|

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - January ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

|

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - February ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

|

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - March ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

|

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - April ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

|

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - May ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

|

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - June ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

|

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - July ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

|

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - August ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

|

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - September ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

|

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - October ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

|

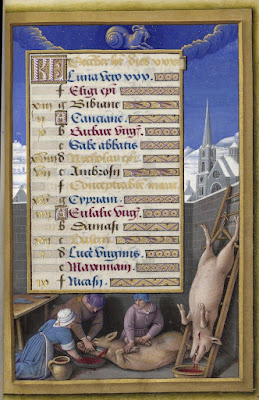

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - November ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

|

| Jean Bourdichon Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne Calendar Page - December ca. 1503-1508 tempera on vellum Bibliothèque nationale de France |

Noble Piety

Books of Hours are gatherings of the prayers that pertain to each canonical hour, and which the clergy were obliged to recite daily. Distinguished laypeople, as is here the case with Anne of Brittany, might also, as a sign of devotion, make daily use of a breviary (an authorized abridgement). The canonical hours of prayer are designated by ancient names: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, Nones, Vespers, Compline. Books of Hours also contained selected Scripture passages and pious poems.

Months of the Year

In the margins surrounding the text of his calendar pages Jean Bourdichon, identified by some art historians with the Master of Moulins (though there is uncertainty about this), brought together all of nature: birds, butterflies, flowers and fruit. For this volume Bourdichon also executed about fifty paintings that occupy entire pages, free of text. Within a fixed format, each month of the calendar is uniquely illustrated. Above the calendar proper (inset like other text pages) floats the appropriate sign of the zodiac: the Water Bearer for January. Below is a landscape with a seasonal scene: in the snow, a warmly dressed figure approaches the entrance to a house. February, under the sign of the Fish, is illustrated with a feast of stuffed poultry and charcuteries associated with Mardi Gras. March, under the sign of the Ram, shows the pruning of vines in front of a Renaissance château. In April, under the sign of the Bull, women pick flowers in a garden before a château with a fairy tale aspect and a certain resemblance to the palace at Urbino.

Compositional Ingenuity

Each of these landscapes seems to occupy the whole page, as if the rectangle of calendar text in the middle could be lifted off. The artist has worked out schemes that permit all the significant elements of each scene to be disposed around the edges. In general, what matters most in a picture tends to be placed in the center, but here the essential is found in the margins. This technique evolved from the border grotesques of illuminated manuscripts that gradually became more and more elaborate. One is reminded of the Essays of Montaigne, who was initially motivated by the text of the Discourse on Voluntary Servitude composed by his recently deceased friend La Boétie – a text circulated clandestinely – to write his own responses, as if shaping a funeral wreath for his friend.

Intertwined Symbols

The seasons following one another, the harsher and the kinder, ask also to be read as the seasons of a life. In the month of May, there is an image in a garden of twins, personified by a tree trimmed into three sections – rooted in an artificial hillock also ascending in three sections – with objects hanging from the branches, recalling the traditional May Day competition of climbing a greased pole to grab hanging treats. The viewer is meant to reflect on the progress from childhood to maturity, and thence to senescence. Every least morsel of vegetation solicites interpretation. This sort of symbolism strikes us as highly medieval, but in fact the same system endured through succeeding centuries, although the subtexts gradually took on more subtle concealments.

The Universe as Pipe Organ

In June, under the sign of Cancer, peasants are shown mowing, one sharpening a scythe. In July, under the sign of the Lion, the grain harvest begins in sight of a large farm building backed by naked mountains of rock. In August, peasants winnow the grain, their filled sacks accumulating in front of an urban edifice. There is a harmony between cosmic time and the system of liturgical time that humans are obliged scrupulously to observe: the latter is structured to align precisely with the divine order. If people do not succeed in doing what they are supposed to do at the time they are supposed to do it, everything will shift out of place and collapse in ruin.

Autumn and Winter

September, under the sign of Libra, is the season for harvesting vineyards: a worker treads grapes in a large vat to produce wine. In the month of October, under the sign of the Scorpion, the farming cycle recommences: behind sowers in the foreground, oxen till the land, at the horizon of which stands a city with its ramparts and monuments. November, under the sign of Sagittarius, carries us to the pigpen, where hogs are cared for and fattened. In December, under the sign of Capricorn, the pigs are killed for the Christmas feast and preserved to be eaten over the course of winter – in a landscape newly re-covered with snow.

– translated and adapted from Le Musée imaginaire de Michel Butor: 105 œuvres décisives de la peinture occidentale (Paris: Flammarion, 2019)