|

| Barthel Beham The Miser and the Stillbirth ca. 1528-32 engraving British Museum |

"Even for a period that was obsessed with representations of death, Barthel's uncompromising image is deeply idiosyncratic. Although its tone is primarily one of admonition, there is almost a note of consolation to grieving parents in this representation of the moralising Old Testament text (from Ecclesiastes 6: 'The wise man says that an untimely birth is better than the miser who does not enjoy his wealth'). Sixteenth-century life was harsh and infant deaths were common: Dürer was one of eighteen siblings, only three of whom attained adulthood, and it has been estimated overall that at least one third of all children of this period died before the age of five."

– curator's notes from the British Museum

|

| Barthel Beham Child sleeping on skull 1525 engraving British Museum |

|

| Barthel Beham Four skulls and dead child with hourglass ca. 1528-30 engraving British Museum |

|

| Barthel Beham Three skulls and dead child with hourglass 1529 engraving British Museum |

|

| Barthel Beham Mother and dead child with skull and hourglass ca. 1528-30 engraving British Museum |

"This engraving of a mother attempting to nurse an apparently dead child, with a skull and hourglass nearby, is a variation on Barthel's theme of death represented by the contrast of a skull and a child. On this occasion, an Italianate setting is deliberately invoked. The interior scene with a view through a window is an Italian format which Dürer used in his compositions. The woman's costume is reminiscent of Venetian fashion, and, as Waldmann noted, the building seen through the window resembles the tomb of Theodoric at Ravenna. The message of Barthel's print is made obvious without an inscription, but a circular lead plaquette by Lorenz Rosenbaum (died c. 1564) based on Barthel's design without the background is inscribed, 'Hodie mihi, cras tibi' ('today me, tomorrow you') to emphasize the 'memento mori'."

– curator's notes from the British Museum

|

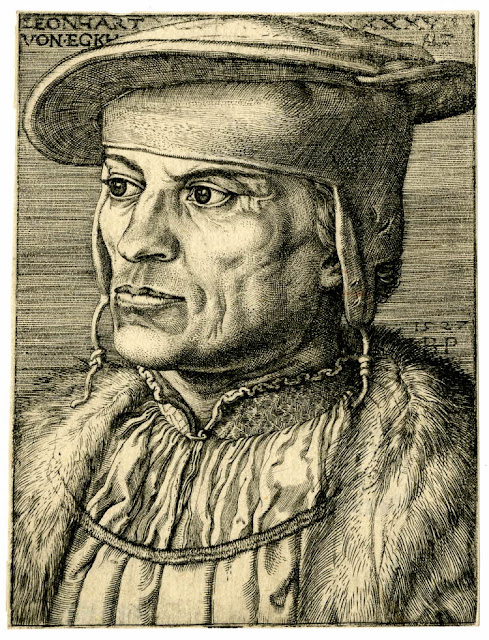

| Barthel Beham Portrait of Leonhard von Eck engraving 1527 British Museum |

|

| Barthel Beham Portrait of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor 1531 engraving British Museum |

|

| Barthel Beham Portrait of Ferdinand, King of the Romans 1531 engraving British Museum |

|

| Barthel Beham Portrait of Duke Ludwig X of Bavaria 1532 engraving British Museum |

|

| Barthel Beham Eve passing apple to Adam ca. 1520-40 engraving British Museum |

"The unusual and macabre transformation of the Tree of Life into a visual Tree of Death is the most striking element of Barthel's composition. The pessimistic view of mankind, inherent in all representations of the Fall, is here taken to a bizarre extreme. Representations of Death in association with human sexuality are so common in prints of this period that it is not surprising to see this traditional Old Testament theme, in which the serpent is associated with the sin of lust, interpreted in such fashion for collectors of small engravings."

– curator's notes from the British Museum

|

| Barthel Beham Cleopatra with asp ca. 1520-24 engraving British Museum |

|

| Barthel Beham Lucretia standing in niche ca. 1520-40 engraving British Museum |

|

| Barthel Beham Woman seated on cuirass and holding mirror (Allegory of Prudence) ca. 1520-40 engraving British Museum |

|

| Barthel Beham Winged Genius flying on globe 1520 engraving British Museum |

"This is one of eleven recorded engravings dated 1520, when Barthel was only eighteen years of age. They all bear witness to his precocious talent, and this engraving in particular is remarkable for its technical accomplishment and originality of composition. The idea of the Genius, a spirit of the air who transmitted divine messages to people in the form of premonitions and dreams, was common in antiquity and incorporated into Christian thought during the twelfth century. The connection of the Genius with the concept of luck explains the existence of the globe, which is a common attribute of figures of Fortune, as is the walking stick which Barthel's figure holds. Small winged children or genii with these attributes appear in Dürer's work on the ground, but Barthel's innovation is the representation of such a figure in flight as the main subject of a print. The swirling engraved lines he has used to evoke atmosphere and the delicacy of the stippling in the landscape underneath demonstrate his fluent command of the technique. Figures who represent Genius with the ability to tell the future also appear in the work of the Nuremberg poet Hans Sachs, who collaborated on occasion with the Beham brothers. In two different poems, he described figures of Genius who appear in dreams to young men, one of whom is borne aloft and flown over a landscape devastated by war."

– curator's notes from the British Museum