|

| Titian The Annunciation ca. 1520 oil on panel Cappella Malchiostro, Duomo di Treviso |

|

| Titian The Annunciation ca. 1520 oil on panel (installation view) Cappella Malchiostro, Duomo di Treviso |

"No closely subsequent commission of a religious painting offered Titian the opportunities or the demands of the Assunta. Three major altarpieces came from him in the neighbourhood of 1520, and while each is a demonstration of Titian's matured mastery, none is so inclusive as the Assunta of his whole range of artistic resource. Each one, indeed, appears to stress a different facet of the possibilities he had set out in the Frari altar, and to explore it more particularly than there. The Annunciation, the altar of the Malchiostro Chapel in the cathedral of Treviso, is probably contemporary with the fresco decoration there by Pordenone. In the altar Titian probes in the direction of illusionism with extreme boldness. He turns the accustomed lateral arrangement of this theme into a penetration of perspective depth, and its normal balance into a compensated asymmetry. In situ, the effect of a dynamic continuity from the viewer's space is absolute, but it is not baroque; the space we penetrate and what inhabits it give too explicit evidence of ideal order."

|

| Titian Madonna and Child in Glory with St Francis of Assisi and St Blaise (Gozzi Altarpiece) 1520 oil on panel Pinacoteca Civica Francesco Podesti, Ancona |

"The Gozzi Altar at Ancona (Museo Civico, dated 1520) searches in a different sense, making a major factor of what had been a secondary one in the Assunta. The Ancona painting is a mobile and equilibrated order, but this is not its main point. Unlike the Assunta, and unlike the Treviso altar also, it is made out of manipulations of effects of light, not of substances or measurings of space. The whole apprehension of experience and the means of painting it reassert the optical predisposition within Titian's art, somewhat obscured recently by his classicizing search for form. The reassertion is not merely retrospective: it is an exploring of a new degree of visual sensibility, and, more important, of the ways in which the classical end of mobile harmony can be attained by manipulations less of form than of coloured light. This direction is explicitly opposed to that of Central Italian classicism, yet the Ancona altar offers a provable instance of Titian's response to the dissemination in prints of Central Italian examples for he has based his Madonna in placing (and somewhat in pose) on Raphael's Madonna di Foligno."

|

| Raphael Madonna di Foligno ca. 1511-12 tempera on panel Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome |

|

| Titian The Resurrection (Averoldo Polyptych) 1520-22 oil on panels Chiesa dei Santi Nazaro e Celso, Brescia |

|

| Titian The Resurrection (Averoldo Polyptych) 1520-22 oil on panels (installation view) Chiesa dei Santi Nazaro e Celso, Brescia |

|

| Titian The Resurrection (detail) St Nazarius, St Celsus, and Donor (Averoldo Polyptych) 1520-22 oil on panel Chiesa dei Santi Nazaro e Celso, Brescia |

|

| Titian The Resurrection (detail) Annunciatory Angel (Averoldo Polyptych) 1520-22 oil on panel Chiesa dei Santi Nazaro e Celso, Brescia |

|

| Titian The Resurrection (detail) Virgin Annunciate (Averoldo Polyptych) 1520-22 oil on panel Chiesa dei Santi Nazaro e Celso, Brescia |

|

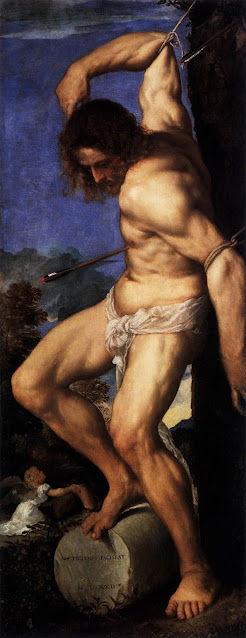

| Titian The Resurrection (detail) St Sebastian (Averoldo Polyptych) 1520-22 oil on panel Chiesa dei Santi Nazaro e Celso, Brescia |

|

| Michelangelo Struggling Slave 1513 plaster cast of Louvre marble Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Rio de Janeiro |

|

| Titian Worship of Venus 1518-19 oil on canvas Museo del Prado, Madrid |

|

| Titian Bacchanal of the Andrians (People of Andros) ca. 1520-21 oil on canvas Museo del Prado, Madrid |

|

| Titian Bacchus and Ariadne 1522 oil on canvas National Gallery, London |

"Titian's exposure to Central Italian example in the Ancona and Averoldo altars was by the indirect means of reproductions; but there were two instances at least, not long preceding these, when his contact with examples of Central Italian classicism must have been immediate. In November 1519 he travelled (in the company of Dosso Dossi) from Ferrara, where he was temporarily in residence, to Mantua, and almost certainly encountered the (right) half of Michelangelo's mutilated Cascina cartoon, which had emigrated to Mantua from Florence probably a little earlier. It is not only the effect of the cast of the Bound Slave but the after-trauma of this experience that seems evident in the altarpiece for Brescia; and the cartoon also left its clear mark on the Andrians, which Titian had in hand for Alfonso of Ferrara at the same time."

