|

| Hans Wechtlin Pyramus and Thisbe (episode in Ovid's Metamorphoses) ca. 1510 chiaroscuro woodcut Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio |

|

| Paolo Veronese Leda and the Swan (episode in Ovid's Metamorphoses) ca. 1575 oil on canvas Musée Fesch, Ajaccio, Corsica |

-c1620-21-oil-on-canvas-Alte-Pinakothek-Munich.jpg) |

| Jacob Jordaens The Satyr and the Peasant (fable of Aesop) ca. 1620-21 oil on canvas Alte Pinakothek, Munich |

-1773-oil-on-canvas-Los-Angeles-County-Museum-of-Art.jpg) |

| Benjamin West Cymon and Iphigenia (episode in Boccaccio's Decameron) 1773 oil on canvas Los Angeles County Museum of Art |

-c1782-84-oil-on-canvas-National-Gallery-of-Art-Washington-DC.jpg) |

| Joseph Wright of Derby The Corinthian Maid (legend from Pliny the Elder about the invention of drawing) ca. 1782-84 oil on canvas National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

-1786-oil-on-canvas-Ch%C3%A2teau-de-Versailles.jpg) |

| Jean-Baptiste Regnault The Origin of Painting (the Corinthian Maid legend from Pliny the Elder) 1786 oil on canvas Château de Versailles |

|

| Tommaso Conca The poet Homer with the Muse Calliope ca. 1786 drawing National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

-1787-oil-on-canvas-National-Gallery-of-Norway-Oslo.jpg) |

| Nicolai Abildgaard Richard III (scene from Shakespeare) 1787 oil on canvas National Gallery of Norway, Oslo |

-c1792-1802-oil-on-canvas-Neue-Pinakothek-Munich.jpg) |

| Henry Fuseli Satan encounters Death and Sin at the Gates of Eden (scene from Milton's Paradise Lost) ca. 1792-1802 oil on canvas Neue Pinakothek, Munich |

|

| Nicolai Abildgaard Greek poet Anacreon and his beloved Bathyllus ca. 1808 oil on canvas Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen |

-Scottish-National-Gallery-Edinburgh.jpg) |

| William Ewart Lockhart Gil Blas and the Archbishop (scene from novel by Alain-René Lesage) ca. 1880 drawing Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh |

|

| Edvard Munch Portrait of writer Hans Jæger 1889 oil on canvas National Gallery of Norway, Oslo |

|

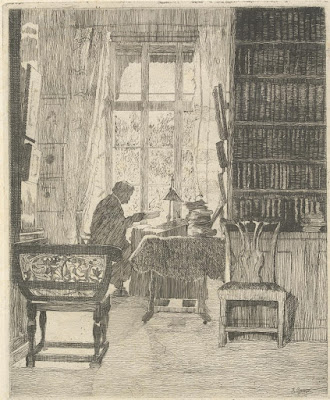

| Sylvia Gosse The author Edmund Gosse in his Study ca. 1913 etching National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne |

|

| James A.S. Torrance Tammie felt the wind of Nuckelavee's clutch (illustration to Scottish Fairy and Folk Tales) ca. 1900 gouache on paper Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh |

-Shipwreck-1949-gouache-on-paper-National-Gallery-of-Victoria-Melbourne.jpg) |

| Danila Vassilieff Fairytale Study - Shipwreck 1949 gouache on paper National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne |

Le Musée Imaginaire

An Aztec sacrifice,

beside the head of Pope:

eclectic and unresolvable.

We admire the first

for its expressiveness, the second

because we understand it –

can re-create

its circumstances, and share

(if not the presuppositions)

the aura

of the civilities surrounding it.

The other, in point

at any rate, of violence

touches us more nearly.

And yet . . . it is cruel

but unaccountably so; for the temper of awe

demanded by the occasion, escapes us:

it is not

better than we are –

it is merely different.

Expressive, certainly. But of what?

Our loss is absolute, yet unfelt

because inexact. The head

of Alexander Pope,

stiller, attests the more tragic lack

by remaining

what it was meant to be;

We admire the first

for its expressiveness, the second

because we understand it –

can re-create

its circumstances, and share

(if not the presuppositions)

the aura

of the civilities surrounding it.

The other, in point

at any rate, of violence

touches us more nearly.

And yet . . . it is cruel

but unaccountably so; for the temper of awe

demanded by the occasion, escapes us:

it is not

better than we are –

it is merely different.

Expressive, certainly. But of what?

Our loss is absolute, yet unfelt

because inexact. The head

of Alexander Pope,

stiller, attests the more tragic lack

by remaining

what it was meant to be;

intelligible,

it forbids us to approach it.

– Charles Tomlinson (1963)