|

| Titian Madonna of the Pesaro Family ca. 1519-26 oil on canvas (altarpiece) Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice |

"The Madonna of the Pesaro Family (Venice, Frari) is the counterpart in religious painting of Titian's accomplishment in the Este Bacchanales, and its time of creation was coextensive with them. It was commissioned in 1519 and finally set up only in 1526, but its likely time of design is towards the earlier date and its most concentrated moment of execution probably about 1522. Differently accessible to inspection from Titian's prior grandiose apsidal altar in the same church, the Assunta, the first effect the Pesaro altar makes is that of the absolute efficiency, so great it needs no show of virtuosity, that Titian's technique for describing nature has attained. He evokes the persons, the setting of architecture, and their ambient atmosphere into a new order of credibility. Naturalism is so obvious a factor of the Venetian classical style that we tend to overlook its role, and it requires a demonstration like this one to recall the function and the magnitude of such descriptive power, though in this degree it is Titian's alone."

|

| Titian The Entombment ca. 1525 oil on canvas Musée du Louvre |

"About 1525, the Entombment (Paris, Louvre) is another and still higher aspect of the same intentions that informed the Pesaro Madonna. With a sophistication of visual sensibility like that which he had come to in the two later Este Bacchanales, and with a control of hand that seems even to exceed what was in them, Titian makes absolute synthesis in the Entombment between optical verity and effects of art. He describes existences in light with the truth of an illusion, yet the illusion is not only of the seen thing, but of the seen thing manipulated to make strengths, mutings, and consonances that are not truth but invention. It is also invention that shapes the movement of the actors, giving them a styled grace and deliberating their connexion in a rhythmic accord. They are set close to us, and the strength of colour in them intensifies their sense of nearness; but even as this closeness presses the effect of verity, there is no desire to give the image the relation to us of an actual illusion. The painting's contents, its colours especially, verge towards the picture plane or adhere to it, emphasizing the explicitly pictorial identity of the work: the principle is identical with one we have observed in examples of the highest classical painting style of Central Italy, but it functions still more patently when the primary pictorial matter is colour. As Titian finds a new reach of his powers of description he accompanies it with a development of means that at the same time reaffirm the ideal and synthetic value of the work of art."

|

| Titian St Christopher ca. 1523 fresco Palazzo Ducale, Venice |

"About 1523, perhaps following on the Este Bacchus and Ariadne, Titian painted a St Christopher fresco (Venice, Palazzo Ducale; about twice life-size) in which the Laocoön and Michelangelo's Bound Slave were again (as in the Bacchus picture and the Averoldo Altar) a challenge and a source, provoking more overtly than before a demonstration of the energies the painter can extract from plastic form. Titian exceeds his models, moving the gigantic figure of the Saint with an impetuosity that recalls the pictures of his earliest years, and intensifying the sense of activity of substance by the vibrance of description he makes with his painter's brush."

|

| Titian Death of St Peter Martyr ca. 1528-30 oil on canvas (copy by Johann Carl Loth, 1691) Basilica di Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Venice |

|

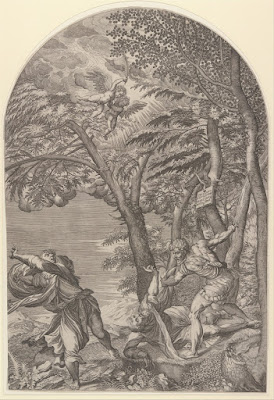

| Titian Death of St Peter Martyr ca. 1528-30 (engraving by Martino Rota, ca. 1560) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Titian Death of St Peter Martyr ca. 1528-30 (chiaroscuro woodcut by John Baptist Jackson, ca. 1738) National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

|

| Pordenone (Giovanni Antonio Licinio) Death of St Peter Martyr ca. 1526-27 drawing (compositional study) Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

|

| Pordenone (Giovanni Antonio Licinio) Death of St Peter Martyr ca. 1526-27 drawing (compositional study) Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

"The aesthetic problem in the St Christopher was joined some time later to a theme of authentically dramatic action. At an undetermined date between 1525 and 1527 a competition was held for an altar painting of the Death of St Peter Martyr in SS. Giovanni e Paolo: Titian won the contest, and in 1528-30 executed the painting (now lost, and replaced by a copy). Titian's rivals were Palma and Pordenone. Palma was no challenge, but Pordenone was, and in terms that presented to Titian the same problem of a plastic style that he had faced recurrently since his indirect encounter with the Laocoön and Michelangelo. In addition, Pordenone was the exponent of the most extreme dramatic manner in contemporary art. Apparently thinking of Venetian taste, Pordenone moderated his accustomed violence in his design; but apparently thinking of his competitor, Titian conceived the most radical invention he could make, exceeding Pordenone's precedents in dramatic force, in urgency of action, and in assertion of energy of forms expanding in their space. Articulate in form and in expression as Pordenone could not be, and far surpassing him in his descriptive means, in this picture Titian generated a vastly higher and more trenchant power. The design in which the figures act conveys the sense of an explosion: behind the figures tree-trunks act almost anthropomorphically to extend and elaborate this effect. The violence of emotion, the intensity of action, and the expansiveness of pattern are in a degree which, at least as much as in Pordenone's or Correggio's extreme inventions, suggests the temper of a baroque style. Yet, more evidently than in them, the effect pertains to classicism. The mode of feeling of the figures is refined toward typology, and their actions have the structured grace of classical dramatic repertory; their ordering is in a scheme of counterpoise. In the setting, the explosive impetus of design is tempered as it rises, then muted, then diffused into a lyrical and tragic light. Rather than a foretaste of a baroque style, the St Peter altar is a counterpart, in Venetian terms, of that magnitude of classical dramatic mode which Raphael had reached a decade and a half before in his Stanza d'Eliodoro."

