|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti Elizabeth Siddall reading 1854 drawing Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge |

"Elizabeth Siddall is known today as the woman who lay in the bath to model for Millais's Ophelia, and for her brief, tragic marriage to Rossetti, culminating in death from an overdose of laudanum, and the subsequent exhumation of her body by her husband to recover his love poems. Yet, unusual among the train of attractive young models who posed for the Pre-Raphaelites, Elizabeth Siddal had, herself, ambitions to be an artist and a poet, goals which, despite obstacles, she to some extent achieved. Professional modelling occupied only two years of Elizabeth Siddal's life. She was among the first in a series of young women to have attracted the collective attention of the Pre-Raphaelites as model and muse. Yet she, more than any other of the 'stunners' picked out by the Brotherhood, suffered for their art – not so much physically, or even emotionally, but by the suppression of her own character and achievements."

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti Study for Found (Fanny Cornforth) 1858 drawing Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, West Midlands |

"Rossetti's 'town subject' or Found occupied the artist intermittently for over twenty-five years, although it was never finished. The painting, begun in 1854, depicts the discovery of a 'fallen' woman by a young drover on his way to market with a calf, who realises that the slumped body of the prostitute is that of his former sweetheart. According to Fanny Cornforth, who had apparently been working as a prostitute (and who also claimed to be a farmer's daughter) the study for Found was made by Rossetti when he first took her to his studio, 'where he put my head against the wall and drew it for the head in the calf picture."

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti Annie Miller 1860 drawing private collection, on loan to Manchester Art Gallery |

"Annie Miller was the archetypal Pre-Raphaelite 'stunner' – beautiful, promiscuous, and working-class. When discovered at the age of fifteen by William Holman Hunt, Annie was already working part-time as an artist's model. She was born in 1835, the youngest of three children of a Chelsea pensioner and veteran of the Napoleonic Wars. When Hunt found her, Annie was working as a barmaid and living in semi-squalor behind the Cross Keys pub in Chelsea. Hunt, enamoured of her good looks and vivacity, paid for her education, including lessons in deportment and etiquette. . . . In 1854 Hunt left for Syria. During his absence Annie modelled for Millais and for Rossetti, with whom she began an affair. By the mid-1850s she was very much in demand as a model – and a mistress – although Hunt continued to regard her as his particular possession. . . . In 1863 Annie married a cousin of Lord Ranelagh (with whom she had also had a protracted affair). Hunt recalled meeting her some years later on Richmond Hill, 'a buxom matron with a carriage full of children.' Annie's husband died in 1916 at the age of eighty-seven. She died in 1925, aged ninety, at Shoreham-by-Sea."

"Rossetti probably began an affair with Fanny Cornforth in 1863, shortly after the death of his wife Elizabeth Siddall, and the year in which he painted Fazio's Mistress, an illustration of verses by Fazio degli Uberti (1325-1360) which Rossetti had translated into English in 1861. . . . Although Fanny remained with Rossetti, by the early 1870s he had come to regard her more as a housekeeper than muse or mistress, distancing himself from her socially, while offering financial support. In 1873 Rossetti partly repainted Fazio's Mistress, although he reassured Fanny, 'I am not working at all on the head, which is exactly like the funny old elephant, as like as any I ever did.' Fanny remained loyal to Rossetti until his death in 1881, although his family prevented her from attending his funeral."

"It has been observed that the real-life identities of Julia Margaret Cameron's models do not matter, since they do not impart meaning to images which 'find their meaning in the space between idealist fiction and realist fact.' Yet Cameron's photographs, unlike the Pre-Raphaelite paintings which they recall, evoke the real physical presence of the living model far more graphically than the imaginary characters they purport to represent. Indeed, Mary Hillier, who featured as the Madonna in countless photographs, became known locally under her alter ego, 'The Island Madonna.'

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti Aurelia - Fazio's Mistress (Fanny Cornforth) 1863 oil on panel Tate Britain |

"Rossetti probably began an affair with Fanny Cornforth in 1863, shortly after the death of his wife Elizabeth Siddall, and the year in which he painted Fazio's Mistress, an illustration of verses by Fazio degli Uberti (1325-1360) which Rossetti had translated into English in 1861. . . . Although Fanny remained with Rossetti, by the early 1870s he had come to regard her more as a housekeeper than muse or mistress, distancing himself from her socially, while offering financial support. In 1873 Rossetti partly repainted Fazio's Mistress, although he reassured Fanny, 'I am not working at all on the head, which is exactly like the funny old elephant, as like as any I ever did.' Fanny remained loyal to Rossetti until his death in 1881, although his family prevented her from attending his funeral."

|

| Julia Margaret Cameron Call, I Follow (Mary Hillier) 1867 carbon print Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

"It has been observed that the real-life identities of Julia Margaret Cameron's models do not matter, since they do not impart meaning to images which 'find their meaning in the space between idealist fiction and realist fact.' Yet Cameron's photographs, unlike the Pre-Raphaelite paintings which they recall, evoke the real physical presence of the living model far more graphically than the imaginary characters they purport to represent. Indeed, Mary Hillier, who featured as the Madonna in countless photographs, became known locally under her alter ego, 'The Island Madonna.'

