|

| Edmund Thomas Parris Standing Model ca. 1840-50 drawing Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

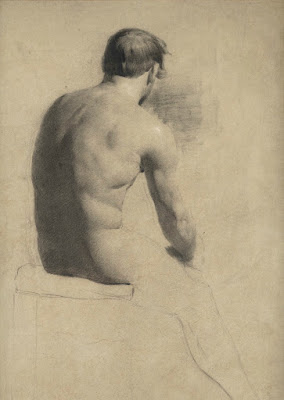

| Edmund Thomas Parris Seated Model 1847 drawing Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| William Quiller Orchardson Seated Model ca. 1845-55 drawing Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| William Quiller Orchardson Seated Model ca. 1845-55 drawing Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| William Etty Seated Model ca. 1820-40 oil on card, mounted on canvas Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| William Mulready Standing Model 1859 drawing Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Henry Hugh Armstead Bending Model ca. 1875 drawing Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Henry Hugh Armstead Recumbent Model ca. 1880 drawing Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Henry Hugh Armstead Standing Model ca. 1858-62 drawing (study for sculptural relief) Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Henry Hugh Armstead Model wielding Spear 1870 drawing (study for a medal for engineers) Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Alfred Ansell Prize Drawing - Life Class 1886 drawing Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Edward Poynter Gesturing Figure 1872 drawing (study for fresco) Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Edward Poynter Seated Figure 1872 drawing (study for fresco) Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Edward Poynter Seated Figure 1872 drawing (study for fresco) Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Edward Poynter Figure of Stone-Thrower 1872 drawing (study for fresco) Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| F. Ernest Jackson Life Study Sketch ca. 1920 drawing Royal Academy of Arts, London |

|

| Russell Westwood Students modelling Figures from Life at the Royal Academy Schools 1953 photograph Royal Academy of Arts, London |

The Adult Section

When I was 11 and the librarian finally let me in to browse alone,

showing me where the light switches were for each stack

and teaching me a few things about call numbers,

and teaching me a few things about call numbers,

at first I walked on tiptoe, afraid

those huge stern books, in their huge stern leather bindings,

those huge stern books, in their huge stern leather bindings,

The Collected Works of Horace Walpole, for instance,

and The English Poets: Selections,

with Critical Introductions by Various Writers

and a General Introduction by Matthew Arnold,

edited by Thomas Humphrey, M.A.,

Late Fellow of Brasenose College, Oxford,

were going to tumble over onto me

and literally kill me with the weight of their knowledge,

especially The Proceedings of the New York State Geographical Society,

and literally kill me with the weight of their knowledge,

especially The Proceedings of the New York State Geographical Society,

in its gigantic volumes up to 1947,

each big enough to crush two babies with one blow,

and complete in one volume apiece The Works of Byron and Tennyson

with plentiful illustrations – books so heavy you had to deal with them

as if you were lifting a small boulder from an English brook,

walking them spread-kneed to the round mahogany reading table,

as if you were lifting a small boulder from an English brook,

walking them spread-kneed to the round mahogany reading table,

which was four times the size of any dining room table I'd ever seen,

and ten times as imposing, especially if some adult sat ghastly there.

Then you'd heave the books up under one of the six reading table lamps,

beneath which dangled straight down

tarnished bronze chaincords. I should add, for the pleasure of the image,

that whoever, long ago, had replaced the original oil lamps,

had ordered the chains much too long, so that each excess lay in a puddle,

like the coils of an Indian fakir's rope trick. . . . Alone,

at 11 years old, in the adult section of the Round Lake Public Library,

I first began to feel all those strange names floating around me in the semi-dark,

all those angels, will o' the wisps, great swooping birds, doves,

ravens, raptors: Kant, Hegel, Saintsbury, Schopenhauer,

Catullus, Swedenborg, Pliny the Elder,

Cervantes, Alexis de Tocqueville, Willa Cather,

St. Augustine, Seneca, Toynbee, Charlotte Brontë,

Racine, Stendhal, Goethe, Dostoyevsky,

and I knew what they said about old library books was true.

They whisper,

seek wisdom, seek wisdom, seek wisdom, seek wisdom, seek wisdom

repeated so often the words begin to ebb and flow inside you,

compelling you to read until your eyes fall out. . . . The librarian,

a kind elderly woman who wore her glasses on a chain

as librarians did then, long before it became the fashion,

would call me out of the stacks, or away from that reading table

ten minutes before closing time, and I'd emerge

blinking under the arabesque light of the small chandelier,

to stand before the checkout desk, lugging six volumes – the limit

for children allowed in the adult section –

and "Are you sure you can handle this?" she'd murmur,

hefting a Plato's Republic or Plays by Oliver Goldsmith,

or Lysistrata (that one I snuck past her!)

to which I'd say, "I think so, ma'am," being at that time

under the common illusion that librarians, especially elderly ones,

had read – as part of their job – every single book in the library.

At last the stamp would go stamp stamp six times,

sometimes her wrist slightly rocking

if she'd clobbered the take out slip too lightly at first,

and I'd be out the door, walking slowly,

past the gargoyle fountain, under the huge old pines,

frightened, elated, sometimes trembling,

sure that the weight of the world had come into my arms,

ready to learn what it was that I should do.

– Dick Allen (2002)