|

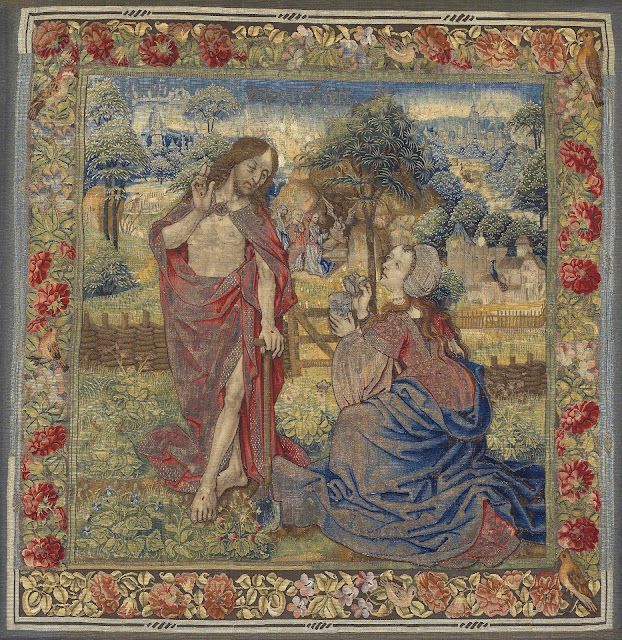

| Unknown Workshop in Flanders Noli me tangere ca. 1485-1500 wool and silk tapestry Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Unknown Workshop in Flanders Bear Hunt and Falconry (fragment) ca. 1525 wool and silk tapestry Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Unknown Workshop in Flanders Pomona surprised by Vertumnus and other Suitors ca. 1535-40 wool and silk tapestry Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Manufacture Royale d'Aubusson Apollo exposing Mars and Venus to the Ridicule of the Olympians ca. 1650 wool and silk tapestry Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Unknown Workshop in Flanders Meeting of Jacob and Rebecca, and Isaac blessing Jacob ca. 1660 wool and silk tapestry Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Michiel Coxie (designer) Diversion of the Euphrates (from The Story of Cyrus) ca. 1670 wool and silk tapestry, woven in Brussels Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Michiel Coxie (designer) Cyrus defeats Spargapises (from The Story of Cyrus) ca. 1670 wool and silk tapestry, woven in Brussels Art Institute of Chicago |

"The word tapestry is now widely used to describe a range of textiles, including needlepoint and certain mechanically woven, ribbed fabrics, but historically and technically it designates a figurative weft-faced textile woven by hand on a loom. In European practice, the loom consists of two rollers, between which plain warp threads (the load-bearing threads) are stretched. . . . Depending on the orientation of the loom, the warps are stretched vertically on a high-warp loom or horizontally on a low-warp loom; in both cases, the weaver works on the reverse side of the tapestry. The warps are arranged so there is a small space between the even and odd warps, called the shed, through which the weaver passes the colored weft threads that are wrapped around a handheld shuttle . . . By varying the colors of the weft, the weaver creates a pattern or figurative image. Between 1400 and 1530, Flemish weavers developed the ability to reproduce an extraordinary range of surface textures and painterly effects through the use of finer and finer interlocking triangles of color (hatchings or hachures), the juxtaposition of different materials, and the use of different techniques to link the weft threads."

"In European medieval and Renaissance practice, the design was invariably copied from a full-scale colored pattern, known as the cartoon, a practice that continues to this day. Before starting work, the weaver traces the pattern from the cartoon onto the bare warps. . . . Production was a labor-intensive process requiring the participation of many skilled weavers for the execution of large tapestries. On the basis of both modern practice and documented production, it is generally estimated that weavers could produce up to one square yard of coarse tapestry per month. High quality production, with a finer warp and weft count, was much slower, yielding perhaps half a square yard or less per month."

"The quality of a tapestry depends mainly on four variable factors: the quality of the cartoon from which it is copied; the skill of the weavers at translating the design into woven form; the fineness of the weave (the number of warps per centimeter and the grade of the weft, which directly affect the precision of detail and the pictorial quality of the tapestry); and the quality of the materials from which it is made. . . . Wool, generally from England or Spain, was the principal material used for warps and most of the weft. Finer-quality pieces also incorporated silk (from Italy or Spain), and the finest included silver- and gilt-metal-wrapped silk thread (from Venice or Cyprus). Documents relating to the levy charged for different grades of tapestry imported to England during the first half of the sixteenth century indicate that tapestry woven with silk cost four times more than that woven with coarse wool. The inclusion of metallic thread increased the cost by a factor of twenty over tapestry woven with coarse wool alone."

– from an essay by Thomas P. Campbell on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

|

| Charles Le Brun (designer) The Offering of the Boar's Head (from The Story of Meleager and Atalanta) ca. 1673-86 wool and silk tapestry, woven in Brussels Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| David Teniers III (designer) September and October (from The Twelve Months of the Year) after 1675 wool and silk tapestry, woven in Brussels Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Lodewijk van Schoor and Pieter Spierinckx (designers) Abundantia (from The Four Continents and Related Allegories) ca. 1680-1700 wool and silk tapestry, woven in Brussels Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Unknown Workshop in Flanders Orpheus playing the Lyre to Hades and Persephone ca. 1685 wool and silk tapestry Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Charles Le Brun (designer) Autumn (from The Seasons) ca. 1700-1720 wool and silk tapestry Manufacture Royale des Gobelins Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Charles Le Brun (designer) Winter (from The Seasons) ca. 1700-1720 wool and silk tapestry Manufacture Royale des Gobelins Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Manufacture Royale d'Aubusson Arrival of Telemachus on Calypso's Island (after an engraving by François Boucher) 1776 wool and silk tapestry Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Manufacture Royale d'Aubusson Fall of Phaeton (after an etching by Antonio Tempesta) 1776 wool and silk tapestry Art Institute of Chicago |