|

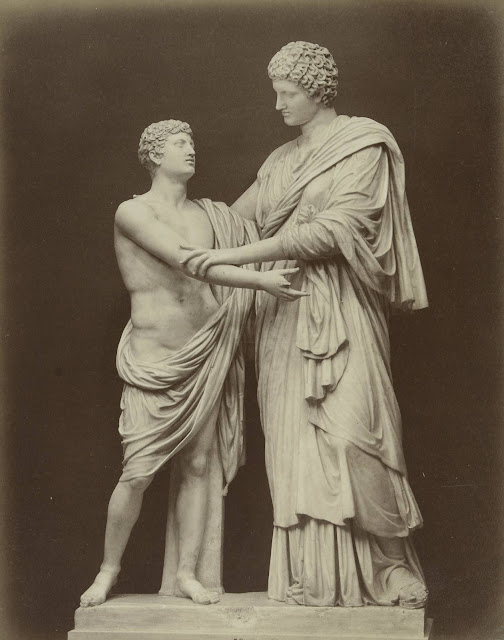

| Anonymous photographer Paetus and Arria at the Museo delle Terme ca. 1880-1904 photograph Rijksmuseum |

The earliest theory described a father killing his daughter and then himself. "This was given more precision by some later seventeenth-century sources which refer to 'Sextus Marius killing his daughter and then himself' – Marius was a wealthy patrician who seeking to protect his daughter from the lust of Tiberius was himself accused of incest with her. However, when the statue was first published (and illustrated) in 1638 it was described as a group of Pyramus and Thisbe, although in Ovid's version of the story Thisbe's suicide followed that of Pyramus (who had killed himself because he thought her dead), which is not the situation in the Ludovisi group. By about 1670 Paetus and Arria had been tentatively proposed as the subject, and although this idea was challenged it remained popular for well over a century. Caecina Paetus was involved in the conspiracy of Camillus Scribonianus in AD 42 and taken to Rome where he was ordered to commit suicide. To encourage him his wife Arria killed herself with the words, made famous in antiquity by an epigram of Martial, 'non dolet ... Patae'. ... Among other ingenious attempts to 'find' the subject, we must mention Maffei's suggestion that it was the loyal euncuh Menofilus killing himself and his charge, the daughter of Mithridates, to save her from dishonor at the hands of victorious Roman soldiers, and Gronovius's cautious suggestion that it was Macareus and Canace, the children of Aeolus forced to kill themselves for their incestuous passion. ... Rather more typical in the eighteenth century was the idea that the subject concerned the conflict of loyalties between family and state. Rossini believed that it showed Fulvius killing himself after his wife had stabbed herself, distraught at the realization that she had disgraced her husband by betraying to Livia the secret opinion of Augustus concerning Tiberius which Fulvius had confided to her. The state was also connected with Roman history in a different way for in the mid-seventeenth century certain marks on the statue were shown as scorchings made by 'the fire that Nero caused to be made for the burning of Rome'.

|

| Jan de Bisschop Paetus and Arria 1668-69 etching Philadelphia Museum of Art |

|

| Domenico de Rossi Paetus and Arria ca. 1704 engraving Philadelphia Museum of Art |

|

| James Anderson Paetus and Arria at the Museo delle Terme ca. 1845-55 albumen silver print Gerry Museum, Los Angeles |

"The subject is now agreed to be a Gaul who stabs himself having already killed his wife to prevent her from falling captive. It was first identified as such by Visconti who supposed that together with the Dying Gladiator it had adorned a monument in Rome erected by some conqueror of the Gauls or Germans such as Caesar or Germanicus. The group is still connected with the Dying Gladiator and is cataloged in Helbig as a copy of the Trajanic or early Antonine period of one of the bronze groups dedicated by Attalos I after his victory over the Gauls in the second half of the third century BC." Among alternative names recorded for this group – Fulvius and his Wife ; Gaul and his Wife ; Macacreus and Canace ; Menofilus and his Charge ; Pyramus and Thisbe ; Sextus Marius.

In the Childe Harold of 1818 Byron devoted two ardent stanzas to The Dying Gladiator (below) – adding his voice to a chorus of 18th and 19th-century adoration. "However, by Byron's time, the theory that the statue represented a gladiator had long been dismissed by scholars, though they admitted that this remained (as it still does) the name by which the figure was generally known." In the same period Ennio Quirino Visconti was arguing that "the physical characteristics of the figure proved that he was a barbarian warrior, either a Gaul or a German, who had presumably died heroically on the battlefield." This belief led him to the idea "that it could have adorned a monument together with the Paetus and Arria" – a view that continues to prevail.

|

| James Anderson Dying Gladiator at the Capitoline Museum ca. 1845-55 albumen silver print Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

|

| Andrea Rossi Dying Gladiator ca. 1780-92 engraving Victoria & Albert Museum |

"Throughout its history the Dying Gladiator has been greeted with universal enthusiasm, and – as was so often the case – a legendary restoration by Michelangelo (of the right arm) added to its fame for some two hundred years. It quickly entered an inner sanctum of the 'musée imagainaire' of educated Europe and it is one of the few statues in our catalog whose reputation remains high. When Giambattista Ludovisi was thinking of selling it in 1670 he valued it at seventy thousand scudi (second only to the ninety thousand he wanted for the two figures of Paetus and Arria and almost twice as much as for anything else in his collection). In 1638 it was reproduced – for the first of countless times – among Perrier's engravings of the finest sculptures in Rome, and when writing up his travel notes many years after his visit to Italy in 1644-45 Evelyn claimed that the Gladiator was 'so much followed by all the rare Artists, as the many Copies and Statues testifie, now almost dispers'd through all Europe, both in stone & metall'."