"It was the delivery of the first of this set of pictures for Alfonso's camerino, the Worship of Venus (Madrid, Prado), that had brought Titian to Ferrara in 1519, and in that picture there is the indication of another contact with a Florentine example, quite unlike Michelangelo's. In 1517 Alfonso had asked Raphael, without success, for a picture for his camerino, but he had apparently been able to secure the cooperation of Fra Bartolommeo: a drawing by him for the Worship of Venus – an exceptional enough theme for the Frate's interests – survives in the Uffizi. There is no doubt that it came into Titian's hands when, after Fra Bartolommeo's death late in 1517, Titian was chosen to replace him in the commission. The Frate's drawing is in his freest late vein, broad in form and deep in chiaroscuro, and full of energy of action. In almost all respects Bartolommeo's expression of his developed Florentine classical style accords with Titian's style of the moment – of course, Titian's sympathy with Bartolommeo's drawing is more than he would have demonstrated had the Frate's model been a painting. In his picture Titian adapts Bartolommeo's main motifs for the figures, and his temper of interpretation of the theme seems inspired by the Frate. Beyond this, Titian diverges from the Florentine exemplar into pure Venetian. He insists upon a major place for landscape in his composition and an exploration in depth of the landscape space; and this insistence is not separable from the inspiration that has caused him to shift the Florentine design into diagonal asymmetry, turning Bartolommeo's structure into profile and displacing its main axis to the side. The structural results resemble those in the near-contemporary Annunciation of Treviso, making a higher energy form and intensified illusion. Here, however, where the physical context of the picture does not suggest illusionistic stress, and there are no rigid forms of architecture in the painted space to measure the progression into depth, the relation between space and picture surface is quite different. The shapes and colours of the landscape describe depth, but they are manipulated at the same time into a pattern that relates to the design on the picture surface, muting the recession, compensating the asymmetry of composition, and – almost most important – suggesting an effect of interwoven continuity of visual texture. Part of the intention of the asymmetric structure is to avoid the look of artifice, and convey the sense of a more casual and thus more actual existence. This intention is realized, but on the basis of the most sophisticated contrivances to make classical unity in equilibrium that Titian has so far achieved."

"Like the Sacred and Profane Love a few years earlier, the Worship of Venus celebrates a beautified sensuous existence, but the fluency and fullness with which Titian makes his statement here exalt its meaning towards a higher ideality. The sense of beauty of existence has become lyric, but vibrant and immediate in its poetry, not distant, as the lyricism of Giorgione had been. This immediacy is an index not only of Titian's response but of that of Venetian art in general to the literary matter of antiquity. It was no impediment to the translation of antique myths into the warmest actuality that the programme for Titian's contribution to Alfonso's camerino was as archaeological as any that might be devised in contemporary Rome. The Worship of Venus was intended to re-create a picture described in detail by Philostratus the Elder in his Imagines as existing in a house near Naples, and the second work supplied by Titian for the camerino, the People of Andros [Bacchanal of the Andrians] (Madrid, Prado, c. 1520-1), was based on another extensive literary description in the same source; in both cases Titian illustrated the given text with unusual fidelity. The last of Titian's set, the Bacchus and Ariadne (London, National Gallery, 1522), follows, also quite literally, a text in Catullus (Carm. LXIV). There is a corresponding visual antiquarianism that Titian exercises in these paintings, making more quotations from antique statuary than he ever had occasion to before, and there is a reinforced attention to what he had been able to learn of the classicism of the Central Italian school. The Andrians post-dates Titian's Mantuan visit of November 1519, for it is specific in its derivation, and others seem to have been less literally derived. More important, the very mode of Titian's complex figure composition, without precedent in his own art, is a consequence of his experience of the Cascina fragment. The Bacchus and Ariadne extends this new-learned mode of ordering the figures, and in addition (exactly as in the contemporary Averoldo Altar) gives prominent place to types based on the Laocoön and on Michelangelo's Bound Slave."