|

| Royal Academy of Arts Cast of the Farnese Hercules ca. 1790 plaster Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

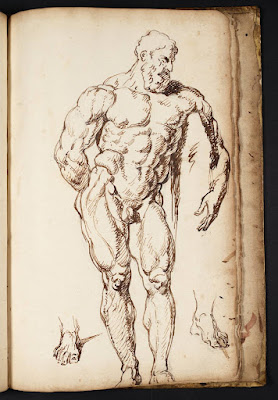

| Richard Dalton Farnese Hercules 1741 drawing Royal Collection, Windsor |

|

| Richard Dalton Farnese Hercules 1742 drawing Tate Britain |

"This morning Mr. Dalton came, as he had promised and brought some statues drawn in red chalk, that he said were for Lord Brooke, and some copies from the little Farnese that he told me were for your Ladyship. There is a very visible improvement from the first of his drawings to those last finished, which indeed were as good as any I have seen of the modern artists." – Lady Pomfret to Lady Hertford, 2 May 1741

"Eight of Dalton's drawings were published in 1770 by John Boydell as part of A Collection of Twenty Antique Statues Drawn after the Originals in Italy by Richard Dalton Esq. At the time of Dalton's drawing, the Farnese Hercules was in its unrestored state in the Palazzo Farnese. A cast of the figure also existed at the French Academy in Rome. At that time, not only were the extremities of the fingers missing on the left hand, but its legs were substitutes which had been made by Guglielmo della Porta on the advice of Michelangelo. In 1787, however, the statue's original legs were put back into place and the figure restored. It was subsequently sent to Naples [where it remains to the present day]. And yet, as Lady Pomfret's letter indicates – and a comparison of Dalton's drawing with the original confirms – the artist had almost certainly based his study on a reduced copy of the statue, of which there were numerous versions in plaster and bronze by the early 18th century."

|

| Joseph Highmore Study of a Cast of the Farnese Hercules ca. 1712-15 drawing Tate Britain |

|

| Domenico Corvi Portrait of artist David Allan painting a reduced copy of the Borghese Gladiator 1774 oil on canvas Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh |

|

| William Pether after Joseph Wright of Derby Three Artists studying a reduced copy of the Borghese Gladiator by lamplight 1769 mezzotint British Museum |

|

| Joseph Highmore Study of a cast of the Borghese Gladiator ca. 1712-15 drawing Tate Britain |

|

| William Etty Model posed as the Venus de' Medici ca. 1820 oil on card Courtauld Gallery, London |

"This oil study by Etty demonstrates the manner in which the living model at the Royal Academy Schools was sometimes required to emulate classical statuary. Here the female model takes up the pose of the Venus de Medici, even in the manner in which her hair is caught up behind her neck. The only major difference is that the pose of the antique statue has been reversed by the Visitor, presumably in the hope that the students would not simply refer back to drawings they had made of the cast, but rather approach the figure with fresh insight."

|

| Joseph Nollekens Venus de' Medici 1770 measured drawing Ashmolean Museum, Oxford |

"Nollekens' practice of taking careful measurements from classical statuary stemmed in part from his training in the workshop of the copyist and cast-maker Bartolomeo Cavaceppi in Rome, where precise measurements of original statues were necessary in order to replicate casts for collections. He would also have experienced this working method at the French Academy in Rome, where the technique of making large-scale copies of antique statuary was also taught. Nollekens, we know, made several replicas of classical statues for British collectors. . . . The system used by Nollekens to measure the Venus de Medici, which goes back ultimately to the organic theory of proportions devised by Polycleitos, is closely modeled on that which Gérard Audran had published in 1683 as Les proportions du corps humain measurées sur les plus belles figures de l'antiquité. (An English version was first published in 1718.) Rather than using a method of measurement based on custom (such as an inch or centimetre) Audran took as his unit of measurement the head of the particular statue."

|

| Richard Dalton Venus de' Medici ca. 1741-42 drawing Royal Collection, Windsor |

|

| Joseph Mallord William Turner Study of a cast of the Venus de' Medici ca. 1792 drawing Tate Britain |

"Turner was accepted as a student in the Royal Academy Schools in December 1789, on the recommendation of the Academician J.F. Rigaud. Turner attended the Antique Academy regularly until 1793, where his last recorded signature in the 'Plaister Academy' register is on 8 October. A.J. Finberg counted 137 separate attendances in the Antique Academy by Turner. . . . Although weak in terms of the realisation of the plastic form of the statue, Turner's Venus study reveals the manner in which the artist has attempted to show the shadows cast by the lamp which illuminated the statue from above."

|

| John Flaxman The Braschi Venus 1811 drawing Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Benjamin Robert Haydon Study of a cast of an Antinoüs ca. 1810-20 drawing British Museum |

|

| Joseph Nollekens The Capitoline Antinoüs 1770 measured drawing Ashmolean Museum, Oxford |

|

| Richard Parkes Bonington Study of a cast of the Dancing Faun ca. 1819-22 drawing Yale Center for British Art |

|

| David Wilkie Study of a cast of the Dancing Faun ca. 1805 drawing Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh |

"This drawing has traditionally been thought to have been drawn by Wilkie in 1799, to gain entry to the Trustees Academy in Edinburgh. It seems more plausible, however, to argue that it was the drawing with which the artist gained entry to the Antique Academy at the Royal Academy Schools in December 1805. Regarding his attempt to enter the Trustees Academy, Allan Cunningham noted how, despite a letter from the Earl of Leven to the Secretary George Thomson, 'his [Wilkie's] drawings failed to satisfy the eye of that gentleman; he looked at the drawings of the modest and timid boy, reperused the Earl's letter, shook his head, and finally refused to admit him.' It was only through Leven's personal appeal that Wilkie was eventually admitted, and the artist later confessed to Cunningham, 'I, for one, can allow no ill to be said of patronage; patronage made me what I am, for it is plain that merit had no hand in my admission.' John Burnet described Wilkie's attendance at the Trustees Academy: 'When Wilkie came to our class he had much enthusiasm of a queer and silent kind, and very little knowledge of drawing: he had made drawings, it is true, from living nature in that wide academy of the world, and chiefly from men or boys, such groups as chance threw his way; but in that sort of drawing on which taste and knowledge are desired, he was far behind the others who, without a tithe of his talent, stood in the same class. . . . It was not enough, for him, to say 'draw that antique foot, or draw this antique hand'; no, he required to know to what statue the foot or hand belonged; what was the action, and what the sentiment. He soon felt that in the true antique the action and sentiment pervade it from the crown of the head to the sole of the foot, and that unless this was known the fragment was not understood, and no right drawing of it could be made.' In May 1805 Wilkie went to London, and in July entered the Royal Academy Schools as a probationer."

– quoted passages from The Artist's Model: its Role in British Art from Lely to Etty by Ilaria Bignamini and Martin Postle (exhibition catalogue, Nottingham University Art Gallery, 1991)