The bronze Dying Gladiator statuette (below) is a reduced copy of a full-size marble copy of the original Roman statue (also called Dying Gaul, Roman Gladiator, Wounded Gladiator, Myrmillo Dying). The full-size marble copy by Michel Monier was made in 1684 for Louis XIV and installed at Versailles. The statuette itself was acquired in 1811 by Lord Yarmouth acting for the Prince Regent, who placed it in the King's Lodge at Windsor. .

|

| after Michel Monier Dying Gladiator 18th century copy - bronze statuette Royal Collection, Great Britain |

|

| after Michel Monier Dying Gladiator 18th century copy - bronze statuette Royal Collection, Great Britain |

Like the two sculptures above, the group known as The Papirius (below) was part of the Ludovisi collection, housed in the family palace on the Pincio from the 17th through the 19th centuries. These marbles were purchased all together at one swoop by the nation in the 1880s. The Papirius – like the Paetus and Arria – featured in many rival stories that attempted to account for the significance of the figures. The taller one was at first supposed to be male, and the statue thought to represent 'friendship' or 'fraternal greeting'. "By 1704, however, some people were already giving it the name of Papirius by which it came to be generally known: the reference was to a comic anecdote describing the ingenuity with which the young Papirius, nicknamed Paretextatus, had, in the early days of Rome when sons were allowed to accompany their fathers to the Senate, fobbed off his mother's curiosity about what had been discussed there by telling her that the debate had centered on the issue as to whether it was better for the State for one man to have two wives or one woman two husbands."

|

| Anonymous photographer Papirius ca. 1880-1904 photograph Rijksmuseum |

|

| Francesco Piranesi Papirius 1783 engraving British Museum |

|

| James Anderson Papirius ca. 1845-55 albumen silver print Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

"Some writers suggested Penelope and her son Telemachus or Aethra and her son Theseus, and in 1854 Otto Jahn published the last theory to enjoy a long life outside scholarly circles: the group represented Merope and her son Aeptus (whose story had been told in a lost play of Euripides) and it was a particularly dramatic moment of sudden recognition of the son by the mother that was portrayed. More original was the reaction of Herder, who saw in the group a purely general theme: the relationship of the figures provided poignant proof of the power of immobile sculpture to convey feelings of quiet and mutual trust between friends, lovers or members of a family; and indeed to many modern scholars it has seemed that no more specific narrative is intended than is to be found on Attic grave stele (from which the Ludovisi group appears to be derived) showing couples solemnly greeting each other, or bidding farewell."

The Castor and Pollux (below) was also in the Ludovisi collection, but its fate was exceptional. In 1678 it was acquired by Queen Christina of Sweden, resident in Rome. She retained it for her lifetime. "It was bequeathed with the rest of her collection to Cardinal Azzolini who died a few weeks after she did and whose heir, Marchese Pompeo Azzolini, sold most of its contents." The Castor and Pollux passed through several hands until 1724, when it was purchased by Philip V of Spain and shipped to Madrid. "It is ironic that the group should have left Rome, for Carlo Maratta had energetically encouraged Queen Christina to acquire it in order to keep it in the city."

|

| Castor and Pollux Marble sculpture of the first century BC sold to the Spanish King in 1724 Prado |

|

| Joseph Nollekens Castor and Pollux 1767 full-size marble copy - based on a plaster cast Victoria & Albert Musseum |

|

| Domenico de Rossi Castor and Pollux ca. 1704 etching, engraving Philadelphia Museum of Art |

|

| William Hilton Castor and Pollux ca. 1801-1839 drawing British Museum |

"The Castor and Pollux was during the early nineteenth century particularly popular in Germany. A cast features very prominently in Martens's view of the Charlottenburg cast gallery of 1824; a bronzed cast may still be seen in Goethe's house, and there are bronze copies at Weimar and Potsdam. The sculptor Friedrich Tieck suggested that the group represented Antinous with the Genius of Hadrian. This idea was elaborated by leading German scholars in a variety of ways. ... Nonetheless, there is no agreement as to the subject of what is now recognized as an extensively restored group." Some of the other names in use have included – The Decii ; Odescalchi Dioscuri ; Two Genii ; The San Ildefonso Group ; Two Lares ; Orestes and Pylades ; La Paix des Grecs.