|

| Farnese Caracalla Roman marble bust 3rd century AD National Archaeological Museum, Naples |

"It is not known where the Farnese Caracalla came from – perhaps from one of the two great collections of Imperial heads whose discovery was recorded by Vacca writing in 1594 or earlier, perhaps from another collection; for Aldrovandi, in 1556, recorded examples in five Roman palaces." Among these multiple copies, "the Farnese version is still the best-known and probably the most admired." It was often called Frowning Caracalla.

|

| Anonymous Italian sculptor Farnese Caracalla 18th century copy - marble and bronze bust Victoria & Albert Museum |

"The impact of the turned head and ferocious gaze of this bust was given great historical resonance by the fact that it represented an emperor whose murder of his own brother and whose ruthless rule were familiar to every educated European. As one looked at the bust, or rather was looked at by it (de Brosses claimed that it quite frightened him) the past suddenly and dramatically became present. The bust was believed to be the last, or one of the last, great works of art of antiquity – 'the last effort of Roman Sculpture', 'le dernier soupir de la Sculpture Romaine'.

|

| Bartolomeo Cavaceppi Farnese Caracalla ca. 1750-70 copy - marble bust Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

"Busts of this type are acknowledged as portraits of Caracalla (joint emperor AD 211-12 and emperor AD 212-17). During the last century, scholars, pointing to the ancient accounts of the emperor's ambitions and iconography, have suggested that the busts are intended to display the sublime distraction of a self-styled successor to Alexander the Great. It is no longer supposed that the emperor intended to exhibit his bestial nature 'to the dismay and horror of his subjects'."

|

| Lucius Junius Brutus bronze Italian work inspired by earlier Greek models Capitoline Museum |

The sculpted portrait identified as Lucius Junius Brutus (above) quickly became an object of reverence in Rome after Cardinal Rodolfo Pio da Carpi bequeathed it to the state in 1564. "The fame of this striking bust depended to a notable extent on the belief that it portrayed the legendary founder of the Roman Republic. The first printed reference to it appears to take this for granted. ... Ancient historians recorded that in remote antiquity a bronze statue of Brutus, holding a dagger, had been placed on the Capitol. Knowledge of this may well have prompted Cardinal Pio da Carpi's bequest – indeed, by the beginning of the seventeenth century it was being suggested that the head, then on the Capitol, was a fragment of this very statue."

|

| Jacques-Louis David Lucius Junius Brutus 1789 drawing British Museum |

In the same year as the French Revolution (and not coincidentally) Jaques-Louis David recorded the features of the bronze Brutus in the drawing above. "This was the only work of art to be specifically named among the hundred that the Pope agreed to hand over to the French Republic under the terms of the armistice signed in Bologna on 23 June 1796 and ratified by the Treaty of Tolentino in the following year." It was subsequently venerated in Paris – as an emblem of austere civic virtue – until the defeat at Waterloo in 1815 permitted its return to Rome.

|

| Heinrich Guttenberg Portraits of Lucius Junius Brutus ca. 1808-1816 engraving Philadelphia Museum of Art |

|

| Lucius Junius Brutus copy of the bronze bust in the Capitoline Museum 19th century Royal Collection, Great Britain |

A life-size bronze copy (immediately above) was purchased in 1847 by Prince Albert for Osborne House through agents in Rome. This Roman copy appears to be more closely based on David's drawing than on the original antique. "Winckelmann had hinted that he had reservations about the name traditionally given to this head. Within a short time of its return to Rome, Visconti too exercised scholarly caution when trying to determine whether or not it really represented the hero who had been so largely responsible for its fame. In the end he merely emphasized that, as everyone knew, the bust on which the head had been placed was clearly of a different date, and he left open the question of identity. Few travelers to Rome were, however, prepared to attend to such scruples and thereby to forego the potent fascination exerted by the 'stern inexorable severity' of Lucius Junius Brutus."

