|

| François Perrier Spinario 1638 etching Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

It is not difficult to imagine 17th-century connoisseurs admiring the ancient statues etched by François Perrier (appearing here yesterday and today). What is difficult to imagine is that for more than three hundred years the same small group of sculptures that appeared in Perrier's collection enjoyed much higher levels of general prestige than any work of the Renaissance, including the Mona Lisa, the Sistine Ceiling, Botticelli's Venus, and Michelangelo's David. None of those named masterpieces, at the pinnacle of prestige today, ascended so high until the middle of the 19th century. And their reputations did not ascend until after the places at the top had been vacated, when virtually all these statues simultaneously fell from grace. People were mainly shocked and disappointed by the discovery that these were, in almost every case, copies rather than originals. The contrivances of the restorers somehow seemed far less disturbing, perhaps because that category of interference did not touch the imagined soul of the work, as questions of authenticity did.

"The emphasis on absent originals was widespread in archaeological writing of the second half of the nineteenth century. Indeed, for the serious traveler who relied on Friedrich's Bausteine or Helbig's Fuhrer rather than Burckhardt's Cicerone or Hare's Walks, the antiques to be seen in the Vatican (or the Uffizi or Naples) were themselves mostly inferior copies, and the distinction in the mind of such a traveler between the Belvedere and a cast gallery was no longer as great as it had been – the more so as among these casts, a number, bronzed, and with their supports removed, were held to give a better idea of the Greek originals than the statues to be seen in Italy."

|

| François Perrier Centaur with Cupid 1638 etching Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

|

| François Perrier Centaur with Cupid 1638 etching Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

|

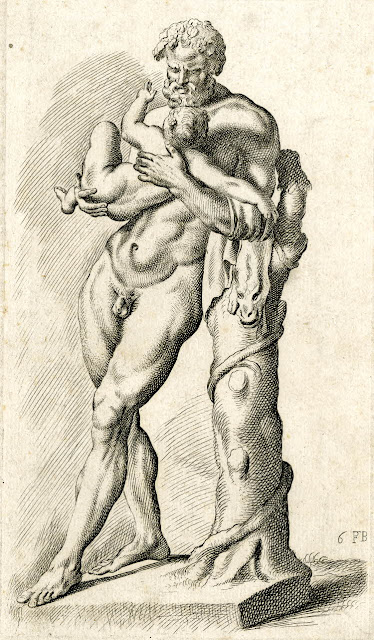

| François Perrier Silenus with the Infant Bacchus 1638 etching British Museum |

|

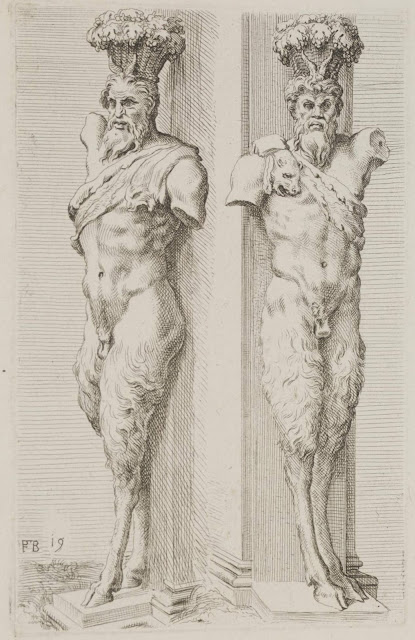

| François Perrier Della Valle Satyrs 1638 etching Victoria & Albert Museum |

The Della Valle Satyrs (above) appear in a drawing of the late 1400s, when they were installed as palace courtyard ornaments between arches. There they remained for many years, apparently unrestored (as Perrier represented them). In 1733 they were part of a large group of ancient sculptures sold to Pope Clement XII (and destined for his new museum, eventually transformed into the Capitoline Museum, where they remain today). But before being delivered to the Pope, they were supplied with identical sets of large ungainly arms, one reaching up to the basket on the head, the other hanging down and dangling a bunch of grapes.

Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny in Taste and the Antique (Yale University Press, 1981) also reproduce an etching from 1594 illustrating the Medici Wrestlers (below) shortly after excavation, and establishing that the group, as discovered, possessed no heads, no arms, and only stumps for legs. By the 1630s when Perrier was making his etchings, all these missing pieces had been supplied. There followed two hundred years of intense writing about the "plainely stupendious" interplay of the limbs ("considered to be of great academic value") and the subtle expressions of the faces. This same pattern was repeated frequently with other antique statues in Rome – well-documented and not-at-all secret restorations immediately became incorporated into the "antiquity" of the original fragment. The supposed mystical qualities of the antique could then also legitimately be discovered in the parts, even if those parts had in fact only been carved yesterday by a living Italian craftsperson, usually anonymous.

|

| François Perrier Medici Wrestlers 1638 etching Philadelphia Museum of Art |

|

| François Perrier Medici Wrestlers 1638 etching Philadelphia Museum of Art |

|

| François Perrier Figure from the Niobe Group 1638 etching Philadelphia Museum of Art |

|

| François Perrier Dying Gaul statue 1638 etching British Museum |

Over the course of the 19th century fashions in art-appreciation and art-collecting changed enough that making physical additions to ancient sculpture in the name of restoration became taboo. "In 1809 Edward Daniel Clarke wrote with pride that the fragment of a colossal Greek statue of Ceres which he had placed in the vestibule of the University Library at Cambridge (it is now in the Fitzwilliam Museum as a Caryatid) would not be 'degraded by spurious additions', and he contrasted his attitude with that which prevailed in France – where indeed, only the year before, Vivant Denon had ordered the sculptor Cartellier to convert an antique torso ('a fragment of the most beautiful work but insignificant in its present condition') into a statue of Napoleon. At exactly the same time in the Specimens published by the Society of Dilettanti, sculpture was illustrated either without modern additions and repairs or with dotted lines to indicate where they were. Lord Elgin originally hoped that his marbles from the Parthenon would be restored, but both he and the British Museum which acquired them in 1818 were dissuaded from this course by Flaxman and Canova, though the fragments that reached the Louvre were in fact repaired."

The etchings and drawings by François Perrier that follow below were not part of his great book of statues from 1638. They show him instead at work exploiting the antique models to which he gave so much direct documentary attention.

|

| François Perrier Time Clipping Cupid's Wings 1632-33 etching - from two superimposed plates British Museum |

|

| François Perrier Diana in her Chariot 17th century drawing Morgan Library, New York |

|

| attributed to François Perrier Tritons carrying off Nereids 17th century drawing Metropolitan Museum of Art |

The final two etchings are from Perrier's 1645 follow-up volume, illustrating his selection of the most beautiful antique relief-work to be found in Rome.

|

| François Perrier Roman Relief : Mounted Hunting Scene 1645 etching Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| François Perrier Captives : from a Relief on the Arch of Constantine 1645 etching Metropolitan Museum of Art |