|

| Joseph Heintz the Younger Holy House of Loreto removed by Angels from the Holy Land ca. 1650 etching British Museum |

Monday

First all belief is paradise. So pliable a medium. A time not very long. A transparency caused. A conveyance of rupture. A subtle transport. Scant and rare. Deep in the opulent morning, blissful regions, hard and slender. Scarce and scant. Quotidian and temperate. Begin afresh in the realms of the atmosphere, that encompass the solid earth, the terraqueous globe that soars and sings, elevated and flimsy. Bright and hot. Flesh and hue. Our skies are inventions, durations, discoveries, quotas, forgeries, fine and grand. Fine and grand. Fresh and bright. Heavenly and bright. The day pours out space, a light red roominess, bright and fresh. Bright and oft. Bright and fresh. Sparkling and wet. Clamour and tint. We range the spacious fields, a battlement trick and fast. Bright and silver. Ribbons and failings. To and fro. Fine and grand. The sky is complicated and flawed and we're up there in it, floating near the apricot frill, the bias swoop, near the sullen bloated part that dissolves to silver the next instant bronze but nothing that meaningful, a breach of greeny-blue, a syllable, we're all across the swathe of fleece laid out, the fraying rope, the copper beech behind the aluminum catalpa that has saved the entire spring for this flight, the tops of these a part of the sky, the light wind flipping up the white undersides of leaves, heaven afresh, the brushed part behind, the tumbling. So to the heavenly rustling. Just stiff with ambition we range the spacious trees in earnest desire sure and dear. Brisk and west. Streaky and massed. Changing and appearing. First and last. This was made from Europe, formed from Europe, rant and roar. Fine and grand. Fresh and bright. Crested and turbid. Silver and bright. This was spoken as it came to us, to celebrate and tint, distinct and designed. Sure and dear. Fully designed. Dear afresh. So free to the showing. What we praise we believe, we fully believe. Very fine. Belief thin and pure and clear to the title. Very beautiful. Belief lovely and elegant and fair for the footing. Very brisk. Belief lively and quick and strong by the bursting. Very bright. Belief clear and witty and famous in impulse. Very stormy. Belief violent and open and raging from privation. Very fine. Belief intransigent after pursuit. Very hot. Belief lustful and eager and curious before beauty. Very bright. Belief intending afresh. So calmly and clearly. Just stiff with leaf sure and dear and appearing and last. With lust clear and scarce and appearing and last and afresh.

– Lisa Robertson (2001)

|

| Anonymous French printmaker Grotto at Versailles with statue groups 1676 engraving Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum |

|

| Monogrammist HT Tailpiece from printed book, De Privilegio Rusticorum, Paris 1606 woodcut Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Martin Fréminet A King of Judah and Israel (design for Fontainebleau ceiling) ca. 1605 drawing Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Palma Giovane Samson and Delilah ca. 1611 etching Philadelphia Museum of Art |

|

| Palma Giovane Tutelary Goddess of the City of Rome 1611 etching National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa |

|

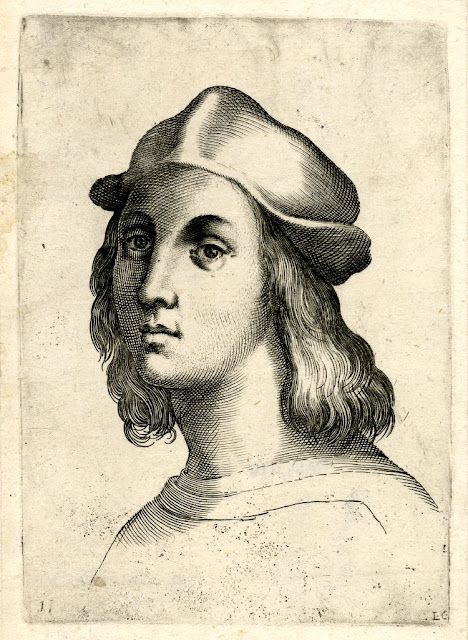

| Luca Ciamberlano after Agostino Carracci Drawing Book Pattern Print - after Raphael Self Portrait ca. 1600-1630 engraving British Museum |

from An Essay on Criticism

But see! each Muse, in Leo's golden days,

Starts from her trance, and trims her wither'd bays!

Rome's ancient genius, o'er its ruins spread,

Shakes off the dust, and rears his rev'rend head!

Then sculpture and her sister-arts revive;

Stones leap'd to form, and rocks began to live;

With sweeter notes each rising temple rung;

A Raphael painted, and a Vida sung.

– Alexander Pope (1711)

|

| Anthony van Dyck Studies of Portrait Medals before 1641 drawing Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

| Anthony van Dyck Portrait of artist Justus Sustermans plate cut 1630-32, printed 1645-46 etching Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

| Anthony van Dyck Portrait of artist Jan Brueghel the Elder plate cut 1630-32, printed 1645-46 etching Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

| Adriaen van de Velde Youth seated on the ground ca. 1646-72 drawing Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

| Adriaen van de Velde Standing youth in armor ca. 1646-72 drawing Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

| Adriaen van de Velde Two studies of a shepherd resting ca. 1666-71 drawing Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

| Gesina ter Borch Fashionable young woman standing with Death at open grave in St Michael's Church ca. 1671 drawing with watercolor Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

Death

Death is a funny thing. Most people are afraid of it, and yet

they don't even know what it is.

Perhaps we can clear this up.

What is death?

Death is it. That's it. Finished. "Finito." Over and out. No

more.

Death is many different things to many different people. I

think it is safe to say, however, that most people don't like it.

Why?

Because they are afraid of it.

Why are they afraid of it?

Because they don't understand it.

I think the best way to try to understand death is to

think about it a lot. Try to come to terms with it. Try to really

understand it. Give it a chance!

Sometimes it helps if we try to visualize things.

Try to visualize, for example, someone sneaking up behind

your back and hitting you over the head with a giant hammer.

Some people prefer to think of death as a more spiritual

thing. Where the soul somehow separates itself from the mess

and goes on living forever somewhere else. Heaven and hell being

the most traditional choices.

Death has a very black reputation but, actually, to die is a

perfectly normal thing to do.

And it's so wholesome: being a very important part of

nature's big picture. Trees die, don't they? And flowers?

I think it's always nice to know that you are not alone. Even

in death.

Let's think about ants for a minute. Millions of ants die

every day, and do we care? No. And I'm sure that ants feel the

same way about us.

But suppose – just suppose – that we didn't have to die.

That wouldn't be so great either. If a 90-year-old man can hardly

stand up, can you imagine what it would be like to be 500 years

old?

Another comforting thought about death is that 80 years or

so after you die nobody who knew you will still be alive to miss

you.

And after you're dead, you won't even know it.

– Joe Brainard (died in 1994)

Poems from the archives of Poetry (Chicago)