|

| John Gilbert Rembrandt's Studio 1869 oil on canvas York City Art Gallery |

|

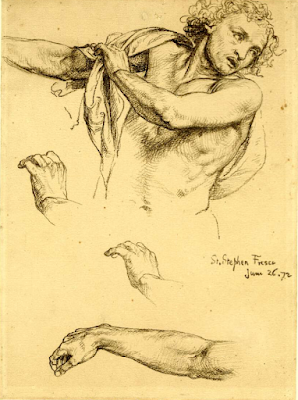

| Edward Poynter Figure Studies 1872 drawing (study for fresco, Martyrdom of St Stephen) British Museum |

"Poynter's figure study, possibly based on an Italian model, was one of a series of drawings made for a fresco cycle in St Stephen's, Dulwich, shortly after his appointment as first Professor at the Slade School of Art in 1871. Here it acts as a paradigm of the drawing style he wished to promote through his pedagogy. In his inaugural lecture to Slade students Poynter stated that the school was to be based on the French atelier system, where speed of execution and fluent draughtsmanship were valued above minute attention to detail."

|

| Edward Poynter Figure and Anatomical Studies 1872 drawing (study for fresco, Martyrdom of St Stephen) British Museum |

|

| Edward Poynter Figure Studies ca. 1876 drawing (study for painting, Atalanta's Race) British Museum |

|

| Edward Burne-Jones Study of Mary Zambaco 1871 drawing private collection |

"By 1869 Burne-Jones was so captivated by Mary Zambaco (his 'sweet Owl') that he contemplated deserting his wife, Georgiana. When he abandoned the idea, Mary made several very public suicide attempts, including a plunge into the Regent's Canal in Maida Vale. Despite their temporary estrangement, Burne-Jones continued to use her as his model and muse over the next few years (much to the distress of his wife). . . . Unlike so many of the beautiful young women pursued by the Pre-Raphaelites, Mary Zambaco was not poor or dependent on their collective largesse. The granddaughter of a wealthy Greek businessman, Mary had inherited a fortune at the age of fifteen on the death of her father. Although from a solidly middle-class background, she was wholly unconcerned with convention."

|

| Edward Burne-Jones Pygmalion and Galatea: The Soul Attains 1878 oil on canvas Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery |

"The wish-fulfillment behind this constructed female ideal can also be seen in many of the myths depicted by the Pre-Raphaelites and their circle. The most telling of these is the Greek myth of Pygmalion, in which the statue of a beautiful woman comes to life. The theme might seem to represent the apotheosis of the model. But it is worth reflecting that it actually shows the reverse of the process practised by the Pre-Raphaelites. For in the Pygmalion myth the work of art becomes a person, whereas for them it was the person who was transformed into the work of art. Yet no matter which way the process was working, in both cases it assumed a necessary link between the persona of the model and that of the image."

|

| Samuel Butler Mr Heatherley's Holiday: an Incident in Studio Life 1874 oil on canvas Tate Britain |

"Thomas J. Heatherley (1826-1914) became principal of Leigh's Art School in 1860, following the death of the founder, James Matthews Leigh. . . . Although Heatherley changed the name of the school to reflect his proprietorial status, the same relaxed, if doctrinaire, atmosphere was maintained. Over the years Heatherley continued to accumulate a huge collection of artistic props: suits of armour, skeletons, historical costumes, stuffed animals and pottery. Many of these were housed in his Antique Room, alongside the cast collection. . . . Samuel Butler initially saw Heatherley's School as a stepping stone towards entry to the Royal Academy Schools, but quickly came to distrust what he saw as the dead hand of current academic training. . . . The academy is here characterised as a fusty lumber room, the vital presence of the living model supplanted by a skeleton caressed by a grey-haired old man."

|

| Thomas Cooper Gotch Head and Shoulders of Model ca. 1875 drawing British Museum |

|

| Thomas Wilson Standing Model 1877 oil on canvas Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture |

|

| Joseph Benwell Clark Recumbent Model 1878 etching British Museum |

|

| John Tenniel Pygmalion and the Statue 1878 watercolor on paper Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

"Tenniel's Pygmalion derived from an early drawing for Clytie in the Historical Ballads. He chose to revise it at a time when the Victorian obsession with the story was at its peak, during the 1870s and 1880s. The story of Pygmalion was told in Book X of Ovid's Metamorphoses. Revolted 'by the many faults which nature has implanted in the female sex,' Pygmalion of Paphos shunned the company of women, and instead fashioned an ivory statue with which he fell in love. . . . The potential of the Pygmalion myth as a paradigm for the artist-model relationship was exploited most thoroughly by British artists at a time when questions were being asked about the necessity of the female nude to the creative process, although the fact that Pygmalion was driven to create the ideal woman because of his own misogyny appears to have been ignored."

– quoted passages from The Artist's Model from Etty to Spencer by Martin Postle and William Vaughan (London: Merrell Holberton, 1999)