dancer Edmée Lescot 1893 lithograph British Museum |

|

| Lovis Corinth Dancers 1895 etching British Museum |

|

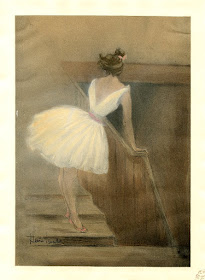

| Henri Boutet Ballerina in the wings 1897 lithograph British Museum |