|

| Underwood and Underwood, Publishers Ancient marbles int he Tribuna of the Uffizi, Florence ca. 1900 stereograph Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

This stereograph view of the Tribuna was made about 1900. It recorded three of the large antique statues that had occupied the same spaces in the same small red room for more than two hundred years. A pair of sculptures – matching in their compactness – flanked the Venus de' Medici. To the left were (and are) the Wrestlers – to the right, the Arrotino, or, Knife-Sharpener.

|

| The Wrestlers Roman marble copy of an earlier Hellenistic bronze group as displayed in the Tribuna |

|

| Fratelli Aliinari The Wrestlers ca. 1880-95 albumen silver print Rijksmuseum |

|

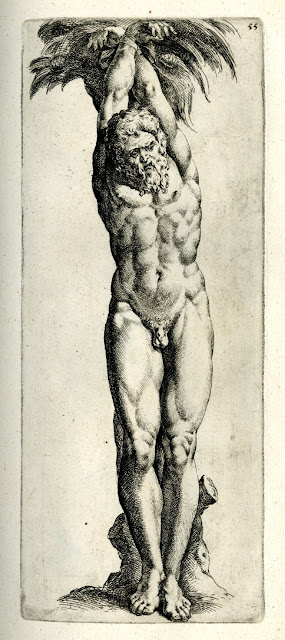

| Domenico de Rossi The Wrestlers ca. 1704 etching, engraving Philadelphia Museum of Art |

|

| Jan de Bisschop The Wrestlers ca. 1668 engraving Rijksmuseum |

|

| Jan de Bisschop The Wrestlers 1671 etching Philadelphia Museum of Art |

The core of the Wrestlers group was excavated in Rome in 1583. It belonged to the Medici by 1594 (following a restoration that included new arms, new legs, and new heads (though one of the new heads was also antique, from a different source)). These marbles have also been known as the Antique Boxers, Grecian Boxers, Gladiators, La Lotta, Lottatori, and Roman Wrestlers.

The Arrotino (below) is documented from the 1530s, owned privately by Roman collectors. It came into Medici possession by purchase in 1578. "This very widely admired statue was invariably included in both luxurious and popular anthologies of reproductions and noted with enthusiasm by travelers to Rome, and later to Florence. In 1684 it was copied for Versailles by Foggini. In 1871 this copy was removed to the Tuileries and replaced, above the steps leading to the Parterre Nord, by a bronze which had been cast by the Kellers in 1688 – it is there paired with one of the Crouching Venus. Soldani made a bronze (with three other famous statues in the Tribuna) for the Duke of Marlborough in about 1710 which is still at Blenheim; there was a cast of the 'Schleifer' in the Antikensaal at Mannheim which was opened in 1787; and Jefferson included a copy of the 'Roman slave whetting his knife' along with twelve other celebrated sculptures (then known to him only through prints and descriptions) among those which he wished to acquire for his projected art gallery at Monticello."

|

| Francesco Piranesi The Arrotino 1783 engraving British Museum |

|

| Anonymous sculptor The Arrotino late 18th century copy - bronze statuette Royal Collection, Great Britain |

"The earliest references describe the figure in the most neutral terms: 'a knife sharpener', a 'villano' (peasant), etc. Many people stuck to this simple nomenclature, sometimes with slight embellishments, and indeed the name most commonly adopted toward the end of the seventeenth century was (and still remains) that of 'Arrotino' (knife grinder). But either the expression of the figure itself or a belief that all statues must represent some specific individual very quickly encouraged scholars and connoisseurs to search for a more satisfying designation, and as the alternatives multiplied, so too did admiration for the convincing manner in which the chosen subject had been portrayed. Like other figures (such as the Spinario and the Cincinnatus) the Arrotino was recruited into the ranks of those heroes, sometimes anonymous but sometimes with names recorded in classical texts, who had deserved well of ancient Rome and had – it was supposed – been rewarded with a statue. In 1594 Cavalleriis identified the figure as 'Manlius Capitoli propugnator' (the Marcus Manlius whose sleep had been disturbed by the cackling of Rome's sacred geese and who had successfully defended the Capitol against a night attack by the Gauls), but this theory met with no success, as it did not adequately explain what were seen as the three basic characteristics of the statue: the plebeian countenance, the attentive expression and the sharpening of the knife. By the middle of the seventeenth century it was generally accepted that the Arrotino portrayed a serf who, while engaged at his work, was overhearing a plot against the State." Among other names in use at one time or another for the Arrotino were – Attius Navius ; Clown whetting his scythe (or knife) ; Naked Gladiator ; The Grinder ; M. Manlius ; Milichus ; Le Rémouleur ; Il Rotatore ; Listening (or Roman) Slave ; Scythian Slave ; The Spy and The Whetter.

|

| The Arrotino as displayed in the Tribuna |

The Flemish engraving below, based on drawings made by Maarten van Heemskerck in Rome, is one of the earliest surviving records of a Renaissance installation of antique sculpture. It is also the earliest record of the statue portraying the intended victim of the Arrotino. The figure extended along the right edge of the print represents Marsyas, the unfortunate satyr who competed in music with the god Apollo.

|

| Hieronymus Cock after Maarten van Heemskerck Statue Court of the Palazzo della Valle in Rome 1553 engraving British Museum |

In 1584 the statues in this courtyard were sold to the Medici, after the Pope had overruled a testamentary document forbidding such a sale. "With the exception of the three colossal porphyry Captives (which together with one marble one were valued at two thousand ducats) the Marsyas was (at four hundred ducats) the most highly valued of the della Valle antiquities at the time of their purchase by the Medici, and it remained a famous statue, reproduced in major anthologies of prints, and highly praised by both travelers and connoisseurs in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – it seemed 'very singular' to Mortoft; 'exceeding good' to Wright; 'si bella scultura' to Maffei; 'excellent' to Northal. On the other hand although the French Academy had acquired a cast of the statue by December 1684, neither casts nor copies of it were common. They would have been difficult to install appropriately in a domestic or garden setting."

|

| Cherubino Alberti Marsyas 1578 engraving British Museum |

|

| Jan de Bisschop Marsyas ca. 1672 etching British Museum |

|

| Domenico de Rossi Marsyas ca. 1704 engraving Philadelphia Museum of Art |

"General acceptance of the theory that the Arrotino should be grouped with the Marsyas, which was first proposed when both statues were in the Villa Medici, was perhaps delayed partly because they were separated soon afterwards. The Marsyas and the Arrotino have now been cataloged by Mansuelli as copies or derivations of two of the three figures in a bronze group of the Pergamene school showing Apollo ordering a Scythian slave to flay his rival Marsyas."

|

| Anonymous Italian artist Apollo, the Arrotino, Marsyas 16th century drawing British Museum |

Quoted passages are from Taste and the Antique by Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny (Yale University Press, 1981).