|

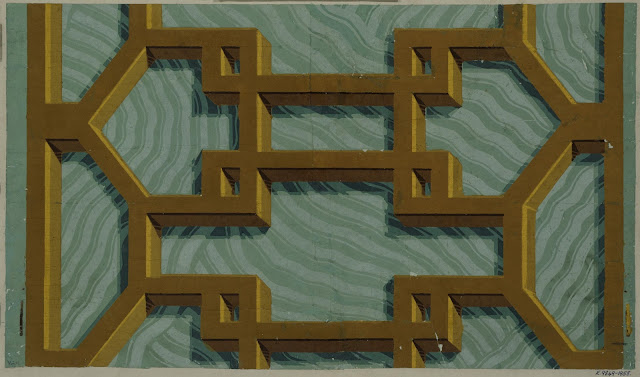

| Robert Jones for Frederick Crace & Son Chinoiserie Wallpaper for the Royal Pavilion, Brighton 1820 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Robert Jones for Frederick Crace & Son Chinoiserie Wallpaper for the Royal Pavilion, Brighton 1820 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| A.W. Pugin for Scott & Co. Foliate-Patterned Wallpaper 1850-51 block-printed and flocked Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| William Burges Wallpaper Frieze with Aesop's Fable of the Fox and the Crane ca. 1870 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

"Perhaps it was that darkening that called to my mind an article I had clipped from the Eastern Daily Press several months before, on the death of Major George Wyndham Le Strange, whose great stone manor house in Henstead stood beyond the lake. During the last War, the report read, Le Strange served in the anti-tank regiment that liberated the camp at Bergen Belsen on the 14th of April 1945, but immediately after VE-Day returned home from Germany to manage his great uncle's estates in Suffolk, a task he had fulfilled in exemplary manner, at least until the mid-Fifties, as I knew from other sources. It was at that time too that Le Strange took on the housekeeper to whom he eventuallly left his entire fortune: his estates in Suffolk as well as property in the centre of Birmingham estimated at several million pounds. According to the newspaper report, Le Strange employed this housekeeper, a simple young woman from Beccles by the name of Florence Barnes, on the explicit condition that she take the meals she prepared together with him, but in absolute silence. Mrs. Barnes told the newspaper herself that she abided by this arrangement, once made, even when her employer's life became increasingly odd. Though Mrs. Barnes gave only the most reticent of responses to the reporter's enquiries, my own subsequent investigations revealed that in the late Fifties Le Strange discharged his household staff and his labourers, gardeners and administrators one after another, that thenceforth he lived alone in the great stone house with the silent cook from Beccles, and that as a result the whole estate, with its gardens and park, became overgrown and neglected, while scrub and undergrowth encroached on the fallow fields. Apart from comments that touched upon these matters of fact, stories concerning the Major himself were in circulation in the villages that bordered on his domain, stories to which one can lend only limited credence. They drew, I imagine, on the little that reached the outside world over the years, rumours from the depths of the estate that occupied the people who lived in the immediate vicinity. Thus in a Henstead hostelry, for example, I heard it said that in his old age, since he had worn out his wardrobe and saw no point in buying new clothes, Le Strange would wear garments dating from bygone days which he fetched out of chests in the attic as he needed them. There were people who claimed to have seen him on occasion dressed in a canary-yellow frock coat or a kind of mourning robe of faded violet taffeta with numerous buttons and eyes. Le Strange, who had always kept a tame cockerel in his room, was reputed to have been surrounded, in later years, by all manner of feathered creatures: by guinea fowl, pheasants, pigeons and quail, and various kinds of garden and song birds, strutting about him on the floor or flying around in the air. Some said that one summer Le Strange dug a cave in his garden and sat in it day and night like St. Jerome in the desert. Most curious of all was a legend that I presume to have originated with the Wrentham undertaker's staff, to the effect that the Major's pale skin was olive-green when he passed away, his goose-grey eye was pitch-dark, and his snow-white hair had turned to raven-black. To this day I do not know what to make of such stories. One thing is certain: the estate and all its adjunct properties was bought at auction by a Dutchman last autumn, and Florence Barnes, the Major's loyal housekeeper, lives now with her sister Jemima in a bungalow in her home town of Beccles, as she had intended."

