|

| Joseph Boze Self Portrait ca. 1785 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| Joseph Boze Portrait of Jeanne Louise Henriette Campan, née Genet 1786 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

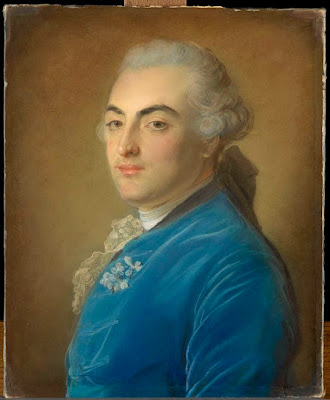

| Jean-Baptiste Perronneau Portrait of Jean Couturier de Flotte 1756 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| Rosalba Carriera Portrait of Anne Henry, épouse de Jacques-Vincent Languet de Gergy ca. 1720 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| Maurice Quentin de La Tour Self Portrait ca. 1755-60 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| Maurice Quentin de La Tour Portrait of Madame Louise as a Carmelite (daughter of Louis XV) ca. 1775 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| Maurice Quentin de La Tour Portrait of sculptor René Frémin ca. 1743 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jean-Étienne Liotard Portrait of Madame Jean Tronchin 1758 pastel on vellum Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jean-Marc Nattier Portrait of a Young Woman 1744 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| John Russell Portrait of Mrs Thomas Jeans and her Sons 1797 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| John Russell Portrait of painter Francesco Bartolozzi 1789 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun Portrait of a Young Man ca. 1792-95 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jean Valade Portrait of Théodore Lacroix 1774 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| Jean Valade Portrait of Madame Théodore Lacroix with her Daughter 1775 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| Claude Bornet Portrait of violinist Jacques Gosseaume 1763 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

|

| Claude Bornet Portrait of Madame Jean-Charles Gosseaume (mother of Jacques Gosseaume) 1763 pastel on paper Musée du Louvre |

"Everyone has a crayon in his hand – as with all that is fashionable, the public has embraced it with a frenzy," Étienne La Font de Saint-Yenne wrote in August 1746 in a review of the Salon paintings on display at the Musée du Louvre in Paris. Indeed, by the mid-eighteenth century pastel had reached an unprecedented level of acclaim as an artistic medium. It was appreciated for its stylistic diversity, the naturalism it evoked, its strength of color, and its suitability for informal portraits, the subject matter for which it was most frequently employed. Many material and practical factors also contributed to this resounding reception: the distinctive surface light and brilliant, nonyellowing colors of pastel portraits, the simplicity of the tools they required, the relative speed with which they could be executed, and their agreeable scale all underlay the ubiquitous demand for these likenesses. And each of these features was inseparably tied to the dustlike nature of pastel – powdered pigment formed into small sticks of opaque dry color – which in turn dictated the distinctive palette and techniques of the medium as well as the supports on which the fragile material was applied and the protection given its surface."

"That pastel flourished in the eighteenth century must be ascribed not only to its aesthetic desirability but to the emergence of a prosperous buying public, a cultural climate that encouraged technology and innovation, and a burgeoning trade in artists' materials, notably crayons, paper, glass, and fixatives. During the reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715) pastel had been employed for grand royal portraits, but in the early 1720s a shift occurred, sparked by the intimate crayon likenesses introduced by Rosalba Carriera during her brief sojourn in Paris in 1720-21. The smaller works Carriera inspired suited the taste and elegant decor of the new aristocracy."

"Perhaps the most fundamental material factor that accounted for the widespread popularity of portraits in pastel was the increased availability of ready-made crayons. As famed Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens noted in a letter of May 30, 1663, and French painter and theoretician Roger de Piles remarked in his Premiers éléments de la peinture pratique in 1684, it was possible to purchase ready-made crayons in the 1660s. Their commercial production was limited, however. By the early decades of the eighteenth century, trade in crayons had proliferated. As pastelists steadily gained in stature and dissociated themselves from the mechanical tasks of their métier, the fabrication of the colors, once carried out in the ateliers for the artists' own use, was handed over to independent artisans. Responding to both artists' and sitters' desire for portraits in pastel that emulated oil paintings, specialist pastel makers producing an ever broadening palette of crayons established themselves in cities across Europe."

"Advances in glass technology also helped fuel the demand for portraits in dry color. Although they were never executed on panel or directly on canvas, works in pastel were regarded as a type of painting. The need to protect these powdery surfaces, however, had limited their dimensions to the small size (rarely exceeding 29 by 17 inches) of the sheets cut from hand-blown crown glass. During the late 1680s a pouring process developed by the French royal glassworks (established in 1665 as one of the economic reforms of Louis XIV's minister of finance, Jean Baptiste Colbert) enabled the manufacture of clear cast plate glass measuring more than 60 by 40 inches, allowing pastel portraits to be executed on the same scale as those in oil. The luxury implied by the costly glazing made pastels viable alternatives to easel paintings and well suited to display the wealth and prestige of their owners."

– Marjorie Shelley, from an essay in Pastel Portraits: Images of 18th-Century Europe (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011)