|

| Richard Wyndham The Medway near Tonbridge 1936 oil on canvas Manchester Art Gallery |

|

| Jan Lievens Edge of a Wood before 1674 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Claude Rogers Clover Field, Somerton, Suffolk 1959 oil on canvas Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge |

|

| Paul Flandrin La Promenade de Poussin (bank of the Tiber) 1835 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| William James Müller Sketch in Wales ca. 1835 oil on board Museums Sheffield, Yorkshire |

|

| Roelant Savery Rocky Landscape with a Valley ca. 1606 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jean-Charles-Joseph Rémond Mountain Landscape with Road to Naples ca. 1821-25 oil on canvas Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

|

| Peter Paul Rubens Study of Trees ca. 1618 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Ernest Procter Penlee Point 1926-27 oil on panel Government Art Collection, London |

|

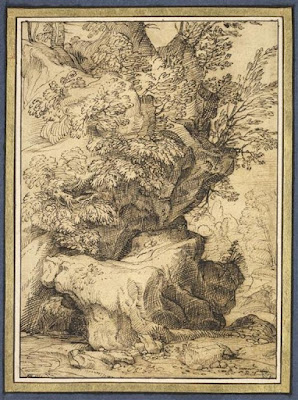

| Girolamo Muziano Hilltop with Trees before 1592 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Brendan Neiland Cumbrian Landscape No. 1 1982 oil-on-board- Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery, Carlisle, Cumbria |

|

| Aelbert Cuyp Wooded Landscape with Shepherds 1642-44 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Paul Nash Landscape of the Moon's Last Phase 1944 oil on canvas Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool |

|

| Paul Bril Road between Wooded Banks before 1626 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Arnold Böcklin Campagna Landscape ca. 1859 oil on canvas Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin |

|

| Claude Lorrain Trees ca. 1630 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Childe Hassam September Clouds 1891 pastel on canvas Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid |

|

| attributed to Agostino Carracci Trees growing on Rocks before 1602 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Giovanni Fattori Study of Trees ca. 1870 oil on canvas Pinacoteca della Città Metropolitana di Bari |

"The most obstinate realist is still compelled, in his rendering of nature, to make use of certain conventions of composition or of execution. If the question is one of composition, he cannot take an isolated piece of painting or even a collection of them and make a picture from them. He must certainly circumscribe the idea in order that the mind of the spectator shall not float about in an ensemble that has, perforce, been cut to bits; otherwise art would not exist. When a photographer takes a view, all you ever see is a part cut off from a whole: the edge of the picture is as interesting as the centre; all you can do is to suppose an ensemble, of which you see only a portion, apparently chosen by chance. . . . In the presence of nature herself, it is our imagination that makes the picture: we see neither the blades of grass in a landscape nor the accidents of the skin in a pretty face. Our eye, in its fortunate inability to perceive these infinitesimal details, reports to our mind only the things which it ought to perceive; the latter, again, unknown to ourselves, performs a special task; it does not take into account all that the eye presents to it; it connects the impressions it experiences with others which it received earlier, and its enjoyment is dependent on its disposition at the time. That is so true that the same view does not produce the same effect when taken in two different aspects."

– Eugène Delacroix, from the Journals (1859), translated by Walter Pach (1938)