|

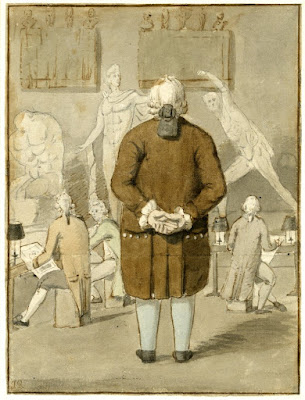

| John Hamilton Mortimer Self-Portrait with Joseph Wilton and a Student ca. 1765 oil on canvas Royal Academy of Arts, London |

"The painting, formerly dated c. 1778-79, has been redated to c. 1765 by John Sunderland who has suggested that it recalls earlier times when Mortimer and the sculptor Joseph Wilton were associated with the Academy attached to the Duke of Richmond's Cast Gallery of 1758-62. This gallery complemented the teaching offered by William Shipley's Drawing School, 1753-68, and the second St Martin's Lane Academy, 1753-68. In 1758 Wilton was made Director of the Duke of Richmond's Academy, and Giovanni Battista Cipriani was in charge of instruction in painting. John Hamilton Mortimer was among the students. The three figures in Mortimer's paintings are Wilton (supervising), Mortimer (drawing after the Antique), and a young student (holding an antique head)."

|

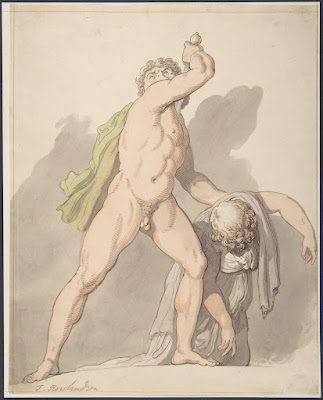

| John Hamilton Mortimer Study of a Cast of the Bacchus of Sansovino ca. 1760 drawing Tate Britain |

|

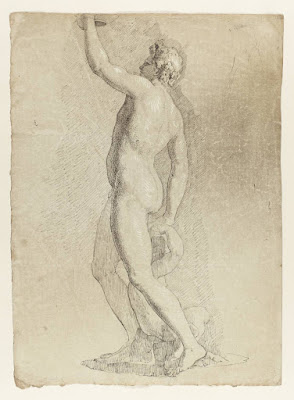

| John Hamilton Mortimer Reclining Model ca. 1773 drawing Yale Center for British Art |

|

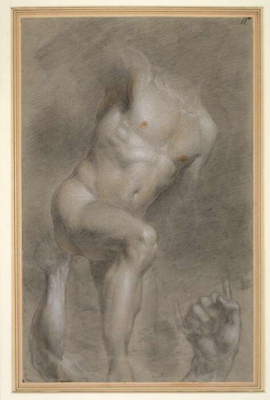

| John Hamilton Mortimer Reclining Model ca. 1757-59 drawing Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

"John Hamilton Mortimer was one of the most precocious draughtsmen of his generation. While a pupil of Robert Edge Pine he studied at St Martin's Lane Academy and at the Duke of Richmond's Sculpture Gallery, winning prizes both for life drawing and for a drawing from a cast of Michelangelo's Bacchus. The medium used by Mortimer in [the drawing directly above], black chalk on grey paper, and the technique, with firm cross-hatching, is very close to that which the artist employed in drawings from the Antique. Nonetheless, although the drawing exhibits Mortimer's control of line and his confident manipulation of tone, it also reveals the difficulties he experienced in coping with the unexpected irregularities of the human form as opposed to the familiar contours of the classical cast – especially in the handling of the area around the upper torso and neck."

|

| John Constable Figure from Michelangelo's Last Judgment ca. 1830 oil on canvas National Trust, Anglesey Abbey, Cambridge |

|

| John Constable Model posed after Michelangelo's Jonah from the Sistine Ceiling ca. 1800-1801 drawing Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