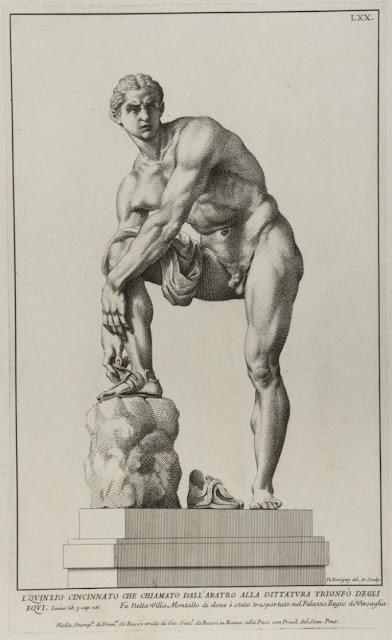

The marble statue below – formerly known as Cincinnatus – was recorded in Rome during the late 16th century, but then became one of the first important marbles to leave Italy. In 1685 it was purchased by Louis XIV for Versailles, and is now in the Louvre.

|

| Cincinnatus Roman marble copy of an earlier Greek bronze acquired by Louis XIV in 1685 Louvre |

"The base of the Cincinnatus was restored with a ploughshare on it, and the statue was believed from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century to represent Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, the patriot, whom Livy describes as summoned from his small farm to take command of the Roman armies against the Sabines and become dictator of the city. However, to Winckelmann (who pointed out that nudity would have been incongruous for Cincinnatus) and to Visconti, the statue represented the traveling hero Jason who is described at the start of the first book of the Argonautica as alarming Pelias by wearing, as the Oracle foretold, only one sandal. In the second half of the nineteenth century it was argued that the statue represented Hermes, the messenger of the gods, pausing to receive Zeus's instructions while fastening his sandal. This idea has never met with general acceptance, however, and the statue, or rather the type, is now usually described, Germanically, as the 'sandalbinder'. The move from a specific to a general narrative interpretation is as typical as the move from a Roman to a Greek one."

|

| Nicolas Dorigny Cincinnatus ca. 1704 etching, engraving Philadelphia Museum of Art |

|

| Cincannatus Roman marble copy of an earlier Greek bronze discovered at Hadrian's Villa in 1769 Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek, Copenhagen |

"In 1769 a slightly different version, more broken, but with its original head, was discovered at Hadrian's Villa by Gavin Hamilton. The Pope declined to buy it (although not long afterwards his successor did acquire a smaller, poorly preserved and mediocre version) and so it was sold instead in 1772 to the Marquess of Shelburne (later Earl of Lansdowne). This was much admired, and not surprisingly, a cast of it was presented to the Royal Academy, but even in England throughout the nineteenth century it was the statue at the Louvre, not the one in Lansdowne House, which was discussed by scholars and reproduced by plaster cast merchants. ... Today the Lansdowne version, which was acquired in 1930 by the Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek in Copenhagen, is more famous and more admired than the statue in the Louvre."

|

| Diane de Gabies Roman-era copy of a Greek statue from the 4th century BC formerly in the Villa Borghese since 1820 in the Louvre |

The Villla Borghese statue known as the Diane de Gabies was another late discovery made by the enterprising Gavin Hamilton. He found it on Borghese property at Gabii outside Rome in 1792. It was admired in Rome – but only for about fifteen years – until the not-exactly-voluntary sale of the Borghese marbles to Napoleon. After that, Diane de Gabies joined the caravan on the one-way journey to Paris. The statue has also been called Diana Robing and Diana Succinct.

|

| Jacques-Louis Gautier Diane de Gabies ca. 1855 copy - full-size bronze Royal Collection, Great Britain |

|

| Ferdinand Barbedienne Diane de Gabies ca. 1847 copy - bronze statuette Royal Collection, Great Britain |

|

| Anonymous sculptor Diane de Gabies late 17th century copy - full-size gilded lead Cupola Room, Kensington Palace |

|

| Anonymous sculptor Diane de Gabies 19th century copy - life-size stone archtectural ornament Osborne House, Isle of Wight |

Quoted passages are from Taste and the Antique by Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny (Yale University Press, 1981).