|

| Jean-Louis Laneuville Study for Sibyl 1810 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jacques-Louis David Study for Leonidas at Thermopylae ca. 1814 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jacques-Louis David Study for Leonidas at Thermopylae ca. 1814 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jacques-Louis David Hector's Farewell to Andromache 1812 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard Homer and the Shepherds ca. 1815-20 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard Infant Pyrrhus at the Court of Glaucias of Taulantii 1814 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Anonymous French Artist Antiquities Gallery at the Louvre (with ancient sculpture of The Tiber, looted from the Vatican) ca. 1810 drawing, with watercolor Musée du Louvre |

|

| Anonymous French Artist Antiquities Gallery at the Louvre (with ancient sculpture of The Nile, looted from the Vatican) ca. 1810 drawing, with watercolor Musée du Louvre |

|

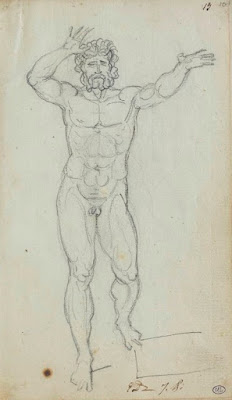

| Guillaume Lethière Study for The Death of Verginia ca. 1828 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Guillaume Lethière Study for The Death of Verginia ca. 1828 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Guillaume Lethière Study for The Death of Verginia ca. 1828 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Guillaume Lethière Study for The Death of Verginia ca. 1828 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Guillaume Lethière Study for The Death of Verginia ca. 1828 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Guillaume Lethière Study for The Death of Verginia ca. 1828 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Guillaume Lethière The Death of Verginia 1828 oil on canvas Musée du Louvre |

"This outrage was followed by another, committed in Rome, which was inspired by lust and was no less shocking in its consequences than that which had led, through the rape and the death of Lucretia, to the expulsion of the Tarquinii from the City and from their throne; thus not only did the same end befall the decemvirs as had befallen the kings, but the same cause deprived them of their power. Appius Claudius was seized with the desire to debauch a certain maiden belonging to the plebs. The girl's father, Lucius Verginius, a centurion of rank, was serving on Algidus, a man of exemplary life at home and in the army. His wife had been brought up in the same principles, and his children were being trained in them. He had betrothed his daughter [Verginia] to the former tribune Lucius Icilius, an active man of proven courage in the cause of the plebeians. She was a grown girl, remarkably beautiful, and Appius, crazed with love, attempted to seduce her with money and promises. But finding that her modesty was proof against everything, he resolved on a course of cruel and tyrannical violence. He commissioned Marcus Claudius, his client, to claim the girl as his slave, and not to yield to those who demanded her liberation, thinking that the absence of the maiden's father afforded an opportunity for the wrong. As Verginia was entering the Forum – for there, in booths, were the elementary schools – the minister of the decemvir's lust laid his hand upon her, and calling her the daughter of his bond-woman and herself a slave, commanded her to follow him, and threatened to drag her off by force if she hung back. Terror made the maiden speechless, but the cries of her nurse imploring help of the Quirites quickly brought a crowd about them. The names of Verginius her father and of her betrothed Icilius were known and popular. Their acquaintance were led to support the girl out of regard for them; the crowd was influenced by the shamelessness of the attempt. She was already safe from violence, when the claimant protested that there was no occasion for the people to become excited; he was proceeding lawfully, not by force. He then summoned the girl to court. She was advised by her supporters to follow him, and they went before the tribunal of Appius. The plaintiff acted out a comedy familiar to the judge, since it was he and no other who had invented the plot: The girl had been born, said Marcus, in his house, and had thence been stealthily conveyed to the home of Verginius and palmed off upon him as his own; he had good evidence for what he said, and would prove it even though Verginius himself were judge, who was more wronged than he was; meanwhile it was right that the hand-maid should follower her master. The friends of the girl said that Verginius was absent on the service of the state; he would be at hand in two days' time if he were given notice of the matter; it was unjust that a man should be involved in litigation about his children when away from home; they therefore requested Appius to leave the case open until the father arrived, and in accordance with the law he had himself proposed, grant the custody of the girl to the defendants, nor suffer a grown maiden's honour to be jeopardized before her freedom should be adjudicated."

