|

| Henri de Braekeleer Man at a Window ca. 1873-76 oil on canvas Musée Fin-de-Siècle, Brussels |

|

| Henri de Braekeleer Flemish Kitchen Garden (La Coupeuse de Choux) ca. 1864 oil on canvas Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Henri Evenepoel Studio Interior 1897 oil on canvas Musée Fin-de-Siècle, Brussels |

|

| Jean de la Hoese The Model (lay figure in chair) ca. 1880 oil on canvas Musée d'Ixelles, Brussels |

|

| Fernand Khnopff A Blue Wing 1894 oil on panel Musée Fin-de-Siècle, Brussels |

|

| Fernand Khnopff The Garden ca. 1886 oil on canvas Musée Fin-de-Siècle, Brussels |

|

| Fernand Khnopff Portrait of the artist's sister, Marguerite 1887 oil on canvas, mounted on panel Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels |

|

| Jan van Beers Rendez-vous in the Bois de Boulogne 1889 oil on panel private collection |

|

| Jan Verhas The Reviewing of Schools ca. 1878 oil on canvas Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels |

|

| Charles van Beveren The Duet ca. 1830-50 oil on panel Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

| Charles van Beveren Portrait of sculptor Louis Royer 1830 oil on panel Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

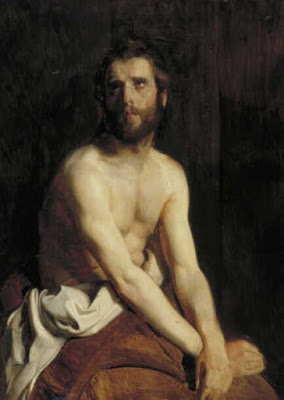

| Charles van Beveren Ecce Homo before 1850 oil on canvas Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam |

|

| Mathieu Ignace van Brée Self Portrait ca. 1820 oil on panel Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

| Mathieu Ignace van Brée Victims chosen for the Minotaur ca. 1815 oil on canvas Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels |

|

| Balthazar François Tasson-Snel Hercules 1830 oil on canvas Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels |

|

| Edgard Farasyn The Cheat (genre scene in the manner of the 17th century) 1878 oil on canvas Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool |

Margaret

I remember she rented a room on the second floor from Jenny Holtzerman, an Austrian widow. The two women lived on Girard Avenue South, in Kenwood, an elegant suburb of Minneapolis. Any promise of husbands had disappeared long ago. From the kitchen I often remember the jelly smell of a linzer torte. I was in high school and often I eavesdropped. Once, quietly, she said to my mother, "I never knew the love of a man." She had mentioned having a husband, but during the war they were separated in the chaos of Budapest, and later she lost track of him. Once she showed me her room: the walls were bare with cracks. Her daybed was narrow, barely slept-in. Her room resembled hundreds of scant little rooms around the world, the way it accepted blue and purple-violet detail – on her bureau, no family photographs, instead, playbills autographed by cast members, a calendar tattered, crossed, marked, no jewelry, some coins. Her window sashes warped, her wires shorted and the paint around her doorframe kept chipping off – "like in The Cherry Orchard," she said, "by Chekhov." She told a joke in Hungarian to Hannah Tamasek and even I, not knowing a word, laughed. She bowed gently in a mannerism distinctly Viennese and spoke on occasion of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. She loved the Guthrie Theater, where curtains rose on miniature worlds, preferring memorized dialogue and costumes to something truer. Five feet tall in orthopedic shoes, she limped. Time has a way of rearranging things and I could have most details wrong now, but there was this: during the war, she met a man, whom she gave money to, she did not know the man well, but had trusted him to smuggle her father across the border, the man pocketed the money, bought chocolates for his mistress from Belgium, and placed Margaret's father on a train to Auschwitz. So it makes sense to me now that when news reached us of Primo Levi's suicide, Margaret did not blink. It makes sense to me now that when Dr. Sikorski spoke of fighting in the Warsaw sewers, Margaret said, "I do not believe in God." Those who saw what they saw grow fewer. Margaret has been dead a long time now. But perhaps you will understand why I chose her, why I have smudged the slow waltz of her smile and added only a few modest blue strokes – here and here. As you leave Margaret behind and turn the page, listen as the page falls back and your hand gently buries her. This is what the past sounds like.

– Spencer Reece (2010)