|

| Anonymous French printmaker The Two are but One (Les deux ne font qu'un) Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette as double-headed beast ca. 1791 hand-colored etching Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

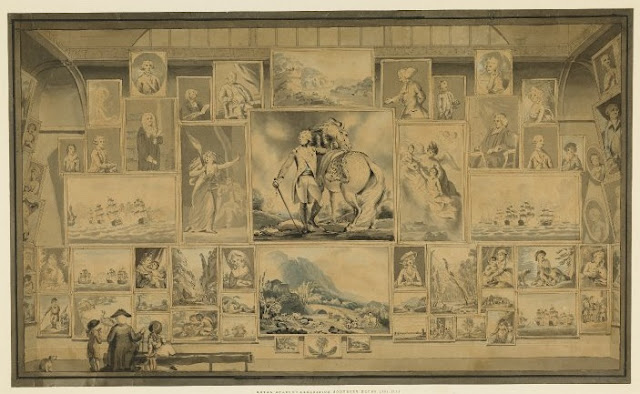

| Thomas Rowlandson Tis Not Antiques Alone Can Please the Eye, or, Tastes Differ (Sir William and Lady Hamilton) 1786 hand-colored etching Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Thomas Rowlandson Admiral Nelson recreating with his Brave Tars after the glorious Battle of the Nile 1798 hand-colored etching and aquatint Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

from Dirge for a Dead Admiral

If, on this winter night,

O thou great admiral

That in thy sombre pall

Liest upon the land,

Thy soul should take his flight

And leave the frozen sand,

And yearn above the surge,

Think'st thou that any dirge,

Grief inarticulate

From thy bereaved mate,

Would answer to thy soul

Where the waste waters roll?

– Samuel McCoy (1913)

|

| Thomas Rowlandson A Couple of Antiques, or, My Aunt and My Uncle 1807 hand-colored etching Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Anonymous printmaker The Flying Philosopher ca. 1800 hand-colored etching Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| James Gillray A Phantasmagoria (political cartoon) Scene Conjuring up an Armed Skeleton 1803 hand-colored etching Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Hieronymus Hess Prison du Château de Chillon ca. 1820-40 hand-colored aquatint British Museum |

|

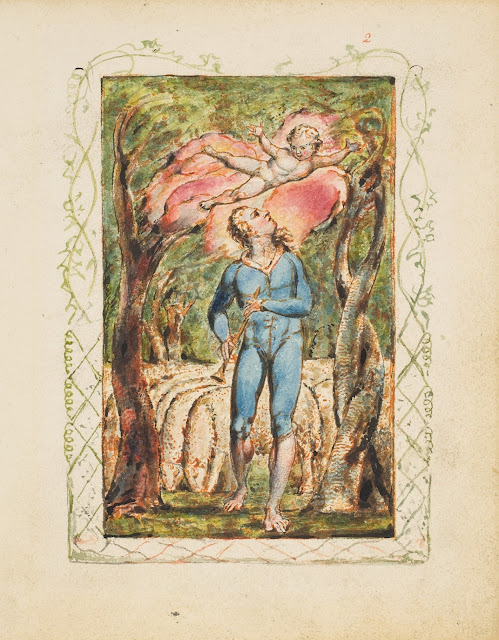

| William Blake Songs of Innocence (frontispiece) ca. 1825 hand-colored etching Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Adam Friedel after Correggio Leda bathing with Swan before 1837 hand-colored lithograph British Museum |

|

| Anonymous printmaker Night View of the Colosseum, Rome ca. 1840-50 hand-colored lithograph (transparency) British Museum |

|

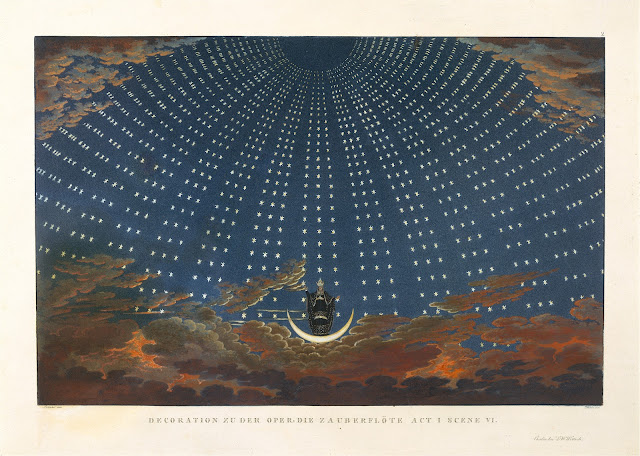

| Karl Friedrich Schinkel Stage Design for Mozart's Magic Flute Hall of Stars in the Palace of the Queen of the Night 1847-49 hand-colored aquatint Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

from Giving a Manicure

The woman across from me looks so familiar,

but when I turn, her look glances off. At the last

subway stop we rise. I know her, she gives manicures

at Vogue Nails. She has held my hands between hers

several times. She bows and smiles. There the women

wear white smocks like technicians, and plastic tags

with their Christian names. Susan. No, not Susan,

whose hair is cropped short, who is short and stocky.

This older lady does my hands while classical music,

often Mozart, plays. People passing by outside are

doubled in the wall mirror. Two of everyone walk

forward, backward, vanish at the edge of the shop.

– Minnie Bruce Pratt (2003)

|

| Anonymous Russian printmaker Cabin interior with family 1882 hand-colored lithograph British Museum |

|

| Paul Gauguin Auti te Pape (Women at the river) 1893-94 hand-colored woodcut British Museum |

– poems from the archives of Poetry (Chicago)