|

| Peter Lely Sleeping Nymphs by a Fountain ca. 1650-55 oil on canvas Dulwich Picture Gallery, London |

"From the Renaissance onwards, the standard curriculum of the artist's training in Western countries revolved around three principle subjects: the Antique, the living model and the study of anatomy. Subjects such as technique, ornament, perspective, history and theory also played a crucial role in particular periods and contexts, but the Antique, the living model and anatomy always held a special position. They were taught by masters in their workshops and studios, and from the sixteenth century, at academies of art. . . . The first English academy for which documentation has survived originated in Peter Lely's studio in London, c. 1673, and was probably attended by William Gandy [whose portrait of Dr. John Patch displaying a dissected arm is at the bottom of this post], his friend William Fever, the Irish Catholic portrait-painter Garret Morphey and John Greenhill. George Freeman, a history and scene painter who practised as a drawing-master from about 1663, possibly was in charge of teaching, though it was Sir Peter Lely, then the foremost artist active in England, who supervised drawings executed by students there."

"Many elements converge in Lely's Sleeping Nymphs by a Fountain: the Antique, Old Masters, and the study of the living model. . . . Sir Oliver Millar has drawn attention to the influence of Anthony van Dyck's paintings, such as Cupid and Psyche, which was in Lely's collection in 1660. Malcolm Rogers suggested that the sleeping nymph at the back echoes in reverse the sleeping Ariadne in Titian's Andrians (Prado, Madrid), possibly known by Lely in the reverse engraving by G.A. Podesta. Other sources may be mentioned. A nymph sleeping by a fountain or spring is a figure found in classical sculpture. The nymph to the left in Lely's painting is reminiscent of a Roman statue of the 2nd century A.D., which the nymph to the right resembles the sleeping Hermaphrodite, a type particularly influential in the 17th century and well known to Flemish artists like Rubens and English virtuosi like John Evelyn, who purchased a small ivory copy by François Duquesnoy while in Rome in the late 1640s. . . . Paintings such as Sleeping Nymphs [also] testify to Lely's use of the nude female model in his studio. Moreover, written documents and visual evidence suggest that Lely supervised drawings after the living model, both male and female, executed by students who attended the Academy of c. 1673."

|

| Rembrandt Model posed as the Goddess Diana ca. 1630-31 drawing (print study) British Museum |

|

| Rembrandt Artist in Studio drawing Model on Dais 1639 drawing British Museum |

|

| Rembrandt Nude Woman seated on a Stool ca. 1654-56 drawing Art Institute of Chicago |

"The evident distaste for a naturalistic depiction of the figure was especially manifest by the second half of the eighteenth century, in attitudes towards the female form. While Benjamin West's Eve was promoted as an ideal, Rembrandt's prosaic treatment of the female nude was universally condemned in both France and England. In 1752 an English translation of Edmé-François Gersaint's catalogue of Rembrandt's etchings appeared in English. The introduction stated: 'whenever he introduces a naked figure in to his Compositions he becomes intolerable – the ill Attitudes and Disproportion of his figures, especially of his women, render them extremely disgusting to a Person of True Taste.' And while John Opie told students at the Royal Academy that were it not for the example of the Greeks, 'we might have preferred . . . the rank and vulgar redundance of a Flemish or Dutch female,' Benjamin Robert Haydon believed Rembrandt 'in the naked form, male and female, was an Esquimeaux. His notions of the delicate form of women would have frightened an Arctic bear.'"

"The female model presented high-minded artists at the Royal Academy with several problems. First, as there was no established precedent for the use of the female model in European academies, there was no theoretical basis for instruction. Secondly, unlike male classical statuary, which had been perennially classified and quantified, female physical perfection, as embodied in statues such as the Venus de' Medici, was far more subjectively considered. Finally, the low social status of female models was gravely at odds with the aura which surrounded their mythological counterparts. Male models, chosen principally for their musculature and physique, were often pugilists or soldiers. As such they were respected as individuals whose athletic appearance echoed the classical heroes with whom they were compared. Female models, by way of contrast, were regarded with curiosity and suspicion, especially as many were also prostitutes."

|

| Godfrey Kneller Self Portrait ca. 1670 oil on canvas private collection |

"Painted when Kneller was in his mid-twenties, this Self Portrait shows a young man seated at a table. . . . The objects on the table – the bust, the ecorche figure, and the engraving of a female nude – refer to the three central aspects of academic education, namely the Antique, anatomy, and the study of the living model. The bust has been described as Seneca. The écorché can be identified as the Écorché posed as an archer of which four bronze versions are known. . . . The draughtsman is copying the engraving, which acts as a substitute for the living model. Engravings were, of course, extremely important in art education. Moreover, from the beginning of the 17th century, drawing books were published in most European countries, including Holland. These copy-books or 'printed academies' had the function of substitutes or complements to actual educational institutions. Although the female model depicted here is akin to Venus, her pose is ultimately derived from an antique-type of Apollo standing with one arm over his head."