* * *

"But in the City, as the citizens at break of day were standing in the Forum, agog with expectation, Verginius, dressed in sordid clothes and leading his daughter, who was also meanly clad and was attended by a number of matrons, came down into the market-place with a vast throng of supporters. He then began to go about and canvass people, and not merely to ask their aid as a favour, but to claim it as his due, saying that he stood daily in the battle-line in defence of their children and their wives; that there was no man of whom more strenuous and courageous deeds in war could be related – to what end, if despite the safety of the City those outrages which were dreaded as the worst that could follow a city's capture must be suffered by their children? Pleading thus, as if in a kind of public appeal, he went about amongst the people. Similar appeals were thrown out by Icilius; but the women who attended them were more moving, as they wept in silence, than any words. In the face of all these things Appius hardened his heart – so violent was the madness, as it may more truly be called than love, that had overthrown his reason – and mounted the tribunal. The plaintiff was actually uttering a few words of complaint, on the score of having been balked of his rights the day before through partiality, when, before he could finish his demand, or Verginius be given an opportunity to answer, Appius interrupted him. The discourse with which he led up to his decree may perhaps be truthfully represented in some one of the old accounts, but since I can nowhere discover one that is plausible, in view of the enormity of the decision, it seems my duty to set forth the naked fact, upon which all agree, that he adjudged Verginia to him who claimed her as his slave. At first everybody was rooted to the spot in amazement at so outrageous a proceeding, and for a little while after the silence was unbroken. Then, when Marcus Claudius was making his way through the group of matrons to lay hold upon the girl, and had been greeted by the women with wails and lamentations, Verginius shook his fist at Appius and cried, "It was to Icilius, Appius, not to you that I betrothed my daughter; and it was for wedlock, not dishonour, that I brought her up. Would you have men imitate the beasts of the field and the forest in promiscuous gratification of their lust? Whether these people propose to tolerate such conduct I do not know: I cannot believe that those who have arms will endure it."

* * *

"Then Verginius, seeing no help anywhere, said, "I ask you, Appius, first to pardon a father's grief if I have somewhat harshly inveighed against you; and then to suffer me to question the nurse here, in the maiden's presence, what all this means, that if I have been falsely called a father, I may go away with a less troubled spirit." Permission being granted, he led his daughter and the nurse apart, to the booths near the shrine of Cloacina, now known as the "New Booth," and there, snatching a knife from a butcher, he exclaimed, "Thus, my daughter, in the only way I can, do I assert your freedom!" He then stabbed her to the heart, and, looking back to the tribunal, cried, "'Tis you, Appius, and your life I devote to destruction with this blood!" The shout which broke forth at the dreadful deed roused Appius, and he ordered Verginius to be seized. But Verginius made a passage for himself with his knife wherever he came, and was also protected by a crowd of men who attached themselves to him, and so reached the City gate. Icilius and Numitorius lifted up the lifeless body and showed it to the people, bewailing the crime of Appius, the girl's unhappy beauty, and the necessity that had constrained her father. After them came the matrons crying aloud, "Was it on these terms that children were brought into the world? Were these the rewards of chastity?" – with such other complaints as are prompted at a time like this by a woman's anguish, and are so much more pitiful as their lack of self-control makes them the more give way to grief."

– Livy, from Book 3 of Ab Urbe Condita, translated as The History of Rome by Benjamin Oliver Foster and published as part of the Loeb Classical Library in 1922

– Livy, from Book 3 of Ab Urbe Condita, translated as The History of Rome by Benjamin Oliver Foster and published as part of the Loeb Classical Library in 1922