|

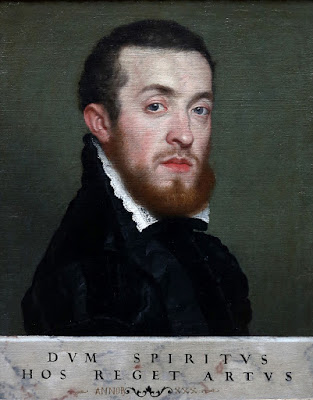

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of Pietro Secco Suardo (detail) 1563 oil on canvas Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

|

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of Pietro Secco Suardo 1563 oil on canvas Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

|

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of Pietro Secco Suardo (detail) 1563 oil on canvas Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

|

| Giambattista Moroni St Clare of Assisi 1548 oil on canvas Palazzo Pretorio, Trento |

|

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of a Young Gentleman ca. 1560 oil on canvas National Gallery, London |

|

| Giambattista Moroni The Lawyer ca. 1570 oil on canvas National Gallery, London |

|

| Giambattista Moroni The Tailor ca. 1565-70 oil on canvas National Gallery, London |

|

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of a Gentleman in Black ca. 1567 oil on canvas Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan |

|

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of a Young Gentleman ca. 1564-65 oil on canvas National Gallery, London |

|

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of a Knight with Jousting Helmet ca. 1554-58 oil on canvas National Gallery, London |

|

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of Giangrisostomo Zanchi ca. 1566 oil on canvas Accademia Carrara, Bergamo |

|

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of Gian Ludovico Madruzzo ca. 1551-52 oil on canvas Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of Canon Ludovico di Terzi ca. 1559-60 oil on canvas National Gallery, London |

|

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of a Man with Raised Eyebrows ca. 1570-75 oil on canvas National Gallery, London |

|

| Giambattista Moroni Portrait of a Lady ca. 1556-60 oil on canvas National Gallery, London |

"In Renaissance Italy, one of the aims of portraiture was to make the absent seem present through naturalistic representation of the sitter. This notion – that art can capture an individual exactly as he or she appears – is exemplified in the the work of Giovanni Battista Moroni. The artist spent his entire career in and around his native Bergamo, a region in Lombardy northeast of Milan, and left a corpus of portraits that far outnumbers those of his contemporaries who worked in major artistic centers, including Titian in Venice and Bronzino in Florence. . . . According to an anecdote first published in 1648 in Carlo Ridolfi's Le meraviglie dell'arte, Titian, when approached by a group of would-be patrons, recommended that they instead sit for Moroni, praising his ritratti di naturale (portraits from life). The naturalism for which Moroni was most acclaimed, however, also became a point of criticism: his apparent faithfulness to his models caused some to dismiss him as a mere copyist of nature, an artist without "art" – that is, without selection, editing, or adherence to ideals of beauty. Bernard Berenson derided him in 1907 as an uninventive portraitist who "gives us sitters no doubt as they looked." Subsequent scholars restored his reputation; the art historian Roberto Longhi, for example, in 1953 praised Moroni's "documents" of society that were unmediated by style, crediting him with a naturalism that anticipated Caravaggio. But Moroni's characterization as an artist who faithfully recorded the world around him – whether understood as a positive quality or a weakness – has obscured his creativity and innovation as a portraitist."

– from curator's notes to the 2019 Moroni exhibition at the Frick Collection, New York