|

| Titian- Madonna of the Rabbit (Vierge au Lapin) ca. 1530 oil on canvas Musée du Louvre |

|

| Titian- Aldobrandini Madonna (Marriage of St Catherine) ca. 1530 oil on canvas National Gallery, London |

"By 1530 Titian's position in respect to the resources of the classical style was one of absolute command: he could work any possibility that they contained or any permutation of them at will and with total mastery. There are two remarkable demonstrations of about this date, in smaller-scale devotional pictures, in which he exploits this fluency to give an effect of life so facile and apparently so casual that it seems that recognizable classical conventions have no part in them: these are the Vierge au Lapin (Paris, Louvre, probably done for Federigo Gonzaga of Mantua) and the Marriage of St Catherine (London, National Gallery). In them Titian evokes schemes of compositional asymmetry which he had invented earlier and (as if in compensation for his Romanist and plastic preoccupation in the Peter Martyr altar) a purely optical painting mode; he recalls the mood and setting of his former Giorgionismo. All these, however, are developed with his present measure of sophistication. The air of accident in these images is the surface of a brilliant and finely deliberated manipulation of design in structure and in colour: these might be demonstrations of a classicist's conception of the virtue of sprezzatura. They extend into a new degree of freedom the principle (earlier substantially demonstrated in the Andrians) of a charged harmony and a unity of pictorial texture made from shapes and colours set in movement. These pictures in one sense that is peculiarly Venetian, and the St Peter Martyr altar in another that is less explicitly native, mark the extreme points so far in Titian's extension of the possibilities of the classical painting style. For him, as for the painters who had participated in a more revolutionary way in the ferment of the 1520s, the new decade initiated a phase of détente. For a time the temper of Titian's art became contrastingly conservative, not just declining further new experiment but seeming to seek reaffirmation of old principles, or of the virtues of a safer, less experimental classicism."

|

| Titian Presentation of the Virgin 1534-38 oil on canvas Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice |

|

| Titian Madonna in Glory with Six Saints (Madonna dei Frari) ca. 1535 oil on panel, transferred to canvas Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome |

|

| Titian Pardo Venus (Jupiter and Antiope) ca. 1535-40 oil on canvas Musée du Louvre |

"Between 1534 and 1538 [Titian] executed a major large-scale commission, the Presentation of the Virgin, for the Scuola della Carità (Venice, Accademia) and chose to interpret it in the quattrocentesque tradition of Venetian teleri, only unassertively modernizing the rectilinear perspective order of those archaic examples, and enlarging – with his by now unsurpassable technique – their emphasis on descriptive naturalism. About the middle years of the decade, he painted a monumental altar of the Madonna in Glory with Six Saints for S. Niccolò dei Frari (Rome, Vatican) in which he emphasized, again with almost rectilinear effect, clarity of structure and heavy dignity of form. A large-scale mythology, the so-called Pardo Venus (Paris, Louvre), was probably in substance an invention of the late 1530s, though significantly reworked later; it is full of motifs and ideas that have been recollected from an earlier and more Giorgionesque time, ordered in an obvious and uncomplicated classicizing scheme."

|

| Titian Venus of Urbino 1538 oil on canvas Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

"The summation of this major vein in Titan's art in the fourth decade is the Venus of Urbino (Florence, Uffizi) – the painting of a 'donna nuda' to which the patron, Guidobaldo, Duke of Camerino (only later of Urbino), referred in a letter to Titian of 1538 – poised with wonderful effrontery on the border between portraiture and mythology, and between erotic illustration and high art. The mode of design in this painting is a sophisticated archaism, resurrecting not only Titian's own compositional schemes of his phase closest to Giorgione but obviously also Giorgione himself (and even recalling the perspective-based designs of Bellini). The patent reference to Giorgione underlines how Titian has transposed the distanced dream of Giorgione's Venus into a present prose. In its mondanity Titian's treatment of the subject is completely modern; at the same time it reasserts the oldest strain in Titian's art, the realist substratum that is in his pictures of the second decade, which persisted there as an inheritance from Bellini. What there is of ideal beauty in the Venus of Urbino is not more than the cosmeticizing process that had been applied to the women of the Sacred and Profane Love, or to the subjects of the half-length allegories of that time. The last had been more covert advertisements than the Venus for the same conspicuous product of the opulent Venetian economy: negotiable female beauty. But what is not in the earlier thematic analogues is the painting of this image with Tian's present powers of eye and hand. The mastery of touch that summons the figure to existence and evokes its vibrance – muted for the moment – of sensuality is the hand's recording of a power of generalizing of sensuous experience that resides in the mind. This is what, despite the atmosphere of illustration in the Venus, conveys its counterweight, an authentic sense of ideality."