|

| Lynne Cohen Furniture Showroom 1979 gelatin silver print Tate Gallery, London |

|

| Marketa Luskacova Woman and Man with Bread, Spitalfields, London 1976 gelatin silver print Tate Gallery, London |

|

| Jonas Dovydenas Adolescent, Manchester, Kentucky 1971 gelatin silver print Minneapolis Institute of Art |

|

| Guy Bourdin Untitled 1952 gelatin silver print Tate Gallery, London |

|

| Iwao Yamawaki Cafeteria after Lunch, Bauhaus, Dessau ca. 1930-32 gelatin silver print Tate Gallery, London |

1. Photography is, first of all, a way of seeing. It is not seeing itself.

2. It is the ineluctably "modern" way of seeing – prejudiced in favor of projects of discovery and innovation.

|

| Yva (Else Simon) Dance ca. 1933 photogravure private collection |

|

| Edvard Munch Self-portrait “à la Marat” 1908-1909 photograph Munch Museum, Oslo |

|

| Samuel Joshua Beckett Loїe Fuller Dancing ca. 1900 gelatin silver print Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Arnold Genthe Merchant and Body Guard, Old Chinatown, San Francisco ca. 1896-1906 gelatin silver print San Francisco Museum of Modern Art |

|

| Adrien Constant de Rebecque Man posed as Dying Soldier ca. 1863 albumen print Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

6. In the modern way of knowing, there have to be images for something to become "real." Photographs identify events. Photographs confer importance on events and make them memorable. For a war, an atrocity, a pandemic, a so-called natural disaster to become a subject of large concern, it has to reach people through the various systems (from television and the internet to newspapers and magazines) that diffuse photographic images to millions.

7. In the modern way of seeing, reality is first of all appearance – which is always changing. A photograph records appearance. The record of photography is the record of change, of the destruction of the past. Being modern (and if we have the habit of looking at photographs, we are by definition modern), we understand all identities to be constructions. The only irrefutable reality – and our best clue to identity – is how people appear.

|

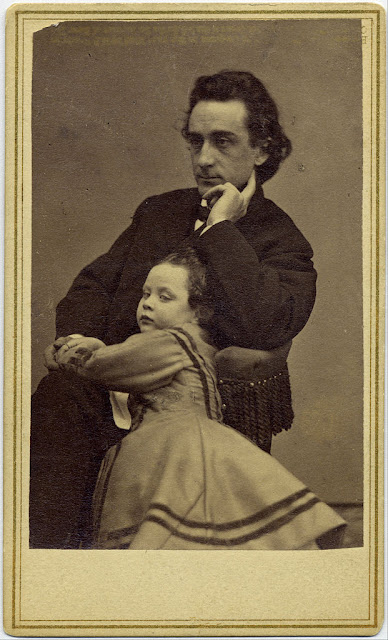

| Mathew Brady Portrait of Edwin Booth and his daughter Edwina ca. 1863-65 albumen print George Eastman House, Rochester NY |

|

| Lady Clementina Hawarden Poodle on Chairs 1861 albumen print Victoria & Albert Museum |

|

| Horatio Ross Tree ca. 1858 albumen silver print Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Roger Fenton Billiard Room at Mentmore ca. 1858 albumen silver print Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

|

| John Adams Whipple and James Wallace Black The Moon ca. 1857-60 salted paper print Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

10. To know is, first of all, to acknowledge. Recognition is the form of knowledge that is now identified with art. The photographs of the terrible cruelties and injustices that afflict most people in the world seem to be telling us – we who are privileged and relatively safe – that we should be aroused; that we should want something done to stop these horrors. And then there are photographs that seem to invite a different kind of attention. For this ongoing body of work, photography is not a species of social or moral agitation, meant to prod us to feel and to act, but an enterprise of notation. We watch, we take note, we acknowledge. This is a cooler way of looking. This is the way of looking we identify as art.

11. The work of some of the best socially engaged photographers is often reproached if it seems too much like art. And photography understood as art may incur a parallel reproach – that it deadens concern. It shows us events and situations and conflicts that we might deplore, and asks us to be detached. It may show us something truly horrifying and be a test of what we can bear to look at and are supposed to accept. Or often – this is true of a good deal of the most brilliant contemporary photography – it simply invites us to stare at banality. To stare at banality and also to relish it, drawing on the very developed habits of irony that are affirmed by the surreal juxtapositions of photographs typical of sophisticated exhibitions and books.

|

| Louis-Antoine Froissart Flood in Lyon 1856 albumen silver print Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

|

| Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes Nude artist's model ca. 1856-59 salted paper print Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Mervyn Herbert Nevil Story Maskelyne Charlton House, Malmesbury, Wiltshire 1856 salted paper print Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

| Louis-Adolphe Humbert de Molard Louis Dodier as a Prisoner 1847 daguerreotype Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

|

| Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey Ancient Columns early 1840s daguerreotype Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

– text by Susan Sontag, from Photography: A Little Summa (2003)