|

| Francesco Marmitta Adoration of the Shepherds ca. 1500 tempera on vellum Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Benedetto Rusconi (il Diana) Virgin and Child with St John the Baptist ca. 1510-20 oil on canvas Pinacoteca Egidio Martini, Ca' Rezzonico, Venice |

|

| workshop of Jan van Scorel Baptism of Christ ca. 1550 oil on panel Indianapolis Museum of Art |

|

| Domenico Fetti Eve Spinning and Adam Laboring before 1623 oil on canvas Musée du Louvre |

|

| Herman van Swanevelt Landscape with David and Abigail ca. 1630 drawing (modello for lost painting) Musée du Louvre |

|

| Cornelis van Poelenburgh Women bathing in a Landscape 1630 oil on canvas National Gallery, London |

|

| Michel Corneille the Younger Group of Figures at a Fountain ca. 1660-70 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| attributed to Adriaen van Diest Buckingham House ca. 1703-1710 oil on canvas Royal Collection, Great Britain |

|

| Antonio Calza Episode from the Battle of Belgrade ca. 1717 oil on canvas private collection |

|

| Nicola Bertuzzi (also called Niccolò Bertucci or l'Anconitano) Passage of an Army over a Bridge ca. 1750-70 oil on canvas Pinacoteca Civica di Forlì |

|

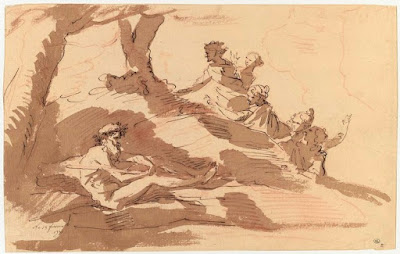

| Louis-Claude Vassé Mythological Scene 1771 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Louis-Claude Vassé Mythological Scene before 1772 drawing Musée du Louvre |

|

| Hubert Robert Fountain and Ruinous Colonnade in a Park 1775 oil on canvas Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels |

|

| Benjamin West Woodcutters in Windsor Park 1795 oil on canvas Indianapolis Museum of Art |

|

| Henri Fantin-Latour Alberich and the Rhine Maidens (scene from Das Rheingold by Wagner) 1876 colored chalks on paper Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

|

| Henri Rousseau War 1894 oil on canvas Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

"'Whoever cannot be an artist, should paint landscapes, fruit or flowers: it is always better to do something rather than nothing,' concluded Milizia in his article Landscape [in the Dizionario delle belle arti del disegno, 1797]. With these words he no doubt intended to signify that he did not hold in very high esteem the ability to excel in the art of painting landscapes. It seems to me that teachers of landscape painting do indeed overly exaggerate the difficulty of their art, placing landscape painting almost on the same rank as the highest genre of painting. If you listen to them, you will hear how much importance they attach to their clear skies, to the freshness and naturalness of the foliage on their trees, and to the depiction of water through confident strokes of the paintbrush. They say that to reach perfection in such things it is necessary to possess an exquisite understanding of the real world, a fecund imagination and the ability to enjoy the music of colour with one's eyes. I accept that there are difficulties, and that these are indeed numerous, because it is always difficult to do something well. However, even if exceptional skill is required to become a good landscape painter, much less is required than to become a history painter. Thus it is that when a history painter wishes to paint a landscape the way lies open in front of him, for he has but to look at the countryside to ensure that he will render it successfully. This is perfectly natural, since someone who can represent man and his passions accurately possesses many more skills than are needed to represent trees, houses and streams in a pleasing manner. However, it is not true, as many believe, that the possession of these skills enables the history painter to dispense with the study from real life of those objects in the countryside which he might wish to put in the background of his paintings. Woe to the many painters who live in this state of arrogant credulity; for they will only be able to offer us landscapes which are completely indeterminate or utterly false."

– Pietro Selvatico, from On the Education of the History Painter in Contemporary Italy (1842), translated by Olivia Dawson and Jason Gaiger (1998)