|

| George Luks A Clown 1929 oil on canvas Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

|

| John Singer Sargent Sketch for Chiron and Achilles ca. 1922-24 oil on canvas Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

|

| George Bellows Emma and Her Children 1923 oil on canvas Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

|

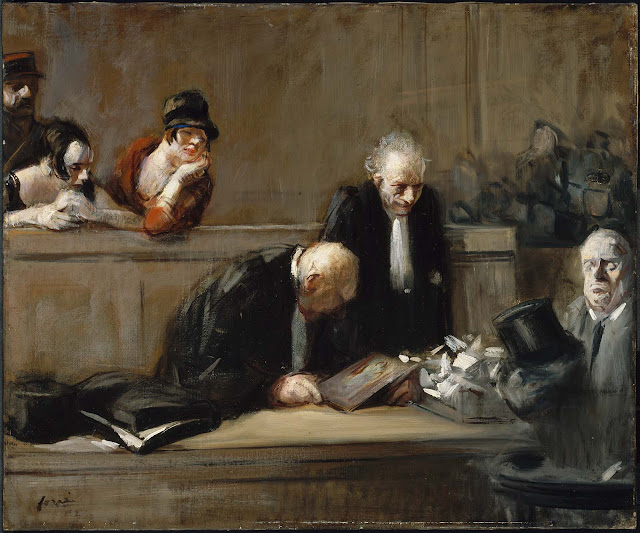

| Jean-Louis Forain Witness Confounded 1926 oil on canvas Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

Lament

Suddenly, after you die, those friends

who never agreed about anything

agree about your character.

They're like a houseful of singers rehearsing

the same score:

you were just, you were kind, you lived a fortunate life.

No harmony. No counterpoint. Except

they're not performers;

real tears are shed.

Luckily, you're dead; otherwise

you'd be overcome with revulsion.

But when that's passed,

when the guests begin filing out, wiping their eyes

because, after a day like this,

shut in with orthodoxy,

the sun's amazingly bright,

though it's late afternoon, September –

when the exodus begins,

that's when you'd feel

pangs of envy.

Your friends the living embrace one another,

gossip a little on the sidewalk

as the sun sinks, and the evening breeze

ruffles the women's shawls –

this, this, is the meaning of

"a fortunate life": it means

to exist in the present.

– Louise Glück, from Ararat (Ecco Press, 1990)

|

| John Duncan The Unicorns 1920 tempera on canvas Dundee Art Galleries and Museums |

|

| Pablo Picasso The Bather 1922 oil on panel Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut |

|

| Charles Sheeler Nude 1920 drawing (after a photograph) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

|

| John Singer Sargent Sketch for Hercules and the Hydra ca. 1921-25 drawing Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

|

| Tina Modotti Stairs, Mexico City ca. 1924-26 gelatin silver print Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

| George Luks View of Beacon Street from Boston Common ca. 1923 oil on canvas Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

Civilization

It came to us very late:

perception of beauty, desire for knowledge.

And in the great minds, the two often configured as one.

To perceive, to speak, even on subjects inherently cruel –

to speak boldly even when the facts were, in themselves, painful or dire –

seemed to introduce among us some new action,

having to do with human obsession, human passion.

And yet something, in this action, was being conceded.

And this offended what remained in us of the animal:

it was enslavement speaking, assigning

power to forces outside ourselves.

Therefore the ones who spoke were exiled and silenced,

scorned in the streets.

But the facts persisted. They were among us,

isolated and without pattern; they were among us,

shaping us –

Darkness. Here and there a few fires in doorways,

wind whipping around the corners of buildings –

Where were the silenced, who conceived these images?

In the dim light, finally summoned, resurrected.

As the scorned were praised, who had brought

these truths to our attention, who had felt their presence,

who had perceived them clearly in their blackness and horror

and had arranged them to communicate

some vision of their substance, their magnitude –

In which the facts themselves were suddenly

serene, glorious. They were among us,

not singly, as in chaos, but woven

into relationship or set in order, as though life on earth

could, in this one form, be apprehended deeply

though it could never be mastered.

– Louise Glück, from The Seven Ages (Ecco Press, 2001)

|

| Reginald Marsh Paris Theater 1929 oil on canvas Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut |

|

| Charles Demuth Longhi on Broadway 1928 oil on board Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

|

| Francis Ernest Jackson The Manuscript ca. 1921 tempera on panel Ashmolean Museum, Oxford |

|

| Charles Sheeler Peaches in a Bowl 1925 oil on canvas Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |