|

| Alonso Berruguete Figure bearing Burden ca. 1510-15 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Baccio Bandinelli Figure Study ca. 1515-20 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola) Study for Executioner ca. 1526-28 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Francesco Granacci Study for St Sebastian before 1543 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Michelangelo Buonarroti Study of Left Leg ca. 1540-50 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Girolamo da Carpi Study of Draped Antique Statue before 1556 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| School of Fontainebleau Antique Statue of Bacchus 16th century drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Toussaint Dubreuil Figure Study ca. 1580-1600 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Bartolomeo Passarotti Figure Study before 1592 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Annibale Carracci Dancing Faun ca. 1597-1602 drawing (study for fresco, Galleria Farnese, Rome) Musée du Louvre |

|

| Peter Paul Rubens after Annibale Carracci Figure Study ca. 1601-1608 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

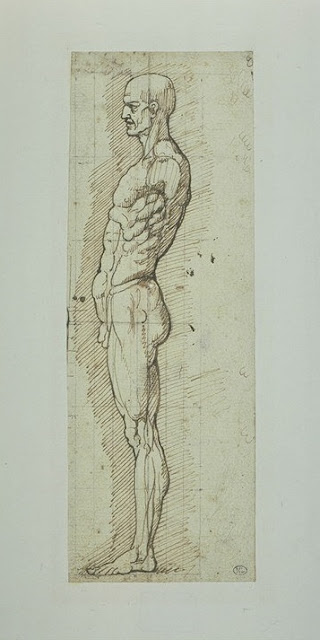

| Enea Salmeggia Anatomical Study before 1626 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Palma il Giovane Study of Suspended Figure before 1628 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Eustache Le Sueur Study for a Term ca. 1645-48 drawing (study for fresco cycle, The Life of St Bruno) Musée du Louvre |

|

| Eustache Le Sueur Study for a Term ca. 1645-48 drawing (study for fresco cycle, The Life of St Bruno) Musée du Louvre |

|

| Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié Académie before 1784 drawing Musée du Louvre |

"Our sight is the most perfect and most delightful of all our senses. It fills the mind with the largest variety of ideas, converses with its objects at the greatest distance, and continues the longest in action without being tired or satiated with its proper enjoyments. The sense of feeling can indeed give us a notion of extension, shape, and all other ideas that enter at the eye, except colours; but at the same time it is very much straitened, and confined in its operations to the number, bulk, and distance of its particular objects. Our sight seems designed to supply all these defects, and may be considered as a more delicate and diffusive kind of touch, that spreads itself over an infinite multitude of bodies, comprehends the largest figures, and brings into our reach some of the most remote parts of the universe."

"There are indeed but very few who know how to be idle and innocent, or have a relish of any pleasures that are not criminal; every diversion they take is at the expense of some one virtue or another, and their very first step out of business is into vice or folly. A man should endeavour, therefore, to make the sphere of his innocent pleasures as wide as possible, that he may retire into them with safety, and find in them such a satisfaction as a wise man would not blush to take. Of this nature are those of the imagination, which do not require such a bent of thought as is necessary to our more serious employments, nor, at the same time, suffer the mind to sink into that negligence and remissness, which are apt to accompany our more sensual delights, but, like a gentle exercise to the faculties, awaken them from sloth and idleness, without putting them upon any labour or difficulty."

– Joseph Addison, The Pleasures of the Imagination (1712)