|

| Théophile Steinlen Model on Bed ca. 1895 oil on canvas Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

|

| Félix Vallotton Cadaver 1894 oil on canvas Musée de Grenoble |

|

| Edgar Degas After the Bath ca. 1886 pastel Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

|

| Ford Madox Brown Haydee discovering the Body of Don Juan (scene from the mock-epic poem by Byron) ca. 1869-78 oil on canvas Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

|

| Henry Fuseli Eriphyle and the Erinyes 1810 wash drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| William Blake Pity ("pity like a naked, newborn babe" – Macbeth) ca. 1795 colour print with hand-coloring Tate Britain |

|

| Nicola Malinconico The Good Samaritan ca. 1703-1706 oil on canvas Palazzo Pretorio, Prato |

|

| Antonio Molinari The Good Samaritan before 1704 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Hans von Aachen The Good Samaritan ca. 1570-80 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Simon Vouet Académie before 1649 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Luca Saltarello Dead Christ before 1645 oil on canvas private collection |

|

| Cornelis Bloemaert Ixion ca. 1655-90 engraving Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

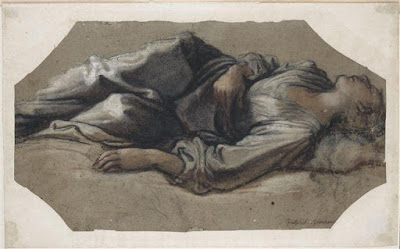

| Giovanni Mannozzi (Giovanni da San Giovanni) Study of Sleeping Woman ca. 1620 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Cavaliere d'Arpino (Giuseppe Cesari) Figure of a Dead Man ca. 1595-96 drawing (study for fresco, Palazzo dei Conservatori, Rome) Musée du Louvre |

|

| Cristóvão de Figueiredo Martyrdom of St Hippolytus ca. 1520-30 oil on panel Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon |

|

| Ancient Rome Funerary Monument of Flavius Agricola 2nd century AD marble (discovered in 1623 when erecting Bernini's Vatican Baldacchino) Indianapolis Museum of Art |

"Many years ago, whilst dissecting a lion, in my early youth, I was amazingly impressed with its similarity as well as its difference in muscular and bone construction to the human figure. It was evident the lion was but a modification of the human being, varied in organic construction and muscular arrangement, only where it was necessary he should be, that his bodily powers might suit his instincts, his propensities, his appetites, and his lower degree of reasoning power. On comparing the two, I found the human being stood erectly on two feet, the lion horizontally on four. On placing the lion on his two hind feet, resting on the heel and toes like the human being, I found he could not remain so; I found he had no power of grasping with his fore-paws (answering to the human hand, and but a modification); I found he could not move his fore-paw arms right from the shoulder, nor his hind-feet limbs right from the hip; I found his feet flat, his body long, his brain diminished, his eyes above the centre of his head, his jaw immense, and vast muscle occupying that portion of the skull, to assist the action of the jaw, which is filled by brain in a human creature; I found his spine long, his pan-bone narrow, his inner ancle lower than the outer, his chest contracted, and his fore-arm as long as his upper-arm. I put down these distinctions as points characteristic in head and figure of a brutal and unintellectual being."

"I then examined the man: I found his power of grasping with his hand, by the action of his thumb, perfect; I found the motion of his arm free from the shoulder-joint, and his thigh free from the hip; I found his feet arched, his inner ancle the highest, his pan-bone large, which, by resistance to the action of the great extensor of the legs, increases their power, his eyes at the centre of his skull, his upper-arm longer than the fore-arm, his spine short, and his brain enormous. I put down these distinctions as characteristic in face and figure of a superior and intellectual being."

"These differences were facts – they were intentional, or accidental! – they were formed by the Creator, or they were not! – if they were as they were, there was reason in the differences, and that reason issued from the Creator's mind. Surely, then, it was justifiable to lay down a principle of form from ascertaining these distinctions."

– Benjamin Robert Haydon, from Anatomy as the Basis of Drawing (1835)