|

| Alessandro Allori after Andreas Vesalius Study of écorché Figure ca. 1565 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Alessandro Allori after Andreas Vesalius Study of écorché Figure ca. 1565 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Alessandro Allori Study of animated Skeleton ca. 1565 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jacopo Bellini Samson with Slain Lion before 1470 drawing on vellum Musée du Louvre |

|

| Alonso Berruguete Seated Figure with Lowered Head before 1561 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Cavaliere d'Arpino (Giuseppe Cesari) Figure Study for Warrior before 1640 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| follower of Cavaliere d'Arpino (Giuseppe Cesari) Académie ca. 1600-1650 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

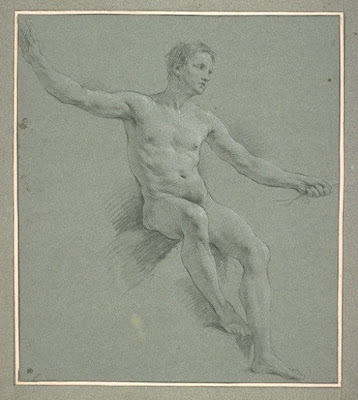

| Jean-Baptiste-Henri Deshays Académie ca. 1750 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jean-Baptiste-Henri Deshays Académie ca. 1750 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Charles Le Brun Figure Studies ca. 1670 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Charles Le Brun Figure Study ca. 1663 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| François Lemoyne Model posed as Louis XV giving Peace to Europe before 1737 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| attributed to Sebastiano Luciani Christ at the Column before 1547 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| attributed to Simon Vouet Study for Dead Christ before 1649 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

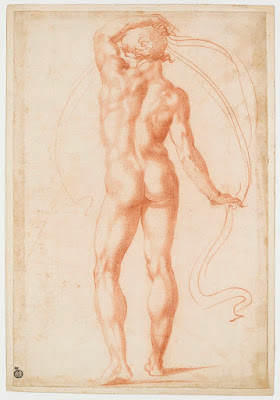

| Simon Vouet Study for Ignudo before 1649 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| attributed to Michelangelo Buonarroti Risen Christ ca. 1520-30 drawing Musée du Louvre |

Can honour's voice provoke the silent dust

Or flattery soothe the dull cold ear of death?

– Thomas Gray, from Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1751)

"I think that in the sketches, and even in the finished paintings of some artists, I have observed the effect of continuing to draw from the model, or from the naked figure, without due attention to the action of the muscles. I have seen paintings where the grouping was excellent and the proportions exact, yet the figures stood in attitudes when they were meant to be in action; they were fixed as statues and communicated to the spectator no idea of exertion or of motion. This sometimes proceeds, I have no doubt, from a long continued contemplation of the antique, but more frequently from drawing after the still and spiritless academy figure. The knowledge of anatomy is necessary to correct this; but chiefly a familiar acquaintance with the classification of the muscles and the peculiarities and effects of their action."

"The true use of the living figure is this: – after the artist has learnt the structure of the bones and the classification of the muscles, he should attentively observe the play of the muscles when thrown into action and attitudes of violent exertion; but chiefly he should mark the action of the muscles during the striking out of the limbs. He will soon, in such a course of observation, learn to distinguish between posture and action, and to avoid the tameness which results from neglecting the play of the muscles. And in this view, the painter, after having learnt to draw the figure, as it is usually termed, would do well to make the academy figure go through the exercise of pitching the bar, or throwing or striking. He will then find that it is chiefly in straining and pulling in a fixed posture that there is an universal tension and equal prominence of the muscles; and that in unrestrained actions only a few muscles rise strongly prominent, and are distinctly characteristic of that action."

– Charles Bell, from Essays on the Anatomy of Expression in Painting (1806)