"This work demonstrates the manner in which living models were posed at the Royal Academy to resemble figures taken from the Old Masters, as well as from antique statuary. Here the male model takes up an attitude based on the prophet Jonah from Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling, a practice which Constable, as a Visitor in the Life Schools in the 1830s, favoured when he posed two male figures based on Michelangelo's Last Judgment, as well as a setting based on Titian's St Peter Martyr. . . . On the basis of the paucity of drawings by him from the antique, it has been argued that Constable spent very little time drawing from the Antique. C.R. Leslie noted: 'I have seen no studies made by Constable at the Academy from the antique, but many chalk drawings and oil paintings from the living model, all of which have great breadth of light and shade, though they are sometimes defective in outline.' Graham Reynolds pointed out that this drawing, which shows a lack of confidence in the handling, conforms with Leslie's description."

|

| Richard Cosway Emma Hamilton in Classical Attitude ca. 1800 drawing National Portrait Gallery, London |

"At the time of Cosway's drawing, Emma Hart (1765?-1815) was already famous for the 'Attitudes' she performed after classical statuary during her sojourn in Italy as the mistress of Sir William Hamilton, the British Ambassador in Naples. The first record of Emma's 'Attitudes' was in 1787 when Goethe, who was at the time a guest at Sir William Hamilton's residence, noted: 'He has had a Greek costume made for her which becomes her extremely. Dressed in this, she lets down her hair and, with a few shawls, gives so much variety to her poses, gestures, expressions, etc., that the spectator can hardly believe his eyes . . . The old knight (Hamilton) idolises her and is quite enthusiastic about everything she does. In her he has found all the antiquities, all the profiles of Sicilian coins, even the Apollo Belvedere.' In 1794 Frederick Rehberg produced a series of line engravings of Emma's 'Attitudes' entitled Drawings Faithfully Copied from Nature at Naples. In 1800 she returned to England, around which time Cosway produced this drawing. By this time she was, according to one contemporary, 'colossal, but, excepting her feet, which are hideous, well shaped. Her bones are large, and she is exceedingly embonpoint. She resembles the bust of Ariadne . . ."

|

| Benjamin Robert Haydon Seated Model posed as Hercules 1806 drawing Yale Center for British Art |

|

| George Romney Model posed as Wounded Achilles ca. 1775 drawing Yale Center for British Art |

|

| Robert Ker Porter Model posed at the Royal Academy ca. 1794-95 drawing British Museum |

|

| George Michael Moser Seated Model ca. 1745-50 drawing Royal Academy of Arts, London |

"Although George Michael Moser was active in the Life Class throughout his career, few of his own life drawings survive. As Moser is not known to have worked either in Paris or Rome, it is probable that this drawing was made in London in the St Martin's Lane Academy, possibly in the the 1740s. . . . Moser was known for his abilities as a draughtsman; George Vertue, writing in 1745 about the St Martin's Lane Academy, noted that 'amongst the best Mr. Moser the Chaser has distinguisht him self by his skill in drawing in ye Academy from the life this Winter.' Moser's early history is obscure. He is said to have studied in Geneva before coming to England as a youth to work as a gold- and silver-chaser. Moser also worked as an enameller, medallist, and sculptor. . . . [He was] instrumental in the foundation of the Royal Academy of Arts, and became its first Keeper in 1769. In that post, it was his responsibility to oversee the running of the 'Academy of the Living Model' and the 'Plaister Academy,' including the provision of models, the setting out of casts, and the admission of new students to the Schools."

|

| George Michael Moser after Guido Reni Hercules and the Hydra before 1783 oil on canvas Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Thomas Rowlandson Venus, Anchises and Cupid before 1827 drawing, with watercolor Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Thomas Rowlandson Modern Pygmalion with Galatea ca. 1790-1810 etching British Museum |

|

| Thomas Rowlandson The Sculptor ca. 1800 hand-colored etching British Museum |

"Although Rowlandson's print of The Sculptor was not produced until c. 1800, the clay modello on which Nollekens is shown at work, Venus chiding Cupid, was apparently exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1778. Even though Rowlandson's print is essentially a satirical flight of fancy, the image anticipates the recollections of Nollekens's pupil, J.T. Smith, concerning the sculptor's primary interest in the studio, rather than the academy, model. According to Smith, 'his naked figures were of the most simple class, being either a young Bacchus, a Diana, or a Venus, with limbs sleek, plump, and round; but I never knew him like Banks to attempt the grandeur of a Jupiter, or even the strength of a gladiator."

– quoted passages from The Artist's Model: its Role in British Art from Lely to Etty by Ilaria Bignamini and Martin Postle (exhibition catalogue, Nottingham University Art Gallery, 1991)