|

| Anonymous artist Moses and the Brazen Serpent 17th century oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|

| Claude Vignon Moses with the Tablets of the Law before 1670 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|

| Jürgen Ovens Jacob wrestling with the Angel before 1678 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

"At the beginning of the modern era, in Ignatius's century, one fact seems to begin to modify the exercise of the imagination: a reordering of the hierarchy of the five senses. In the Middle Ages, historians tell us, the most refined sense, the perceptive sense par excellence, the one that established the richest contact with the world, was hearing: sight came in only third place, after touch. Then we have a reversal: the eye becomes the prime organ of perception (Baroque, art of the thing seen, attests to it). This change is of great religious importance. The primacy of hearing, still very prevalent in the sixteenth century, was theologically guaranteed: the Church bases its authority on the word, faith is hearing, auditum verbi Dei, id est fidem; the ear, the ear alone, Luther said, is the Christian organ. Thus a risk of contradiction arises between the new perception, led by sight, and the ancient faith based on hearing. Ignatius set out, as a matter of fact, to resolve it: he attempts to situate the image (or interior "sight") in orthodoxy, as a new unit of the language he is constructing."

"Yet there are religious oppositions to the image (aside from the auditory mark of faith, received, upheld, and reaffirmed by the Reformation). The first are ascetic in origin: sight, the procuress of touch, is easily associated with desire of the flesh (although the antique myth of seduction was that of the Sirens, i.e., melodic temptation), and the ascetic shunned it all the more so in that it is impossible to live without seeing; further, one of the predecessors of John of the Cross imposed a five-foot limit on his visual perception, beyond which he was not to look. Anterior to language ("Before language," Bonald says, "there was nothing but bodies and their images"), the image was thought to represent something barbaric and, in a word, "natural," which rendered it suspect to any disciplinary morality. Perhaps this mistrust vis-à-vis the image represents the presentiment that sight is closer to the unconscious and all that animates it, as Freud has noted."

– Roland Barthes, from Sade / Fourier / Loyola, translated by Richard Miller (New York: Hill and Wang, 1976) – a briefer excerpt from this same crucial passage was previously quoted here

|

| Leandro Bassano St Anne with the Virgin as a child ca. 1620 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|

| Matthias Stom Adoration of the Magi ca. 1630-35 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|

| Jacob Jordaens Adoration of the Shepherds 1618 oil on panel Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|

| Michael Dahl The Holy Family 1691 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

"The Church developed additional, more ambiguous oppositions to the image: those of the mystics. Commonly, images (particularly visions and, with greater reason, "sight," of an inferior order) are not admitted in mystical experience save in a preparatory role: they are exercises for debutants; for John of the Cross, images, forms and meditations are suitable only for beginners. The goal of the experience is, on the contrary, the deprivation of images; it is "to mount with Jesus to the summit of our spirit, on the mountain of Nakedness, without image" (Ruysbroeck). John of the Cross notes that the soul "in an act of confused, amorous, peaceful, and fulfilled ideation" (successful in relinquishing distinct images) cannot without painful fatigue return to particular contemplations, in which one discourses in images and forms; and Theresa of Avila, although in this respect she occupies an intermediate position between John of the Cross and Ignatius Loyola, keeps aloof when it comes to the imagination: "So inert is this faculty in me that despite all my efforts I can never picture or represent to myself the Holy Humanity of our Lord" (a representation which Ignatius, as we have seen, incessantly provokes, varies, and exploits). It is well known that from a mystical viewpoint, abyssal faith is dark, submerged, flowing (says Ruysbroeck) in the immense shadow of God Who is the "face of sublime nothingness," – meditations, contemplations, visions, sights, and discourses, in short, images, occupying only the "spirit's husk."

– Roland Barthes, from Sade / Fourier / Loyola, translated by Richard Miller (New York: Hill and Wang, 1976)

|

| Jacob Adriaensz Backer The Tribute Money ca. 1630-40 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|

| Willem van Herp Entry into Jerusalem before 1677 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|

| Pierre-Louis Cretey St Mark the Evangelist before 1691 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|

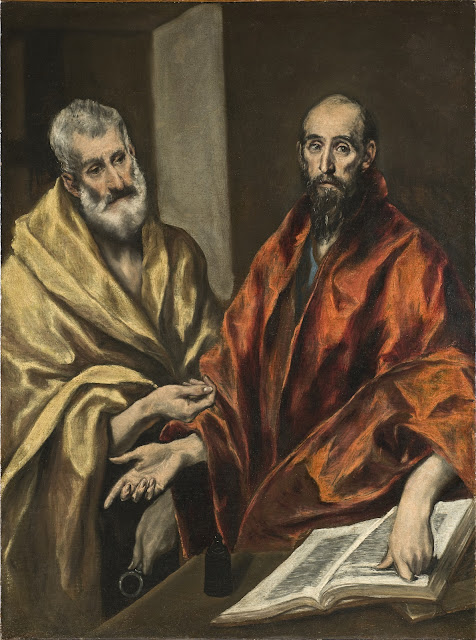

| El Greco St Peter and St Paul before 1614 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

"The Exercises can be conceived as a desperate struggle against the dispersal of images which psychologically, they say, marks mental experience and over which – every religion agrees – only an extremely rigorous method can triumph. Ignatian imagination, as has been stated, has first this function of selection and concentration: it is a matter of casting out these fleeting images that invade the spirit like "a disorderly swarm of flies" (Theophanes the Hermit) or "capricious monkeys leaping from branch to branch" (Ramakrishna); but to substitute what for them? In fact, it is not against the proliferation of images that the Exercises is finally struggling, but, far more dramatically, against their inexistence, as though, originally emptied of fantasms, the exercitant (whatever the disposition of his spirit) needed assistance in providing himself with them. It can be said that Ignatius takes as much trouble filling the spirit with images as the mystics (Christians and Buddhists) do in emptying them out; and if we turn to certain present-day hypotheses, which define the psychosomatic patient as a subject powerless to produce fantasies and his cure as a methodical effort to bring him to a "capacity for fantasy manipulation," Ignatius is then a psychotherapist attempting at all costs to inject images into the dull, dry and empty spirit of the exercitant, to introduce into him the culture of fantasy, preferable despite the risks to that fundamental nothingness (nothing to say, to think, to imagine, to feel, to believe) which marks the subject of speech before the rhetors or the Jesuits bring their technique to bear and give it a language."

– Roland Barthes, from Sade / Fourier / Loyola, translated by Richard Miller (New York: Hill and Wang, 1976)

|

| Jan Lievens Apostle Paul ca. 1627-29 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|

| Claude Vignon Vision of St Jerome 1626 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|

| Philippe de Champaigne St Bruno 1655 oil on canvas Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |

|

| Anonymous artist The Eucharist 1660 oil on canvas, mounted on panel Nationalmuseum, Stockholm |