|

| Marco Angolo del Moro Mars and Venus before 1586 etching British Museum |

|

| Marco Angolo del Moro Hercules slaying the Hydra before 1586 etching and engraving Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Battista Angolo del Moro Hercules slaying the Hydra 1552 etching Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

|

| Battista Angolo del Moro after Giulio Romano Personification of the Seasons - Spring ca. 1570-73 etching Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Battista Angolo del Moro after Giulio Romano Personification of the Seasons - Summer ca. 1570-73 etching Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Battista Angolo del Moro after Giulio Romano Personification of the Seasons - Autumn ca. 1570-73 etching Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Battista Angolo del Moro after Giulio Romano Personification of the Seasons - Winter ca. 1570-73 etching Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Battista Angolo del Moro Mars and Venus with Cupid before 1573 oil on canvas private collection |

|

| Alessandro Allori Venus disarming Cupid (detail) ca. 1570 oil on canvas Musée Fabre, Montpellier |

|

| Alessandro Allori Venus disarming Cupid ca. 1570 oil on canvas Musée Fabre, Montpellier |

MANNERISM – A style applied to certain types of art produced ca. 1520 - ca. 1580, mainly in central Italy, and diffused in France, the Netherlands, Spain, and the imperial courts in Prague and Vienna. Mannerism is interposed in the history of styles between High Renaissance and Baroque art. There is little consensus, however, among historians as to the canon, the distinguishing formal characteristics, and the significance of Mannerist art. The word derives from the Italian maniera, which has a long history of usage in the literature of manners and the arts before being incorporated into a visual style label (by Luigi Lanzi in 1792). Maniera has neutral, favourable and pejorative meanings. . . . This critical polyvalance persists in modern definitions of Mannerism, which in turn colour our perceptions of the works of art to which they are attached. Mannerism has been variously defined as decadent; as a conscious rebellion against the classicizing ideals of the High Renaissance, symptomatic of 'anguish,' either of 'the age' or of 'neurotic' individuals, or of 'higher spirituality.' More recently Mannerism has been viewed as an art of courtly artifice, refinement and elegance, expressive works being excluded from the canon. Each of these definitions may apply with greater or lesser truth to some work of art of the 16th century. They err, as do all essentialist definitions of style, in postulating a single descriptive and explanatory principle. Mannerism is not a coherent movement on the 20th-century model of an association of artists pursuing a joint programme. Insofar as the term has general applicability, however, this depends on the following. Mannerist artists and their courtly or metropolitan audiences shared a certain sophistication, the knowledge of various artistic modes transcending local schools. In particular, they shared a reverence for High Renaissance art, notably the work of Michelangelo: his almost exclusive concentration on the human figure, his ideals of youthful grace or mature musculature, his formulae of contrapposto, etc. His use of the antique relief style for painting as well as sculpture was widely emulated. . . .

– excerpted from The Yale Dictionary of Art and Artists, by Erika Langmuir and Norbert Lynton (2000)

|

| Jacopo Bertoia Jupiter before 1574 oil on panel Christ Church, University of Oxford |

|

| Jacopo Bertoia Mars before 1574 oil on panel Christ Church, University of Oxford |

|

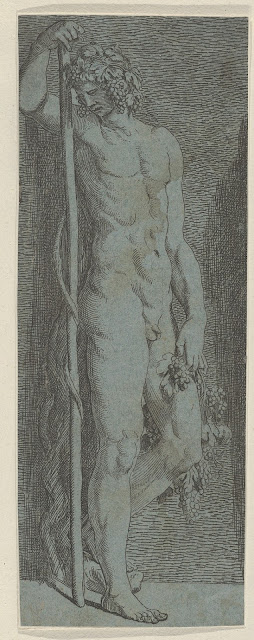

| Jacopo Bertoia Hercules before 1574 oil on panel Christ Church, University of Oxford |

|

| Taddeo Zuccaro Adoration of the Kings ca. 1555-60 oil on panel Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge |

|

| Federico Zuccaro Calumny ca. 1569-72 oil on canvas Royal Collection, Great Britain |

|

| Federico Zuccaro Dead Christ with Angels ca. 1560-70 oil on copper Galleria Borghese, Rome |