– W.G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn, published in German in 1995, translated by Michael Hulse and published by New Directions in English in 1998

|

| William Morris for Morris & Co. Acanthus Wallpaper 1875 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| John Henry Dearle for Morris & Co. Blackthorn Wallpaper 1892 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Walter Crane for Jeffrey & Co. Singing Birds Wallpaper 1893 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Walter Crane for Jeffrey & Co. Day Lily Wallpaper 1897 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

"Recalling the uncertainty I then felt brings me back to the Argentinian tale I have referred to before, a tale which deals with our attempts to invent secondary or tertiary worlds. The narrator describes dining with Adolfo Bioy Casares in a house in Calle Gaona in Ramos Mejía one evening in 1935. He relates that after dinner they had a long and rambling talk about the writing of a novel that would fly in the face of palpable facts and become entangled in contradictions in such a way that few readers – very few readers – would be able to grasp the hidden, horrific, yet at the same time quite meaningless point of the narrative. At the end of the passage that led to the room where we were sitting, the author continues, hung an oval, half-fogged mirror that had a somewhat disquieting effect. We felt that this dumb witness was keeping a watch on us, and thus we discovered – discoveries of this kind are almost always made in the dead of night – that there is something sinister about mirrors. Bioy Casares then recalled the observation of one of the heresiarchs of Uqbar, that the disturbing thing about mirrors, and also the act of copulation, is that they multiply the number of human beings. I asked Bioy Casares for the source of this memorable remark, the author writes, and he told me that it was in the entry on Uqbar in the Anglo-American Cyclopaedia. As the story goes on, however, it is revealed that this entry is nowhere to be found in the encyclopaedia in question, or rather, it appears uniquely in the copy bought years earlier by Bioy Casares, the twenty-sixth volume of which contains four pages that are not in any other copy of the edition in question, that of 1917. It thus remains unclear whether Uqbar ever existed or whether the description of this unknown country might not be a case similar to that of Tlön, the encyclopaedists' project to which the main portion of the narrative in question is devoted and which aimed at creating a new reality, in the course of time, by way of the unreal. The labyrinthine construction of Tlön, reads a note added to the text in 1947, is on the point of blotting out the known world. The language of Tlön, which hitherto no one had mastered, has now invaded the academies; already the history of Tlön has superseded all that we formerly knew or thought we knew; in historiography, the indisputable advantages of a fictitious past have become apparent. Almost every branch of learning has been reformed. A ramified dynasty of hermits, the dynasty of the Tlön inventors, encylopaedists and lexicographers, has changed the face of the earth. Every language, even Spanish, French and English, will disappear from the planet. The world will be Tlön. But, the narrator concludes, what is that to me? In the peace and quiet of my country villa I continue to hone my tentative translation, schooled on Quevodo, of Thomas Browne's Urn Burial (which I do not mean to publish)."

– W.G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn, published in German in 1995, translated by Michael Hulse and published by New Directions in English in 1998

|

| C.F.A. Voysey for Essex & Co. The Tierney Wallpaper ca. 1897 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| C.F.A. Voysey for Essex & Co. The Syracuse Wallpaper 1902-1903 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Allen Francis Vigers for Jeffrey & Co Mallow Wallpaper ca. 1899-1909 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Allen Francis Vigers for Jeffrey & Co. Japanese Rose Wallpaper ca. 1899-1909 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Albert Griffiths for Jeffrey & Co Rhododendrons Wallpaper ca. 1910 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Metford Warner for Jeffrey & Co. Juno Wallpaper 1920 block-printed Victoria & Albert Museum, London |