|

| George Romney Lady Hamilton playing a Lyre ca. 1785 drawing National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

|

| Georg Philipp Rugendas Académie 1699 drawing Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart |

|

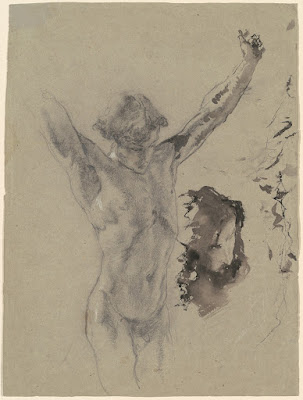

| Gaetano Gandolfi Académie ca. 1760 drawing National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

|

| Gerbrand van den Eeckhout Study of Young Man ca. 1640 drawing Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Mosé Bianchi Figure Study and Head of Christ ca. 1879 drawing National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

|

| attributed to Gianlorenzo Bernini Crouching Figure before 1680 drawing Gemäldegalerie, Dresden |

|

| Robert Blyth after John Hamilton Mortimer The Captive 1781 etching Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Louis-Roland Trinquesse Study of a Lady of Fashion ca. 1780-90 drawing Morgan Library, New York |

|

| Pietro Testa Standing Figures before 1650 drawing Morgan Library, New York |

|

| Giambattista Tiepolo Half-Length Figure Study 1752 drawing Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart |

|

| Wilhelm Lehmbruck Seated Youth 1917 plaster National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

|

| Theodor Kittelsen Académie 1874-76 drawing National Gallery of Norway, Oslo |

|

| Rockwell Kent Mast Head 1926 wood-engraving Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio |

|

| Anonymous Italian Artist after Pietro Perugino Archer ca. 1500 drawing National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

|

| Anonymous Italian Artist Seated Man tuning a Lute ca. 1550-75 drawing Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum |

|

| Johan Gørbitz Académie ca. 1820 oil on paper, mounted on canvas National Gallery of Norway, Oslo |

"An extraordinary wealth of documents and memoirs reveals a series of occurrences which included so many accidents and mistakes that even today, no longer gripped by the anguishing news of 1527, we find it hard to think of so great an accumulation of mishaps as anything but an act of fate. Some kind of underlying determinism seems to control this sequence of fortuitous events. It is for this reason that we felt obliged to stress the revelatory obsessions which, through astrologic or prophetic calculations, constitute noteworthy mental blocks and deviations. There are cases in which the modalities of the imagination become the stuff of historical moments. The events themselves – meetings between people, troop movements, and so on – ultimately converge on the same catastrophic path, making it difficult for the historian to replace in their proper perspective the hesitations and doubts that were the very mark of the situation. Without realizing it, there is a predisposition to the "fatalistic" version of this all too spectacular period of the Renaissance. When discussing an irresistible impulse, one discards alternatives and loses sight of the uncertainties, lost opportunities, or contrary impulses that might have arisen. We have therefore directed all our attention to the maze of contradictions and ambiguities through which we have the good fortune to be led by a masterful guide, Guicciardini [Francesco Guicciardini's History of Italy was written in the early 1530s and first published in the early 1560s]. We have had to consider that little-known historical reality – a prolonged moment of confusion. It is remarkable indeed that in April, at the very moment when auguries and prophecies were pouring in, Clement, trusting the word of the viceroy, Lannoy, demobilized the papal troops that were his only effective defense. This can be read as a mental lapse, bad judgement, or mistaken information. This also suggests the impulse to run away, which propels the victim toward the very thing he wants to escape."

– André Chastel, The Sack of Rome, 1527, translated by Beth Archer, 1983 (expanded from the A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, 1977, and published by Princeton University Press and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)