"Kneller's Self Portrait was probably painted in Amsterdam, where the artist trained under Ferdinand Bol. Subsequently, in 1672-75, Kneller visited Flanders and Italy. He settled in London in 1676, was Principal Painter to the King from 1688, and the first Governor of the Academy established in Great Queen Street, London, in 1711."

|

| Godfrey Kneller Study of Model ca. 1710 drawing British Museum |

|

| Godfrey Kneller Study of Model ca. 1711 drawing British Museum |

|

| Louis Chéron Study of Seated Model ca. 1676-77 drawing British Museum |

|

| Louis Chéron Study of Model posed as Artist ca. 1711-12 drawing British Museum |

|

| Louis Chéron Study of Female Model ca. 1720-24 drawing British Museum |

"Louis Chéron more than any other artist of the period was responsible for insisting on rigorous academy studies. He was a history painter and designer who was trained at the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris and at the French Academy in Rome before settling in England in 1695. Vertue wrote that Chéron 'was much immitated by the Young people' who attended the Academy in Great Queen Street. Moreover, his academy nudes were engraved [and otherwise copied, as below] until 1735. . . . Naked female models were forbidden at the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and to employ them in studios was extremely expensive. Chéron therefore based his ideas of female anatomy on the Antique and on Old Master paintings, especially those of Raphael."

|

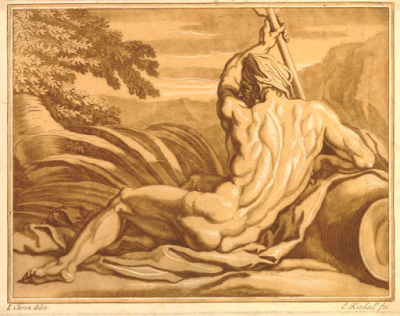

| Elisha Kirkall after Louis Chéron Model posed as Classical Soldier 1722 mezzotint British Museum |

|

| Elisha Kirkall after Louis Chéron Model posed as River God 1735 chiaroscuro woodcut with etching and mezzotint British Museum |

|

| Elisha Kirkall after Louis Chéron Model posed as Seated Prophet 1735 chiaroscuro woodcut with etching and mezzotint British Museum |

"The dissemination of Chéron's academy figures suggests that the French artist played a crucial role in English art education from 1711 to 1735 at least. His rigorous life-studies offered an alternative to illustrations of the male figure in drawing books."

|

| Jonathan Richardson, Senior Figg the Gladiator 1714 drawing Ashmolean Museum, Oxford |

"This drawing was executed by the artist, from the life, in 1714. At that time, Richardson was one of the directors of the Academy in Great Queen Street and was about to publish the first of his essays on art, The Theory of Painting of 1715. It is highly probable that this portrait of James Figg (d. 1734) was executed at the Academy and that the pugilist was one of the models who sat before the artists in Great Queen Street. Figg, one of the celebrated pugilists of his day, was an ideal model for the Life Class. He possibly also posed before artists attending the first St. Martin's Lane Academy in 1720-24."

|

| William Gandy Portrait of surgeon John Patch, Senior with dissected Human Forearm 1717 oil on canvas Royal Devon and Exeter Hospitals |

"The painting shows the surgeon demonstrating the dissection of the right forearm. This type of portrait was made famous by the frontispiece to Andreas Vesalius' De Humani corporis fabrica (Basle 1543). Rembrandt's Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp of 1632 is another obvious precedent. More generally, the human hand had theological and philosophical implications from the time of Aristotle and Galen. Its primary purpose is to grip, and it was regarded as the instrument of human civilization par excellence. The portrait of Patch is particularly interesting because new elements are added to the traditional iconography of the anatomist's portrait. Gandy and Patch, who were familiar with the symbology of the human hand, wanted the portrait to give a clear message: that knowledge in anatomy depended on the anatomist's ability to draw. The visualization of this statement is conveyed by four hands: the hand of the dissected forearm (the object of the anatomist's observations), the anatomist's right hand holding a drawing implement (the instrument by which the anatomist can attain a better knowledge of the object), his left hand supporting a book of anatomical studies (the repository in which the anatomist preserves past and present knowledge) and the drawing of the hand (the visualization of the anatomist's knowledge). William Patch, no doubt, could draw, as could the anatomist William Cowper before him, and the anatomist William Cheselden after him."

– quoted passages from The Artist's Model: its Role in British Art from Lely to Etty by Ilaria Bignamini and Martin Postle (exhibition catalogue, Nottingham University Art Gallery, 1991)