|

| Simon Vouet Head of Endymion before 1649 drawing (study for painting) Musée du Louvre |

|

| Pierre Puvis de Chavannes Head of a Woman ca. 1880 drawing Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

|

| Bernard Picart Head of a Woman before 1733 drawing Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

| Charles-Joseph Natoire Head of an Angel ca. 1755 drawing (study for painting) Musée du Louvre |

|

| School of Fontainebleau Head of a Woman 16th century drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| School of Fontainebleau Head of a Woman 16th century drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

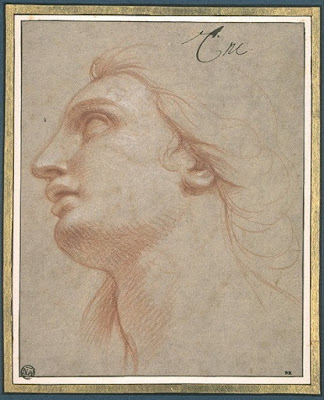

| Michel Corneille the Younger Head of the Virgin ca. 1660-70 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Louis Boullogne the Younger Head of a Woman ca. 1713-15 drawing (study for painting) Musée du Louvre |

|

| Anonymous French Artist Head of a Barbarian from Trajan's Column, Rome 18th century drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Anonymous French Artist Head of a Youth 18th century drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Anonymous French Artist Head of a Man 18th century drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Charles Le Brun Head of a Woman ca. 1670 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Charles Le Brun Head of a Soldier ca. 1685 drawing (study for painting, The Raising of the Cross) Musée du Louvre |

|

| Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié Head of a Youth before 1784 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié Head of a Woman with an Earring before 1784 drawing Musée du Louvre |

"When we ask what is beautiful, we do not mean to speak of an object which exists outside us and is separate from other objects, as when we ask what is a horse or what is a tree. A tree is a tree and a horse is a horse absolutely and in themselves, there is no need to compare them with any of the other things contained in the universe. This is not the case with beauty. This term is not absolute but expresses a relation between the objects we call beautiful and our ideas, or our feelings, or our understanding, or our heart, or, finally, other objects different from ourselves."

"Some speculative thinkers, accustomed to judging objects coolly and from ideas only, count feelings for nothing and consider all that is built upon them and all that follows from them as capricious or wayward. In contrast others, who are more numerous, do not reason at all, or hardly at all, and deliver themselves over entirely to their feelings. Since these latter are unable to trace the origins of their feelings and the causes of their differences with each other, in order to give some account of such differences and have done with it, they attribute them to chance, to some je ne sais quoi, or to pure caprice, thus confounding taste with fancy. However, we ought to avoid equally both confusion and excess."

– Jean-Pierre de Crousaz, Treatise on Beauty (1714), translated by Katerina Deligiorgi